Nationalism, nul points, or, How Eurovision Makes for a Better World

With the start of the World Cup in two weeks, audiences around the world will put on their replica shirts, paint their faces, and mount little plastic flags (usually produced in China) to their cars. With the skeleton of nationalism they will also get its inevitable associates jingoism and chauvinism out of the closet. France, as unorthodoxly as practically, decided to combine both events by sending its official World Cup song to the Eurovision finals. However, in contrast to the World Cup, the Eurovision has the unparalleled capacity to make that skeleton of nationalism a little less scary – by putting it into a camp costume and acoustically accompanying it with a mix of popular music that happily draws on the grotesque as much as the popular, on the amateurish as much as the professional, on kitsch as much as local taste cultures.

With the start of the World Cup in two weeks, audiences around the world will put on their replica shirts, paint their faces, and mount little plastic flags (usually produced in China) to their cars. With the skeleton of nationalism they will also get its inevitable associates jingoism and chauvinism out of the closet. France, as unorthodoxly as practically, decided to combine both events by sending its official World Cup song to the Eurovision finals. However, in contrast to the World Cup, the Eurovision has the unparalleled capacity to make that skeleton of nationalism a little less scary – by putting it into a camp costume and acoustically accompanying it with a mix of popular music that happily draws on the grotesque as much as the popular, on the amateurish as much as the professional, on kitsch as much as local taste cultures.

For all overt nationalism on show during the contest and on the hundreds of message boards and millions of Twitter feeds that reflect Eurovision’s smooth transition from the broadcast to the convergence era, last Saturday’s Eurovision in Oslo [those who missed the contest can watch the complete broadcast here] once again underlined the Eurovision as a truly transnational media event that sometimes purposefully, but more often unwittingly undermines nationalism by championing its two natural enemies: silliness and inclusiveness.

As the great Charlie Chaplin realised more than 70 years ago, nationalism – like fascism – relies on being taken seriously: sport in its overt display of masculine chauvinism is not coincidently nationalism’s favourite vehicle. The small shoulders of the often young and hardly known performers at the Eurovision carry this heavy ideological burden less well. Can a Moldovan sense of nationhood really rest on a Eurodance-y Roxette rival band (watch out for the cameo by a young Bill Clinton)? Will the linguistically torn Belgium really rally around Tom Dice – who as a fellow viewer rightly (but rather unhelpfully only after I had placed a £2 bet on a top three finish) pointed out to me is more James Blunt than David Gray, as I had mistakenly assumed? Who would really believe that Spain hoped that a performance so surreal that the appearance of pitch invader Jimmy Jump could have easily gone unnoticed would garner acclaim and triumph? And did hapless Josh Dubovie who built on a recent run of last place finishes by the UK really add to a sense of British pride?

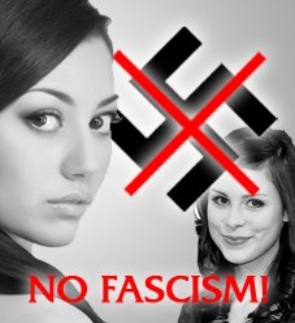

This is not to say that the Eurovision, as many other areas of popular culture, is not utilised in the articulation of a plethora or political and historical discourses. In recent years, the arrival and success of former Warsaw Pact states (and successor states) has lead to hostile reactions of Western European audiences suggesting such countries should hold their own “Soviet Song Contest.” This year, the victory of 19 year old Lena Meyer-Landrut (only Germany’s second victory, and first since 1982) over bookmaker’s favourite Safura from Azerbaijan lead to equally angry reactions from Eastern European viewers alleging that Germany’s economic power had swayed juries and voters and noting that voting for Safura was one’s antifascist duty as illustrated in such fan craftwork:

The point is not that the Eurovision doesn’t allow for such discourses – only, as everything else surrounding the contest, they are very hard to take seriously (see, for instance, the detailed discussions on the YouTube pages linked above, with one viewer claiming that “my parents sent a SMS for Azerbaijan to win yesterday, so only my family sent 3 SMS-s for Azerbaijan but we all saw that Safura didn’t gained [sic] a single points from Albania when the results were announced. It’s FAKE”). What matters is not whether Azerbaijan did or didn’t win; whether the Cypriot entry is from Cyprus or Swansea (it’s the latter); nor whether many in the German diasporic community share my profound sense of embarrassment over the heightened exposure of Meyer-Landrut’s at best spasmodic command of English grammar, syntax, and pronunciation following her victory. What matters is that the European Broadcast Union’s inclusive membership policy allows for a contest in which Azerbaijan as much as Germany, Israel as much as Iceland, Turkey as much as the United Kingdom share a common European stage, creating a European landscape that in David Morley’s word’s is “more than a nation-state writ large”: a Europe that is many ways the opposite of the nation state: inclusive and hard to take seriously! To me, that’s as much as I could ever hope for of Saturday night television.

I’m trying to think of examples of camp nationalism, but am instead finding yet more examples to suggest how often transnationalism, multiculturalism, and pluralism are camp (food fairs, themed restaurants, amusement park rides). So maybe the antidote to hardline nationalism is … silliness? 🙂