From Painting to Cinema: A Skeptical Look

What can the history of painting tell us about the history of cinema?

What can the history of painting tell us about the history of cinema?

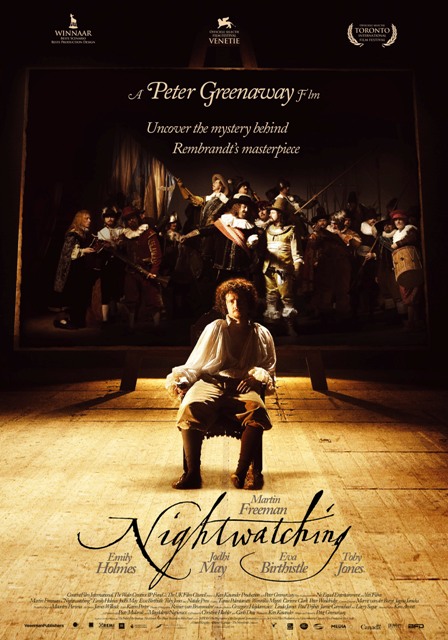

Faced with a piece like this recent one from The Guardian, one can’t help but ask whether claims about filmmakers “working from” the styles of painters have any explanatory value. What kind of causal weight does one grant to a remark like Martin Scorsese’s that in the visual style of his debut feature Mean Streets (1973) he had Caravaggio in mind? Or consider the effort among some critics (here and here) to determine whether Pedro Costa’s visual style in In Vanda’s Room (2000) or Colossal Youth (2006) owes more to Rembrandt or Vermeer. A skeptic will insist that a distinction or two needs to be made.

For critics looking to provide the curious viewer with a helpful frame of reference to initially encounter a work, or to create associations between various artists (and even arts) in order to legitimize a filmmaker in the marketplace, language comparing painting and cinema might be useful. The expression “strategic discourse” comes to mind.

But the move “from painting to cinema” becomes an issue when the aim is to isolate and clarify the causes of a filmmaker’s art—that is, when one wishes to explain a film or a group of films. Claims like, “Costa developed this look by working from principles and techniques borrowed from Rembrandt,” should raise doubts.

On the surface of it, there doesn’t appear to be a problem. Yet, if we accept that the aesthetic history of cinema amounts to a series of artistic solutions to specific problems that arise (as art historians E.H. Gombrich, George Kubler and Michael Baxandall might), then to what extent can a filmmaker’s art “be like” or “draw on” a painter’s? Both a painter and a filmmaker work with two-dimensional surfaces, and therefore share problems associated with creating the impression of three dimensions on a flat plane. Even 3-D films have to address these problems. Filmmakers, for their part, have the added problem that their pictures move (however one wishes to construe this process). How to create a sense of time and space in individual takes linked through editing leads to a whole array of tensions and difficulties that painters never address directly. In the case of a Pedro Costa, this means editing together separately composed takes, and considering the relations between them. And what of sound-image relations? Certainly, one might strain to link something a painter does or something a viewer of painting perceives (like sounds evoked through visual representation) to what a film viewer perceives, but this would fall short of accounting for the problem-solutions arrived at by a filmmaker.

What value, then, is there in positing that filmmakers inherit the same problems as painters? At best, they might share, first, a set of quite general interests or principles and, second, lighting solutions. However, in order to explain a movie, we need more than this. After all, with lighting solutions “borrowed” from painters, filmmakers still have to deal with the limitations and “quirks” of their own tools, which are not the same as those of painters. Even where filmmakers borrow such solutions there is a translation process that intervenes. They don’t use the same solutions as much as they approximate them. So, painters and filmmakers, in cases like this, deal with similar, but ultimately distinct, problem situations. To argue differently is to lose details critical to one’s explanations.

Still, the question is tantalizing: can painters be sources for ideas about editing and staging in successive shots? Appeals to painters may not give historians of film style a set of proximate causes qua problem-solutions, but they may well furnish some slightly more distant explanatory matter.

Really interesting piece, Colin. I’ve been thinking about the way that painting is employed in a “strategic discourse” for television lately, albeit in a slightly different way – not necessarily comparing particular texts or showrunners’ styles to painters, but instead the TV itself as a “fine painting on the wall.”

