From Nottingham and Beyond: British Classical Music Radio, Public Service Broadcasting and the Neoliberal Market

Post by Roberta Pearson, Department of Culture, Film and Media, University of Nottingham

This is the first installment in what is intended to be a series of roughly fortnightly blogs under the rubric of “From Nottingham and Beyond.” The Department of Culture, Film and Media at the University of Nottingham in the UK and the Department of Communication Arts share common interests in media industries—a commonality signalled by Prof. Michele Hilmes’ stay with us last year as Nottingham’s first Fulbright Fellow. When Jonathan Gray suggested that we make a regular contribution to Antenna, we happily agreed, thinking that this would further strengthen the bonds between the two departments. We have assembled a group of contributors comprised of both academic staff at Nottingham and many of our recent alumni, working either in higher education or in the industry both in the UK and abroad.

These contributors have been asked to bring a UK and/or global perspective to their Antenna blogs. I’m going to kick off by writing about current developments in British classical music radio. The ongoing controversy over the current programming strategies of BBC Radio 3 the nation’s non-commercial classical music radio channel, speaks to broader debates concerning the purpose and future of public service broadcasting in the UK as well as to broader debates concerning the future of the arts. The national debate about the channel’s “dumbing down” in search of larger audiences has broader implications in an age in which the logics of an aggressive neoliberalism that elevates market competitiveness over all other measures of value threaten public service broadcasting in the UK, the rest of Europe and elsewhere.Classical music has had a dedicated radio channel in the UK since the establishment of the BBB’s Third Programme in 1946. In 1967, when the BBC launched its first pop music station, Radio 1, the Light Programme became Radio 2, the Home Programme Radio 4 and the Third Programme Radio 3. Neither the Third Programme nor Radio 3 intended to cater for a broad-based mass audience for classical music. Instead, both had reputations for being unabashedly elitist and rather terrifyingly cerebral, playing a defiantly non–crowd-pleasing repertoire that frequently included the atonal and the avant-garde. This was not a problem at a time when the BBC’s public service values represented a broad cultural consensus about the purpose and value of radio and television.

These contributors have been asked to bring a UK and/or global perspective to their Antenna blogs. I’m going to kick off by writing about current developments in British classical music radio. The ongoing controversy over the current programming strategies of BBC Radio 3 the nation’s non-commercial classical music radio channel, speaks to broader debates concerning the purpose and future of public service broadcasting in the UK as well as to broader debates concerning the future of the arts. The national debate about the channel’s “dumbing down” in search of larger audiences has broader implications in an age in which the logics of an aggressive neoliberalism that elevates market competitiveness over all other measures of value threaten public service broadcasting in the UK, the rest of Europe and elsewhere.Classical music has had a dedicated radio channel in the UK since the establishment of the BBB’s Third Programme in 1946. In 1967, when the BBC launched its first pop music station, Radio 1, the Light Programme became Radio 2, the Home Programme Radio 4 and the Third Programme Radio 3. Neither the Third Programme nor Radio 3 intended to cater for a broad-based mass audience for classical music. Instead, both had reputations for being unabashedly elitist and rather terrifyingly cerebral, playing a defiantly non–crowd-pleasing repertoire that frequently included the atonal and the avant-garde. This was not a problem at a time when the BBC’s public service values represented a broad cultural consensus about the purpose and value of radio and television.

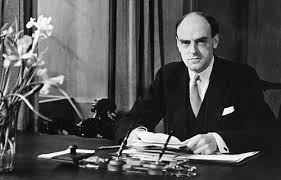

The BBC’s first Director General, John Reith (above), first articulated the fundamental principles of public service broadcasting and since then, as the BBC itself has said, the term “‘Reithian values’ has become a byword for public service broadcasting.” Central to those values was giving the audience what it needed rather than what it wanted – educating and uplifting rather than appealing to populist tastes or attempting to attract hordes of listeners and viewers. Funded by the license fee, the annual payment made by each household owning a radio and then a television, the BBC could program content that might not attract large audiences but that was nonetheless seen as providing value to the nation in terms of introducing audience members to cultural forms such as classical music that they might otherwise never encounter.

The BBC’s first Director General, John Reith (above), first articulated the fundamental principles of public service broadcasting and since then, as the BBC itself has said, the term “‘Reithian values’ has become a byword for public service broadcasting.” Central to those values was giving the audience what it needed rather than what it wanted – educating and uplifting rather than appealing to populist tastes or attempting to attract hordes of listeners and viewers. Funded by the license fee, the annual payment made by each household owning a radio and then a television, the BBC could program content that might not attract large audiences but that was nonetheless seen as providing value to the nation in terms of introducing audience members to cultural forms such as classical music that they might otherwise never encounter.

The 1992 launch of commercial classical music radio station Classic FM which has as its mission “to make classical music accessible and relevant to a modern audience through its engaging style” was a game-changer for Radio 3. Classic FM presented itself as a gateway to classical music, appealing to listeners whose lack of the requisite cultural capital frightened them off from the high-brow Radio 3. It enjoyed immediate success by exploiting the increasing popularity of the kind of ‘mainstream’ classical music – Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Pachelbel’s Canon and the like – that we are constantly exposed to when shopping, riding elevators, holding on customer service lines, overhearing mobile ringtones, walking through airports, boarding airplanes, eating in restaurants, going to the cinema and watching television.

The playlist is restricted, drawn from the limited mainstream repertoire, and repetitive, with certain compositions regularly featured – Schubert’s Trout Quintet, Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture or Rachmaninov’s 2nd Piano Concerto (images). Usually only the best-known movements are played rather than the entire work. And viewers are made to feel valued through interacting with the channel through phone-ins, emails, tweets, requests, dedications and by voting for the “greatest pieces of classical music” for the daily Hall of Fame Hour.

In the face of Classic FM’s success and with increasing pressure from policy makers to provide “value for money” through upping listener numbers, Radio 3 decided that it had to be more “accessible and welcoming” to a wider audience, especially to people “with little knowledge of classical music.” Radio 3 began emulating Classic FM’s strategies, with listener call-ins, a lighter repertoire, excerpts rather than complete works and the repetition of popular favorites. Classic FM took notice, complaining to a Parliamentary committee that Radio 3’s duplication of its format eroded listener choice. And long-standing Radio 3 listeners, particularly the independent advocacy group Friends of Radio 3 responded with fury. They raged against the ‘dumbing down’ that catered for newbies while those knowledgeable about classical music were ignored. They lamented the loss of the old Radio 3 that many said had admirably fulfilled its public-service remit by providing them with a free education in classical music and improving the overall quality of their lives. Most importantly, they insisted that audience numbers should not drive programming strategies and called for a return to Reithian values. They rejected the neoliberal market logics that measure value only in economic terms – Radio 3 should be judged by its enrichment of its listeners’ lives, not on spend per audience member or the sheer number of listeners.

The debate about Radio 3 raises issues relevant to public service broadcasting more generally. Should tiny audiences be appealed to if there is no immediate gain in either economic or PR terms? Can public service broadcasting afford to be elitist in the austerity age? The debate also raises issues relevant to the place of the arts in the neoliberal market. Should public monies continue to fund the opera or the theatre when only a small percentage of the population patronises them? Can only those art forms that make money survive? Has Theodor Adorno been proven right in saying, “Through the total absorption of both musical production and consumption by the capitalist process, the alienation of man has become complete.”