F.ix E.verything M.y A.ss

While my larger reflections center this past Sunday’s episode, I haven’t been able to quite shake the narrative of the last. Specifically, LaDonna’s (Khandi Alexander) brutal attack and rape has kept me online pondering taser purchase and thinking about all the ways to protect my children. I’ve been torn by the representation of a Black woman being savagely attacked against the reality of Black women’s victimization receiving scant attention. Something about the senselessness and pedestrianness of it, sandwiched between the angst of an out-of-work musician and another one hustling to get work, left me with a feeling of dread and uneasiness. Living in uptown New Orleans, the frequent violence reporting exists as just that—reports about a place that does not reflect my daily reality. Notwithstanding the occasional requisite “black man on the loose” posters plastered around campus, a comfortable day-to-day occupied my psyche until this disturbing episode.

While my larger reflections center this past Sunday’s episode, I haven’t been able to quite shake the narrative of the last. Specifically, LaDonna’s (Khandi Alexander) brutal attack and rape has kept me online pondering taser purchase and thinking about all the ways to protect my children. I’ve been torn by the representation of a Black woman being savagely attacked against the reality of Black women’s victimization receiving scant attention. Something about the senselessness and pedestrianness of it, sandwiched between the angst of an out-of-work musician and another one hustling to get work, left me with a feeling of dread and uneasiness. Living in uptown New Orleans, the frequent violence reporting exists as just that—reports about a place that does not reflect my daily reality. Notwithstanding the occasional requisite “black man on the loose” posters plastered around campus, a comfortable day-to-day occupied my psyche until this disturbing episode.

The creators of Treme sat on a panel at Tulane University in November of last year where they talked about the series, its outlook, its goals, and its differences from The Wire. The focus for Treme was the culture-cality of the city and where the creators aimed their arrow for most of season one. But in this season two, amongst the sadness and pathos, they begin to address the deeply embedded divisions, corruption, and largely racialized visioning of a city wedded to a plantation economy that shapes its educational institutions, housing patterns, job allocation, and routine interactions.

In the rhythm of recent episodes, (and really mainstream jazz), the crosscutting between scenes of Sunday’s episode requires not only an intimacy with the characters but also a colossal feigned empathy with and identification of the similarities between their situations. While New Orleanians seem to love the series and are elated that it has been renewed for a third season, at least the ones that post to the Times Picayune site nola.com, talking to several Black New Orleanians strikes a slightly different note. One ex-pat felt that the story engages the city like a tourist would—centering all of the things that tourist boards foreground in their presentations of cities—food, music, local color, and if possible, exoticism. New Orleans indeed has all of those things and Treme shows them. But the pedestrian, everyday, go-to-work daily New Orleans, the feel of extended family in a place where so many have never known, will never know, any other way of life has been largely absent.

The twin emotions of comfort and resignation feel like they are just beginning to emerge in this series. While a story like Davis’s, for example, is annoying at best, distracting and offensive at worst, Albert Lambreaux Sr. and his frustration/anger with homeowners insurance, Batiste’s reintroduction to the school system and its problems (alongside the lingering dread of Katrina dwelling inside Black children), and the brutality that comes with sustained poverty through LaDonna’s rape, the killing of Benny’s son, and repeated discussions of police brutality get at another New Orleans. It is this New Orleans, the largely Black and poor New Orleans, that is only starting to gain traction in Treme.

This New Orleans is not on the tourist path; it’s beyond Bourbon and besides Mardi Gras. It is this New Orleans that privileges familial traditions and histories. It is one where talks about Indians move beyond costumes and masking. It could be the 7th Ward New Orleans and the histories of racial mixing, ambiguity, and Creolization as a way of life and division live. This New Orleans must contend with the outcomes of corruption, cronyism, greed, and nepotism.

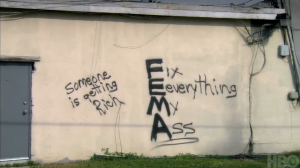

Living here in New Orleans, one of the most striking conundrums about this series is that while its heartbeat lies with the culture of Black inhabitants, it seems their larger lives cannot be the focus –perhaps due to its audience of largely white and affluent viewers. Regular, non- artistic Black New Orleanians do appear as extras and even capture central roles, as in the case of the awesome, Phyllis Montana-LaBlanc as Desiree. However, a large majority of Black New Orleanians cannot even afford to pay for the network in which this series about their city, their culture, and their lives appear. Like F.E.M.A., Treme has a certain impotence built into its existence. It’s a TV program. But as the series continues, I look forward to viewing the reconciliation or at least further examination of its polls and can only hope that its presentation provides more effect and impact than the Feds (and local government) did at that moment.

I concur with your critique about missing the larger lives of Black New Orleanians. It perhaps also should be directed at the near absence of the Black middle class in the series– the generations who live Uptown and Gentilly. This is a group that can afford HBO and still is relatively invisible to the ‘struggling’ African American musicians and entertainment industry folks.

An excellent critique of the series, especially the very disturbing rape of LaDonna. While it is understood that the series has to be tailored to attract a larger audience not living in New Orleans, the producers must also not assume that this larger audience is not interested in understanding New Orleans beyond the music and the food. People everywhere, including New Orleanians, live regular lives beyond entertainment and its attendant complexities. With that said, I remain hopeful that by the end of series, the producers would have tried (or at least attempted) to capture some aspects of everyday living for the average New Orleans resident.