My husband and I recently purchased a sizeable flat panel TV, and shopped various different wall mount to go with it. Everywhere, it seemed, from product descriptions online to store sales associates and customer reviews, we were inundated with the “flat panel TV as wall art” discourse that constantly likened a wall-mount TV to a fine painting installed in your home, functioning in various contexts – like describing the “amazing artistic quality” of HD and various technologies like plasma, LCD, LED, etc. The “painting on the wall” discourse was also used in the instruction manuals for our wall mount to encourage and describe the ways one can hide the various cables, cords, etc. (by running them through the wall).

So, here, we see this strategic discourse used to legitimate/value TV’s place in the home (and accordingly TV as a medium) and also an interesting tension between *highlighting* the technological intermediaries of aesthetic value (HD, plasma, LED, LCD, etc.) and the importance of *hiding* any visible or material reminders of its technological connectivity (by putting all the cords and plugs in the wall to achieve the affect of a painting on the wall).

Lindsay,

Thanks for this. I hadn’t thought of the problem in this way, but this is really a fascinating aspect of the marketplace for televisual products (in this case, not the shows, but the actual “box,” if that’s not a totally outdated term).

Although my question, for the most part, is a different one– related to the causal history of cinema– the “strategic discourse” aspect is no less significant, as you show. I wonder, for instance, whether such “top-down” encouragement (what some call “culture”) influences more than just purchasing habits. I wonder if the encouragement to view the latest TV as “quality art” in itself is related in any way to certain viewing habits. Are those who are susceptible to this kind of appeal to buy a TV as a “painting on a wall” (and I don’t mean to mock them) correlates with watching certain “quality” or “arty” shows or consuming “quality” or “arty” blu-rays, and watching them in certain ways.

For me, the big question that follows from this is whether those on the other end (“producers” in the broadest sense, of TV, of movies, of blu-rays) factor these kinds of things into their creative process. I have doubts for now, but it’s a question worth pursuing.

Thanks for the stimulating response!

Sorry, there was a little typo in my reply. In the second paragraph, I *meant* to ask: “Does being susceptible to this kind of appeal to buy a TV as a “painting on a wall” (and I don’t mean to mock them) correlate with watching certain “quality” or “arty” shows or consuming “quality” or “arty” blu-rays, and with watching them in certain ways?”

Nice post, Colin. I particularly like your allusion to ‘strategic discourse’ in relation to this trend.

I expect that painting can influence filmmaking and provide ideas for the ‘look’ of films. It would be interesting to hear Scorcese’s thoughts on the matter to see whether or not he was influenced in this manner. On the other hand, it seems to me that the trend you observe might be in large part a function of the framing and legitimation concerns to which you allude in paragraph three. This trend might be in large part attributable to the ongoing desire to distinguish film from other forms of popular culture and, within that field, ‘legitimately’ artistic films from movies. Associating a film’s look with the style of a famous painter is a quick and easy way for a cultural intermediary such as a popular press critic to establish that a film is a serious piece of art that is both worthy of sustained attention and best appreciated by those who understand the refined and often elusive qualities upon which the comparison has ostensibly been made. These poetic and impressionistic characterizations are matters of taste that speak to those who are already invested in them (and thus do not need to be able to withstand intense critical scrutiny). They provide a useful counterpoint to characterizations of comedies as inspired by the sketch/set piece format that predominates in some television forms or action films as influenced by the style of music videos.

It seems an obvious point, but I also note something of a desire to elevate the artist here. Where the visual style may be attributable to a collaboration between different members of the creative team, it seems as though these arguments are often made in order to substantiate director-as-auteur claims.

Chris, allow me comment on your last point– although, certainly, there is a great deal to be said about the other matters you raise.

“Attribution” is a complex issue. Who’s responsible? Do we grant all credit to the one billed as “the auteur,” or is it more accurate to attribute a body of work to the shared agency of the “auteur” and his collaborators?

If you’re interested in this question in the context of painting, see Svetlana Alpers’ wonderful study, Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (1990): http://books.google.ca/books?id=DKmAJdq5LEYC&dq=rembrandt's+studio+alpers&printsec=frontcover&source=bn&hl=en&ei=Qwx4TJWhK5H9ngfprLzBAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false.

