Action Scenes in 1990s Bond Films: A Modest Reply to David Bordwell

In another fine blog post, David Bordwell contrasts two kinds of 1990s action scene, one apparently representative of James Bond films and the other of Hong Kong—in this case, Jackie Chan—films. As always, this entry pushes us to appreciate the art of filmmaking in new ways, asking us to consider the skill in Chan’s action scenes and the lack thereof in Bond’s.

In another fine blog post, David Bordwell contrasts two kinds of 1990s action scene, one apparently representative of James Bond films and the other of Hong Kong—in this case, Jackie Chan—films. As always, this entry pushes us to appreciate the art of filmmaking in new ways, asking us to consider the skill in Chan’s action scenes and the lack thereof in Bond’s.

But, as a Bond lover, I feel obligated to offer an objection or two, and to attempt to counter Bordwell’s analysis with one of my own. The point of engaging in this action-scene debate is not to argue that 1990s Bond trumps 1990s Hong Kong action. All I aim to show is how a defense of the artistry of Bond-style action might go—to defend an aspect of Bond that critics other than Bordwell now rather hastily caricature.

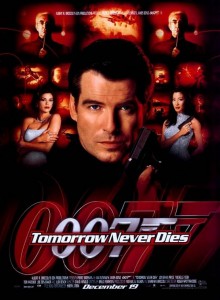

The premise of Bordwell’s analysis is that the action scene he’s selected from Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) is ho-hum and unclear in terms of the action depicted. I don’t have space to contest the first claim, but this much can be shown: the scene is perfectly clear, even efficient, in its action and storytelling.

The action appears unclear only if the scene is viewed in an acoustic vacuum. And that is not the assumption of the filmmakers. Sound is as much a part of their storytelling and action-sequence toolbox as cutting and staging. Here, director Roger Spottiswoode and his sound editors, Peter Bond and Peter Baldock, use sound efficiently to replace what would have been superfluous matter on the visual track. When the first security guard tackles Bond on the catwalk and chokes him on the edge, Bond retaliates with one slug…

… and then another.

A close-up shows that Bond is shocked that his nemesis hasn’t succumbed.

Still in the same shot, Bond winds up—we hear Brosnan’s voice ggrrmmm as he builds up strength—

…and he punches the henchman for a third time. Cut to the guard, who, as he lets go of Bond, is sent for a spin and drops below the frame.

Bordwell seems to suggest that when this happens, we lose our bearings on the action, because we don’t see the guard fall to the floor and roll out of sight. But we do hear him. The smack of the guard crumbling onto the catwalk is carefully cued just as he drops below the frame. This, combined with a shot of Bond looking down at his defeated opponent (with the second guard leaping into the scene from behind), confirms for us that henchman number one is down and out.

So, no real doubt remains about whether he’ll make a comeback.

This scene is a tidy example of efficiency of staging, editing and sound design in action cinema. French auteur Robert Bresson once shocked cinephiles by lauding the 1981 Bond film, For Your Eyes Only, as an example of le cinématographe. For Bresson, le cinématographe is a form of writing with the medium of film that is antithetical to the theatrical arts from which filmmakers tend to borrow, like staging. Bresson, an advocate of stylistic restraint, argued that if cinema is to distinguish itself as a unique art form, it must govern its theatrical excesses. One way to do this is to use the soundtrack to its full potential. He famously wrote in his 1975 book, Notes sur le cinématographe:

One does not create by adding, but by taking away.

Also:

The eye (in general) superficial, the ear profound and inventive. A locomotive’s whistle imprints in us a whole railroad station.

Finally:

When a sound can replace an image, cut the image or neutralize it. The ear goes more toward the within, the eye towards the outer.

Perhaps Bresson would have appreciated the visual economy on display in Roger Spottiswoode’s handling of action. The Tomorrow Never Dies director showed only what he needed to show, and where he could, he astutely replaced the visual depiction of an action—the guard hitting the floor—with a sound effect, thus trusting that the viewer would “complete” the action in her mind. He cleverly omitted a shot that, in retrospect, seems utterly unnecessary to create a clear sense of the ongoing action.

Not all action directors adhere to the school of thought that says that stimulating action consists of widely framed displays of virtuosic gymnastics. For some, tight, intense framings and strategically timed sound cues are more important.

For them, less is more.

The demands of narrative intelligibility do support your counter-argument. As long as information about the progression of a fight (or action sequence, if a broader term is necessary) is clearly communicated by whatever mode, visual or aural, the audience won’t be left behind.

As important as that is, though, one of the unique delights of action cinema–and films with fight scenes, in particular–is, in my opinion, the visceral sensation one experiences in the viewing (and the listening).

A locomotive’s whistle may call up the iconography of an entire railroad station, but a fist heard smashing into someone’s face isn’t exactly cringe-inducing. See it; feel it (where film fighting is concerned).

Leo, thank you for the thoughtful reply. Because we’re friends, I hope you’ll accept a brief, and somewhat cheeky, reply. (Readers: please don’t get the impression that I’m adverse to conversation. I simply value parsimony. Less is more, indeed.)

Leo: mute the volume while watching ANY action scene, and you’ll no doubt notice the fatal flaw in your “see it/feel it” position.

Your article constitutes an insightful addendum to Prof. Bordwell’s blog post. The parallels you draw to the critical theory of Robert Bresson are quite enlightening. Sound definitely forms an essential part of effective action cinema, particularly in the Bond universe. The economical use of sound design responds to the choreographic demands of the scene which basically translates as a barrage of physical attacks in a narrow, almost claustrophobic space. One could argue that director Roger Spottiswoode could have elected a different, wider camera angle to frame the action more intelligibly for general audiences. But, considering the restricted space of the scene, the catwalk, the fragmented close shots evoke an adequate atmosphere (and simultaneously relate the perception of the audience to the film’s narrative focus: Bond).

As you value succinctness, I apologize for the perhaps nonsensical, protracted response. But I find that Prof. Bordwell’s wonderful blog post (in which he sketches out the constituents of the action cinema I prefer)and your astute response warrant a longer text.