Glee: The Countertenor and The Crooner

This is the first in a series of articles on these male voices in Glee.

Part 1: The Trouble with Male Pop Singing

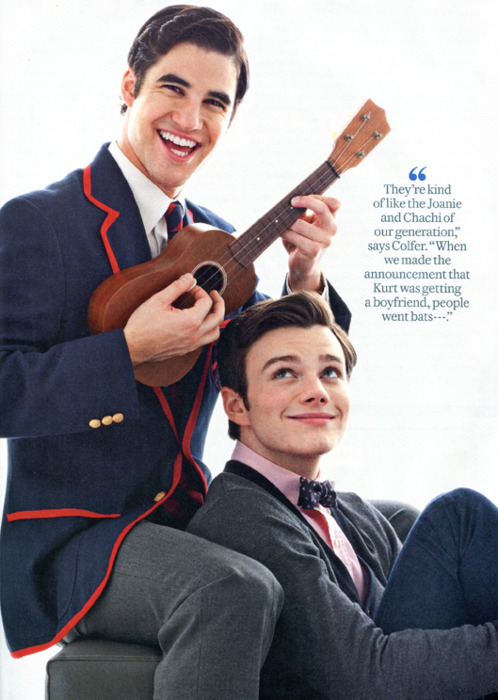

What immediately struck me about this still of Glee’s Chris Colfer (as Kurt Hummel) and Darren Criss (as Blaine Anderson) from Entertainment Weekly’s January 28, 2011 cover story is that this image might easily have been taken in the mid-to-late 1920s, but it would have been unlikely to appear in the mainstream press since that time. Attractive young men in collegiate attire, sporting ukuleles or megaphones, singing to each other and to their adoring publics in high-pitched voices was a mainstay of 1920s American popular culture, then vanished during the Depression. Even the easy homoeroticism of a boy positioned between another boy’s legs dates back to popular images of the 1920s. In the early 1930s, a combination of greater media nationalization and censorship, increasing homophobia, and panic regarding the emasculating effects of male unemployment formed the context for the first national public attack on male popular singers as effeminate and as cultural degenerates. As a result, new, restrictive gender conventions became entrenched regarding male vocalizing, and the feminine stigma has remained. Until now, that is. The popularity of Glee, and, in particular, these two singers, has made me think that American culture may finally be starting to break with the gender norms of male singing performance that have persisted for the last 80 years. Since much of my research has focused on the establishment of these gendered conventions, I would like to offer some historical context and share some of the reasons why I find Glee’s representation of male popular singing so potentially groundbreaking.

Male singing has not always been so inextricably tangled up with assumptions about the gender/sexuality of the performer. Before the reactionary gender policing of popular singing, men who sang in falsetto or “double” voice were greatly prized. Song styles such as blues, torch, and crooning were sung by both sexes and all races; lyrics were generally not changed to conform to the sex of the singer or to reinforce heterosexual norms, so that men often sang to men and women to women. Crooners became huge stars for their emotional intensity, intimate microphone delivery, and devotion to romantic love. While they sang primarily to women, they had legions of male fans as well, and both sexes wept listening to their songs.

When a range of cultural authorities condemned crooners, the media industries developed new standards of male vocal performance to quell the controversy. Any gender ambiguity in vocalizing was erased; the popular male countertenor/falsetto voice virtually disappeared, song styles were gender-coded (crooning coded male), female altos were hired to replace the many popular tenors, and all song lyrics were appropriately gendered in performance, so that men sang to and about women, and vice-versa. Bing Crosby epitomized the new standard for males: lower-pitched singing, a lack of emotional vulnerability, and a patriarchal star image. Since then, although young male singers have always remained popular and profitable, their cultural clout has been consistently undermined by masculinist evaluative standards in which the singers themselves have been regularly ridiculed as immature and inauthentic, and their fans dismissed as moronic young females.