In her book, Alpers shows how “Rembrandt” became a market commodity, much like “Martin Scorsese” is, positioned in the marketplace as the sole agent behind the paintings; but, in fact, Rembrandt’s inventive process was highly collaborative. So, I agree: discussions about the relations between the individual styles of a Scorsese and a Caravaggio benefit the former by painting him (pun intended) as the sole creative force behind a work.

Despite this trend, there is a lot to be recommended in a collaborative approach to artistry in various media. I like this quotation from Paul Valery, from “Difficulté de définir la simulation,” in a 1927 issue of the Nouvelle revue française:

“It takes two to invent anything. The one makes up the combinations; the other chooses, recognises what he wishes and what is important to him in the mass of things which the former has imparted to him. What we call genius is much less the work of the first one than the readiness of the second one to grasp the value of what has been laid before him and to choose it.”

In my estimation, this kind of thinking applies to the most modest and self-effacing journeyman, like the filmmaker Robert Wise (of The Haunting [1963] and Star Trek: The Motion Picture [1979] fame), or to the most revered “individualist” who claims, or is construed as having, responsibility for every aspect of the work, like David Lynch.

Still, a fair-minded account of the work of many filmmakers cannot simply attribute the work to “collaboration.” While it is true that a cinematographer or set designer or editor has agency in the making of Scorsese’s films, in most cases he will be the one responsible for posing the problems that the work is meant to solve.

Thus, it’s probably best to chart a course between absolute individual control by the auteur and sheer distributed agency among the group of collaborators. A filmmaker with a set of aesthetic commitments or interests will, for the most part, set the problems– without which his collaborators would have no task on which to focus their skills.

That’s the way I conceive things. Does this jibe with your complaint about too much agency being allotted to “the auteur”? Thoughts?

I agree with most of your points, Colin. I am aware that the production of visual art – painting, sculpture etc. – often involves the use of assistants and surrogates. In this sense, even if these activities are not conceived of as collaborative, there is invariably some form of collaboration that goes into the production process. Beyond this, there are varying degrees of what Howard Becker calls ‘cooperation’ involved in any project. As you note, it is the one with the vision – the one can set out the problems to be resolved or criteria to be met – who might deserve the status of auteur in relation to his group of collaborators and the cooperators down below.

At the same time, this sort of nuanced reading doesn’t seem to arise so frequently in popular discourse. One is more likely to find the elevation of the romantic genius figure. This leads me to once again wonder why we are invested in the idea that great art is often produced by a single individual as the result of some form of divine inspiration. It seems to me that the characterizations of Scorcese that you initially addressed were endeavoring to perform this move by likening the auteur director to the painter. While we acknowledge that each of these activities are collaborative and cooperative in various ways, this sort of characterization serves to reinforce the conventional image of the artist.

I guess that this all makes me wonder why we continue to be so invested in this particular idea and how it relates to the questions of taste I alluded to above. I think that this likely has something to do with the desire to understand art film as an authentic art form – a mass medium with certain anti-mass sensibilities, to use Keir Keightley’s phrase. He has made similar observations about the invocation of romantic tropes of authenticity in rock culture.

Colin,

I’m wondering if we shouldn’t back up a step. You say that filmmakers at best might share “general interests or principles” with painters but move past this as if to suggest that it is superficial. But, I think that this is precisely what filmmakers mean when they claim to be influenced by painters. More than specific problems or solutions, they are drawn to the iconography. For instance, John Ford kept books of Remington and Schreyvogel’s western paintings next to his bed for years, which he claimed to scan every night before he went to sleep for ideas. But I don’t take him to mean that he was looking for specific staging, lighting, or editing techniques. Rather, he was simply interested in the way the cavalry were represented, the way they wore their uniforms, how the Native Americans would assemble at the top of a hill and watch the officers as they passed in a line underneath them. Similarly, how many neo noir directors would claim to be influenced by Hopper? I don’t take them to mean that they inherited the same medium specific problems as Hopper, but rather that they liked the way the hats look, or the idea of the solitary man at the diner at night, etc. As you suggest, their problem becomes how to translate this iconography to the screen.