I agree that the show hasn’t shown much going on in Gentilly, but we saw the condition of Albert’s house there. Similarly, I’d love to see more of Ladonna’s husband’s family, which we learned is, in her words, a snobby 7th ward creole world that looks down on her and her family “from around the way.” But their home in New Orleans East is a tear-down, so the show doesn’t focus on that neighborhood except by its absence. Yet in those two characters and their families it does look to me like there are variations of racial and class identities that could be more developed.

Too bad you feel that way about Davis! I think his character is extremely important to understanding race and class in the city.

I just had to amen the assessment of the Davis McAlary storyline as “annoying at best, distracting and offensive at worst” (and I certainly weigh in on the “at worst” end). While I agree with Julia about the importance of understanding race and class in the city, I see Davis’ character as undermining this understanding, not promoting it. I can think of countless examples when Davis’ character usurps black characters’ agency or expertise (or rage, in the case of episode 6 when he is trying to cultivate political rage in black musicians) that I find self-righteous and condescending.

LaDonna and her husband do reflect the difference between working-class Black New Orleans and middle-class Black-Creole New Orleans. Antoine (LaDonna’s ex-husband)and Desiree are also working-class Black New Orleanians. Davis is a white, native New Orleanian who, partially through his music, moves between a mostly white Uptown N.O. and various sects of Black New Orleans. He brings humor to the series. He also shows the interactions of New Orleanians across race and class (although they are less frequently across class than race in reality), often in the context of the music scene in his case, and the complexities therein. The fact is, in New Orleans, there is an openness that crosses race, and to a lesser extent class, to a greater degree than it does in most places in the U.S. That openness leads to sometimes uncomfortable interactions, sometimes humorous and enlightening, sometimes offensive, sometimes violent. I don’t see how any of this lies outside of the “real” New Orleans. The real New Orleans includes all of this and more. True, it focuses largely on the artistic workers in the city. That is part of the point of the show. But it does also show LaDonna’s entrepreneurialism (owning a bar is not exactly art), and the working-class, informal artwork of the Mardi Gras Indians. This is not “high” art. So I don’t quite understand the criticisms expressed here. I am from New Orleans, and live here now, and I think that the series does show many everyday struggles of a variety of people since Katrina – waiting for money to renovate a gutted-out house that someone is camping out in, working in sweaty kitchens of restaurants, scrambling for gigs, trying to represent underdog clients as a lawyer while raising your daughter alone after her father’s suicide. Frankly, I feel the show portrays an impressive variety of people and situations, across race, class, and various interests. It can’t show everything, and would be the worse for trying.

But y’all, Davis’s character is SUPPOSED to be annoying and offensive. Moreover, I don’t think you can portray New Orleans culture in any semblance of authenticity without a white character who exploits and appropriates African American creativity and cultural production. They’ve been there from day one, haven’t they?

I think Davis is a contemporary avatar of the exploiter / connoisseur / record producer who has been a leech on black New Orleans culture from way back. And the audience disdain for him suggests that we now know that is wrong. The scene where he’s trying to get Lil Calliope to listen to Woody Guthrie was the ultimate absurd example of that–and the guy’s reaction was perfect. I don’t get the sense that the show is unaware of what an ass Davis can be; quite the contrary–he is a buffoon much of the time, but not just to annoy us.

That the show paints Davis as a sometime good guy in addition to being annoying and offensive seems, well, authentic. Not all white people who rip(ped) off black artists are evil; some of them truly adore the art and don’t realize the problems inherent in what they’re doing. But it also shows his lack of self-awareness in other areas of his life, and even making a bit of progress in the girlfriend and neighbor relationships. I think of the complexity in Simon’s other “bad” characters–who seem to be placed in the story for us to hate or be annoyed by–such as Hidalgo, and from other shows like Generation Kill and The Wire too.

Davis is also a catalyst for white viewers to comfort ourselves that we are superior to him: more sensitive, more attuned to race and power hierarchies, not as dorky. But I suspect most white folks, at least who grew up in New Orleans, secretly fear that we are actually like Davis, and like him, don’t mean to be and don’t realize it. White New Orleanians’ identity, which is in part defined by our immersion in black culture, is a tricky business.

I remember going to Benny’s Bar on Valence a lot in the mid-80s to see Charmaine Neville, J.D. and the Jammers, the Uptown All-Stars, with other high school kids who were not black. My sense at the time–years before I read bell hooks or did any serious thinking about racism and whiteness–was that I was transgressing into somebody else’s space, where I may or may not be welcome. Behaving with respect, not calling undue attention to ourselves (we were also underage), we felt nothing but contempt for the drunk New York (or New Jersey?) Tulane students who started showing up there more and more. They were exactly what we didn’t want to be: loud, rude, seemingly ignorant of the complexities of the space they were entering and transforming by their entry. So in our disavowal of the arrogant white people, we tried (not entirely successfully) to reassure ourselves that we were not that bad.

This whole comment has been heavily influenced by a dialogue with anthropologist Helen Regis that (yes, it’s true) began at a second line back in March, and continues electronically. She’s got a great article in progress on Davis’s character, which I hope will be published soon.