From its beginnings, however, Glee has actively worked to challenge this conception. The show’s recognition and critique of dominant cultural constructions of performance and identity has always been one of the its great strengths. Glee has continually acknowledged the emasculating stigma of male singing (the jocks regularly assert that “singing is gay”) while providing a compelling counter-narrative that promotes pop singing as liberating and empowering for both men and society at large. Glee‘s audience has in many ways been understood to be reflective of the socially marginalized types represented on the show, and one of the recurring narrative struggles is determining who gets to speak or, rather, sing. Singing on Glee is thus frequently linked to acts of self-determination in the face of social oppression, a connection that has been most explicitly and forcefully made through gay teen Kurt’s storyline this past season, which has challenged societal homophobia both narratively and musically. In the narrative, Kurt transfers to Dalton Academy to escape bullying and joins the Warblers, an all-male a cappella group fronted by gay crooner Blaine. Musically, Glee also takes a big leap, shifting from exposing the homophobic, misogynist stigma surrounding male singing to actively shattering it and singing on its grave.

From the very first moment Kurt is introduced to Blaine and the Warblers, as they perform a cover of Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream” to a group of equally enthusiastic young men, we know we’re not in Kansas anymore. The song choice is appropriate in that it posits future-boyfriend Blaine as both a romantic and erotic dream object for Kurt, and it presents Dalton as a fantasy space in which the feminine associations of male singing are both desired and regularly celebrated. “Teenage Dream” was the first Glee single to debut at #1 on iTunes, immediately making Criss a star and indicating that a good portion of the American public was eager to embrace the change in vocal politics.

And “Teenage Dream” was only the beginning. This fantasy moment has become a recurring, naturalized fixture of the series. Just as Kurt turned his fantasy of boyfriend Blaine into a reality, so did Glee effectively realize its own redesign of male singing through a multitude of scenes that I never thought I would see on American network television: young men un-ironically singing pop songs to other young men, both gay and straight; teen boys falling in love with other boys as they sing to them; males singing popular songs without changing the lyrics from “him” to “her” to accommodate gender norms; and the restoration and celebration of the countertenor (male alto) sound and singer in American popular culture (I will address Chris Colfer’s celebrated countertenor voice in the next installment of this series). And instead of becoming subjects of cultural ridicule, Colfer’s rapturous countertenor and Criss’s velvety crooner have become Glee’s most popular couple, its stars largely celebrated as role models of a new order of male performer. It’s about time.

What a fantastic post, Allison! Truthfully, the Kurt/Blaine storyline is the only reason I’m still sticking with Glee, as I find it both compelling, refreshing and inspiring for the reasons you describe here.

No great insights from me at the moment, but a big thank you for a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece–can’t wait to read future installments!

Thanks for such an interesting perspective on GLEE and its music. I am a conflicted Gleek in that I get very frustrated with the program and its often muddled politics. But I think you’ve identified how GLEE can do some really wonderful, even ground-breaking, things with the conventions of the musical. I find myself enjoying Blaine’s numbers the most and that is mostly due to what you’ve identified here: his performances embody the pure joy of a character who knows who he is and is confident about proclaiming that to his audience. There’s no irony here and no camp.

Looking forward to the rest of your articles on this!

I am confused as to how you are operationalizing gender in this piece. While you assert that the current set of standards associated with sexuality and singing did not exist I do not agree that no such associations existed. The rules policing sexuality and singing might have been different but to posit that they did not exist for me is a bit much.

Also, I don’t know specifically which characteristics or stereotypes you feel have been associated with gender and have been reinforced by media industry singing norms. I find this section a little thin. I need to understand which types the current singers are breaking.

I also think that there is a very interesting trend of the evolution of the male pop singer within the last couple of decades. From the de-sexualized (with no sexual inclinations which is a sexual statement in and of itself) Backstreet Boys and ‘NSYNC to Disney’s desire to profit from this form in High School Musical to Glee finally allowing the sexuality of the performers to be expressed no matter what the desires of the singer.

While I am in favor of your general argument I would like to see the argument made a little bit sharper with more accurate time markers and not just “When a range of cultural authorities condemned crooners, the media industries developed new standards of male vocal performance to quell the controversy.” and more importantly a more detailed discussion of the specific gender characteristics/stereotypes and roles you are discussing.