You also note that filmmakers have to deal with the limitations of their own tools, such that being influenced by painting necessarily involves approximation or translation. Absolutely true, but this fact doesn’t necessarily disqualify painting as playing a causal role in the explanation of a filmmaker’s style. In fact, I imagine that if probed, many filmmakers who claim to have been influenced by painting would readily admit that they are speaking a bit figuratively, that medium specific translation was still paramount. For instance, Stan Brakhage always claimed to have been deeply influenced by Abstract Expressionism, well before he actually started painting on film. What he meant was that he was approximating action painting by developing a full-bodied approach to shooting with his Bolex. To watch him do it is quite amazing – it kind of resembles a parry and thrust, with him holding the camera close to his chest and then almost physically rocking back and forth. This is how the famous shots of the baby in the grass in ANTICIPATION OF THE NIGHT were created, for instance. So, for him, saying that he was influenced by Pollock simply meant that he considered his “embodied camera” aesthetic to have certain loose affinities with action painting.

Incidentally, two films that engage directly with the questions you raise are Godard’s PASSION and Straub/Huillet’s A VISIT TO THE LOUVRE. In the former, Godard actually recreates a number of famous paintings in tableau style, while the latter consists of static shots of framed paintings that hang in the Louvre, as if to suggest that a static camera and minimal editing is the only way to preserve the integrity of the artworks.

Finally, we should not forget that there are a group of filmmakers who do share some of the very same concerns as painters: filmmakers who actually paint their films. Of course, here I’m thinking of Brakhage, Lye, McLaren, Harry Smith, Jen Reeves, etc. But here, too, we’d have to acknowledge that translation is involved. Film stock is not the same as canvas, editing introduces new possibilities, and, of course, we’re seeing 24 paintings every second.

But perhaps as the examples of Brakhage, Godard, Straub/Huillet, and the handpainters suggest, this problem takes on an entirely different cast in the avant-garde, which has always been closely aligned with the art world.

John,

Thank you for the excellent reply. You’ve given Antenna readers, myself included, a lot of ideas and examples to think about.

If you don’t mind me saying so, I think we disagree much less than you suggest. Still, given that you raise questions about it, I should further clarify my position on causation. Recall that the basic issue I raise is about the “causal weight” we place on explicitly professed or merely inferred “painting-to-cinema” influences. When Scorsese claims Caravaggio as a direct influence, and when Brakhage cites Pollock, some unfortunately accept the implied relation as a *necessary and sufficient condition* to explain the look of films like Mean Streets and Anticipation of the Night.

I find “painting-to-cinema” claims of direct influence slightly misleading. I don’t think filmmakers should be expected to excise such claims from their rhetoric—they are playing a delicate self-presentational game—but I do think that historians and cinephiles can do more to raise awareness about the craftsmanship and artistry that intervenes between the iconography borrowed from painting and the final film made. Doing so can only promote the specific creativity of filmmakers, who aren’t, after all, painters.

Let me underscore this point with another example. We have two artifacts. Artifact A, a painting by Paul Cezanne, and artifact B, a film by Robert Bresson. Or, if you prefer, we have two artists. Artist A, the painter Cezanne, and artist B, the filmmaker Bresson. To posit a direct influence of artifact A on artifact B is, considered from a slightly different angle, to claim that artist A’s ideas or works “moved the hand” of artist B. It is to make the first an agent, in some measure, in the art of the second. Without a Cezanne, we wouldn’t have a Bresson. Or, more modestly, without this aspect of Cezanne, we wouldn’t have that aspect of Bresson.

As an admirer of Brakhage, doesn’t it make you slightly uneasy—because of your sense of the “facts” and your concern for Brakhage’s “status,” to use a crude expression—to hear that without Pollock we’d have no Brakhage? Or, that without Pollock’s idea of action painting we wouldn’t have Anticipation of the Night? One of the reasons that statements like this appear to be lacking is our sense that filmmakers have creative agency in the making of their own films.

