The Warner Archive Program and Hollywood History

A month ago Sony announced that it was laying off 450 employees, most of them in the home video division, due in part to recent declines in DVD sales. The Wall Street Journal notes that last year was the first since 2002 that the film industry made more money at the box office than through home video.

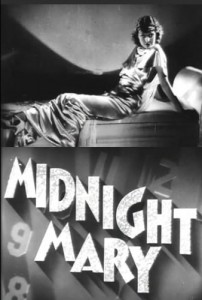

In the last decade, the profitability of the DVD sell-through model turned studio vaults into goldmines. This was a boon for students of American cinema, as even obscure films like Midnight Mary (1933) and Second Honeymoon (1937) received expensive digital restorations and were accompanied on DVD by bonus features like documentaries, historian commentaries, and contemporaneous cartoons and newsreels. The classics divisions of Warner Bros., Fox, and Sony in particular have helped to expand the classical Hollywood canon and educate audiences about Hollywood history.

In the last decade, the profitability of the DVD sell-through model turned studio vaults into goldmines. This was a boon for students of American cinema, as even obscure films like Midnight Mary (1933) and Second Honeymoon (1937) received expensive digital restorations and were accompanied on DVD by bonus features like documentaries, historian commentaries, and contemporaneous cartoons and newsreels. The classics divisions of Warner Bros., Fox, and Sony in particular have helped to expand the classical Hollywood canon and educate audiences about Hollywood history.

Today, consumers’ shelves are full and major retailers have either gone under (Tower, Sam Goody) or stopped stocking classic titles (Best Buy). In an effort to squeeze the few remaining dollars out of the home video market, studios have begun selling DVD-R copies of library titles that are burned on-demand. Warners has led the way with its Archive program, and Universal and MGM have followed, if somewhat tentatively, via Amazon.

These programs have been beneficial in one important respect – sheer quantity. In an example of “long tail” retailing, Warners has made available nearly 500 films in the last year alone. Historians and fans alike now have access to films that would have never received a retail store release, like the “Dogville” shorts. It’s possible that the bulk of the WB, MGM, and RKO libraries will be available in just a few years, making these programs unprecedented research tools for film historians.

However, this distribution system also reinforces the diminished visibility and accessibility of classic Hollywood in the marketplace. Previously, Warners released its classic films to retailers in boxed sets where films cost $5-$10 each. Warner Archive discs, in contrast, are sold a la carte for $20 each. They are not available via brick-and-mortar stores, or from Netflix, which refuses to stock DVD-Rs. Under this new system, consumers are much less likely to take a risk and “blind buy”, meaning there is much less chance that hidden gems will find an audience.

By limiting access to these discs, Warners cannily positions them as “rare”, which increases their value as commodities and allows the studio to sell them at a premium. Warners targets DVD collectors with their “Insider” program, even as they strip away the aspects of DVDs that appeal to that audience. Archive discs, typically sourced from old video masters used for television broadcast, are often inferior in audio/video quality – this is especially noticeable on today’s huge HD sets. They also lack any special features that might analyze the films or provide historical context.

The manufactured-on-demand (MOD) model represents a way for studios to retain some of the value of their libraries in the midst of DVD’s inevitable decline. It allows them to cut production costs (no expensive restorations, no special features, no unsold product taking up warehouse space) while also raising prices. The “less for more” policy risks alienating collectors, but Warners claims the program has been extremely successful. Unfortunately, with few classic movies justifying the expense of a Blu-ray release, it appears likely that the less familiar (and potentially more interesting) nooks and crannies of Hollywood history will remain hidden to most. Then again, there’s always Turner Classic Movies…

Good article and it sounds like they are taking a cue from the major labels who re-release “classics” with, in many cases, dubious bonus tracks and extras such as studio outtakes for a premium. This specific re-release strategy of old masters has a long yet undocumented history, something that media scholars would do well to study. It’s also a place where we could learn from economists regarding price theory, which I know very little about myself. Look forward to this discussion!

Great look at the changing economics of home video. We’re at the end of the boom, that’s for sure, and I wonder how long certain distributors (notably Shout! Factory, at least for my tastes) are going to be able to survive on only a slew of niche products. I’m increasingly of the opinion that we’d better start snapping up all those DVDs and box sets that’ve been available since the early 2000s, if not longer; they’re going to start disappearing from availability sooner than we’d like.

Lost amongst most of the hype of the long tail and “niche-ization” of popular culture is exactly the issue you pinpointed: when does even a niche product cost too much? Every reissue still costs money, in many ways (legal, regarding the labyrinth of rights, in particular). Sadly, the alternative to MOD is SOL (or, if one is not squeamish, trolling the internet): i.e., if they can’t figure out a way to make money off of it, it’s not going to happen. This is why those recently discovered Jack Benny radio shows are almost certainly never going to be released. We can’t take DVD releases for granted any more.

Moreover, if I were to gamble, I’d bet that a decade from now recordings commercially released on a physical medium (e.g., a five-inch digitally encoded plastic disc) are going to be marginal to the industry. However, the cost question–the necessity to make money on whatever is made available–will still dictate what we can download.

Oops; sorry for all the italics!

[…] to see just how precarious our film catalogs actually are. In a post for Antenna, Bradley Schauer points to two notable stories about DVD consumption. First, Sony announced that it is laying off 450 […]

Whether it’s books, CD’s, DVD’s or anything else, print on demand is going to be the way of the future for those customers who want a physical product. As lovely as the instant gratification of immediately being able to download and view products, I still sell many more physical books than I do downloads.