Open or Closed? Mad Men, Celebrity Gossip, and the Public/Private Divide

This week’s Mad Men is all about gossip — and not just because that’s what I study.

This week’s Mad Men is all about gossip — and not just because that’s what I study.

As has been the case in several excellent episodes over the course of the series, a significant cultural event anchors “The Suitcase.” The title bout between Cassius Clay and Sonny Liston provides open avenues for characterization: Trudy meets Pete at the office beforehand, creating an opportunity for Peggy to witness and react to Trudy’s pregnant body. Even the fact that Peggy would miss the fight underlines her discomfort and disaffiliation with events and practices that are meant to be universal.

The fight also clears out the office, allowing the confrontation/reconciliation between Don and Peggy to take place in isolation. But most importantly, the fight itself features two celebrities — two constructed images. And what people say about these images — how they gossip — reveals as much about the speaker of the gossip as it does about the subject.

Gossip — whether about celebrities or prominent figures in our own social lives — allows us a way to work through issues. Gossip works to socially police beauty and cultural norms, but also speaks the unspeakable, permitting us to talk about things we’re otherwise not comfortable explicitly discussing. When Don admits his hate for Clay — “Liston just goes about his business, works methodically,” while “Cassius has to dance and talk” — he’s essentially declaring what he values and dismisses in a man.

The cultural environment of 1960s was characterized by the expansion of celebrity. With the star system dead and buried, fan magazines were increasingly turning to a broad range of public figures as grist for the gossip mill, including singers, politicians, and sports figures; Photoplay had declared Jackie Kennedy America’s “Biggest Star” in 1961. A celebrity was more than just someone who was good at his job. He also disclosed something about his personal life (his childhood, his romances, his favorite foods), intermingling the public and the private and offering the resultant image for consumption.

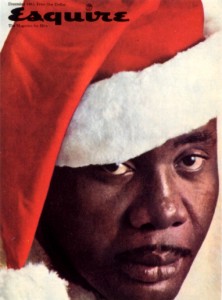

In this way, Clay vs. Liston was more than a fight between two men. Liston was an ex-con, had mob associations, was terse in interviews, and in December 1963 appeared in close up on the cover of Esquire dressed as Santa Claus, looking, according to Sports Illustrated, “like the last man on earth Americans wanted to see coming down the chimney.” Liston’s handlers forced him to pose for the Esquire cover; he seemingly preferred to keep quiet and do the job. In contrast, Clay, the self-declared “greatest,” loved the spotlight. He had a publicity team; he loved to spout bombast. Clay was the future of celebrity, always eager to provide copy, later intermingling his personal political and religious beliefs (“I don’t have no quarrel with the Vietcong”) with his “profession.” Of course, Clay won the fight. And Don lost, both figuratively and financially.

Which brings us back to Don and Peggy — representatives of two approaches to the public/private divide. Don’s attempts to shelter his past is more than a straightforward attempt to shed the remnants of Dick Whitman. He doesn’t talk about his past, especially not at work, because, in his conception, it’s simply not pertinent. Or, as Chuck Klosterman just Tweeted, “Don Draper would hate Twitter.”

Peggy’s past and personal narrative explicitly informs her work. While she shields aspects of her life — her pregnancy, her relationship with Duck — she is always forthcoming about her family, where she lives, her (lapsed) Catholicism. She recognizes that the private, whether yearnings or biographical details, are readily becoming available for exploitation and public consumption. Intimacy — or at least the projection of intimacy — is increasingly crucial for success, as so perfectly embodied by Dr. Faye, whom Peggy clearly admires. She doesn’t fully embrace this shift, but also recognizes that she can’t fight it.

Something crucial happens, however, when Don chances upon Roger’s tapes, which disclose the intensely private details of Roger and Cooper’s pasts. Peggy exclaims “Why are you laughing? it’s like reading someone’s diary.” And, of course, it is: a diary that Roger plans on publishing and from which he hopes to profit. It’s gossip, intended to construct an image of Roger Sterling for public consumption. The surprise is that Don’s eating it — and loving it.

Here’s our turning point. In the diner, Peggy returns to the gossip about Bert, this time in giggles. They each disclose details of their pasts, desires of their futures. Don ends up in the toilet bowl; Duck exposes Peggy; Peggy watches Don break down and weep. The episode culminates with an ambiguous yet intimate gesture, one that mirrors a gesture that Peggy attempted early in Season One, when she thought it her responsibility to make herself sexually available. Don rebuffed her then, but this time, he is the initiator.

Increased Peggy-Don intimacy (romance? closer platonic friendship?) would entail a thorough intermingling of Don’s personal and private lives, and add a very different valence to the ‘Don Draper’ image. Cassius Clay and Sonny Liston may have been the biggest celebrities of the specific cultural moment, but Don was a celebrity of both Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce and the advertising world, and what people thought and said about him revealed a lot about the image of 1960s “the ad man,” anxieties over the future of the agency, and the trajectory of the industry.

Perhaps more importantly, “Don Draper” is a celebrity of our own time. What each of us think about him and this potential relationship whispers volumes: about ourselves, our own desires, our own acceptance or antipathy towards celebrity culture, and even our conception of how a “quality” narrative should proceed.

So what do you think? “Open or closed?”

Nice summary and analysis, Annie. I was also intrigued by the episode’s focus on the Liston/Ali fight, a structuring absence. Though I read Don’s criticism, “Cassius has to dance and talk,” differently. I took it as another reference to the tense racial climate of the 1960s. Ali rubbed (white) people the wrong way because he was so flamboyant and proud. He was, in other words, “uppity.” Don likes Liston because he does his job and keeps his mouth shut.

Don has, on several occasions, revealed that he is more progressive than his peers (as when he comdemns Roger’s blackface performance and in his intial reaction to Sal’s homosexuality). But comments like these highlight the racial politics of the time, reminding us that even more progressive individuals still harbored these beliefs. Given that Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce is an entirely white work place, the show needs these moments to remind the audience about the world outside the office doors.

Absolutely, Amanda. I was reminded of this when one of my friends jokingly commented on my Facebook announcement of this post — which featured the above photo of Liston — and said “Who’s that? I’ve never seen him on Mad Men.” In other words, Sonny Liston (like blackness in general, with a few pointed exception) is not depicted, even when it plays prominantly in the narrative. Thus the “structured absence” of both the fight itself (which Don, Peggy, and the audience “watch” on radio) and the discussion of race.

And I agree that Don’s talking about not only what he likes/dislikes in a man, but also a worker, a black man, and even a woman. Flair and “uppitiness” — and selling one’s image — is not for him, as evidenced by his initial hesitance to reveal anything of himself or his work in the newspaper profile that opens the season.