Now, in my estimation, one of the most effective ways to account for that creative agency is by viewing filmmakers as artistic problem-solvers. For Bresson—accepting for the moment the Cezanne link some scholars and critics propose—the problem was, How can I make use of Cezanne’s compositional commitments and strategies to devise a new “non-theatrical” way to compose my shots, edit my films, and tell the stories I choose to tell? First, the benefit of putting the relation between Bresson and Cezanne as a question that would lead to a set of filmmaking problems requiring solution, as opposed to the shorthand “Cezanne influenced Bresson,” is that we restore to Bresson the creative agency he in fact had. Second, we also acknowledge that part of Bresson’s inventive process involved reimagining Cezanne through his own medium. Bresson’s medium is cinema—he inherits a tradition of problem-solutions in cutting, lighting, framing, staging and so on—and so for Cezanne to be of use to him creatively, Cezanne had to be *filtered through* these traditions of cinematic artistry that Bresson elected to repeat, revise or reject.

So, yes, the influence of painting on cinema often is a valuable causal lever—to the extent that actual influence can be established—but it’s not a proximate one. My understanding is that it is a secondary or tertiary cause.

On a side note, I hope this answers the “avant-garde” exception you cite. Bresson was in fact viewed as exemplar of the “nouveau avant-garde” of the immediate postwar era in France. Perhaps more importantly, though, I’m not sure, based on what you argue, that proximity to the art world is a distinction with a difference in this matter. The same problems seem to apply.

Don’t they?

Chris,

I think you’re spot on: why is this attitude still with us? I recently resigned myself to the notion that the “auteur” discourse will overwhelm the benefits of the collaborative perspective so long as it remains convenient, beneficial and attractive to accept the “one-work-one-artist” view.

But this doesn’t mean that I’ve given up. As a film scholar, I view the raising of awareness of the art of filmmaking as one of the cultural projects I contribute to, if that doesn’t sound too lofty. Still, opposing the standard view on this issue is difficult to do, if only because filmmakers themselves have refined a rhetoric that appeals to and sustains it.

The state of affairs is such that questions about the collaborative dynamic between a revered auteur and his editor, for example, or about how a filmmaker interested in painting still owes his artistic solutions to “the movies” are often met with three kinds of charges of vulgarity:

1) that one is vulgarly demystifying the auteur;

2) that one is vulgarly granting too much credit to the measly commercial art of cinema;

and 3) that one is a vulgar “film fan” who fetishizes “behind the scenes” featurettes and technical journals.

How does one oppose this trend?

Well, I have a few ideas, but fear that they might at times sound a little too hoity-toity. Please know that this is not my intention. First, I think we can encourage people to view the understanding of collaboration and the history of film style as central to a basic appreciation of movies. But this is a tall task. Nonetheless, if we expect that intelligent and discerning people (of any class, culture, what-have-you) should be able to use relatively fine language when talking about good food, good painting, good music, and so on, why can’t people be expected to do the same for movies and television and video games? The problem is that each of these things has its own language of appreciation, and learning a new language to be able to chat intelligently about video games requires effort.

We can also make the denial of collaboration and the history of the ways filmmakers tell stories and stage and edit shots the kind of thing that removes the denier from conversations with thinking and sensitive lovers of culture. This means, in my view, either discrediting an overreaching “auteurism” or fighting fire with fire, to coin a phrase, by using metaphors from the more established arts. If someone denies that the dynamic between the director and the set designer is significant to film appreciation– a merely technical matter when compared to the director’s “vision,” the emotional effects of the story and the actor’s interpretation of a role– then one could wield the language of a musical critic by pointing out that the relation between the auteur and his creative collaborators is as sensitive as that between a conductor with his musicians. And so on.

I’m beginning to sound perhaps a little too dismissive and lofty here, so I should add that some of the most knowledgeable filmgoers I’ve known are strict auteurists (even if they wouldn’t put it that way) and yet have some of the subtlest things to say about how and why movies look and sound the way they do.

Still, I can’t help but feel that there are benefits to educating the public (and ourselves, as critics and scholars) about the “marketplace” functions of auteurism, which seems to prompt Scorsese to claim Caravaggio as a predecessor, and the ways such claims affect, or do not, the creative decisions that actually go into making the movies we love.

John,

Allow me to quickly add a point on why I think a consideration of “problem-solving” yields primary or proximate causes.

To explain Anticipation of the Night, we can appeal to various “materials.” But ultimately, as you know, we will tend to create a hierarchy of factors. To explain some of the film’s shots, we need more than just the fact that Brakhage looked to Pollock. Evoking Pollock gets us something that perhaps looks like Brakhage’s compositions, but *getting closer* to Brakhage’s problem situation will help us explain the finer contours of the ones he actually came up with. Lighting conditions; the kinds of camera and stock used; traditions of composition and framing that would have been on his mind, whether those in the American avant-garde, or those outside it; and so on. These resources would create productive pressures and tensions the relief of which would require Brakhage to deploy his ingenuity and skill (physical, intellectual, artistic, etc.).

Thus, “Abstract Expressionism” is a factor in why a film like Brakhage’s, based as it is on the style’s techniques and principles, looks the way it does, but the art-world source is insufficient on its own to get at why Anticipation of the Night specifically has the style it does.

Colin, if I may, let me recapitulate your argument to the best of my understanding and submit a few questions. From what I take you make five core arguments in your post. 1) Filmmakers work within a specific set of technical, conceptual, receptive, economic, and historical references, which you call a ‘marketplace’. 2) While there are correlations between problems and processes in cinema and other media—for example painting—such correlations must be ‘translated’ to apply to actual practical means of making and viewing movies. In previous scholarly formulations, different media ‘marketplaces’ have been conflated and associative determinations have been made between what are actually very different processes that demand very different problem solving. 3) Hence looking at the act of ‘translation’ between ‘marketplaces’ reveals something about our _assumptions_ regarding the creative process demands clarification. 4) Aesthetic production involves reciprocation between a particular producer and an audience–but additionally a history of production and reception. Work is essentially deposited into a ‘marketplace’ strategically, where it will diffuse into available receptive currents. A filmmaker (and all who are involved in the production of a film) must consider how to position work, and calculate how it will be received and compared to other works. 5) ‘Great’ works are essentially well-calculated deposits by those who understand the artifice of production, the receptive environment, and the momentum, if you will, of how previous works will inflect upon potential reception. In other words, with film specifically, good ‘choices’ made among necessary commitments maximize receptive compensation among available ‘strategic discourses’. Well-received works may be defined as objects that have diffused into ‘marketplace’ currents as closely as possible to a producer’s intent. But not because the film is a singular work of ‘genius’; the producer will have successfully managed multiple levels of exigency in the production and distribution of his/her film.

This is basically a theory of procedure and practicality. There’s a real contribution here in that you demystify conditions of aesthetic deliberation. But there are several theoretical assumptions I wonder about. I’ll state them generally and respond to your follow-up more in depth. I don’t have the deep film knowledge that John does, so I won’t pretend to. But I wonder: 1) Do deliberative actions always serve available meanings with fidelity? In order to produce a great work, you argue, a filmmaker must grasp the value of previous models and available conditions and navigate said conditions correctly. Contributions and the possibility for evaluative shifts must come from an ‘expert’ of several categories of facilitation (mentioned above). However, are there sets of meanings that may not overlap in a ‘marketplace’? It seems that your definition of ‘translation’ attempts to speak to conditions that lack inherent overlap, but my reading still locates the assumption that regardless of a medium, aesthetic approximations will refer to agreed upon—actual—conditions. 2) If you accept my characterization, is a well-received filmmaking ‘problem solver’ merely adding to a set information by inflecting further upon it, or do they shift possibilities for evaluation with their contributions? To phrase a little differently, if an artistic work is received as high quality, is it because the artist has elucidated something already present and waiting to be articulated by managing the ‘social marketplace’ with expertise, because they have ‘translated’ between media in ways that inflect upon both aesthetic processes? Or is it possible for there to be aesthetic production and reception without inherent intent; or perhaps less strongly stated, I wonder how you would evaluate _why_ some works are received as accidental masterpieces? This isn’t a frivolous question. Even if you respond that a ‘great work’ is the result of a well-defined placement of an object among otherwise dynamic or chaotic conditions—a placement that reflects as closely to an original intent as possible—you still have to concede that the producer or film object has articulated something more clearly than other producers and objects; and such an articulation can only be made upon a set of embodied or assumed contexts.