Could The Good Wife Be More Prescient?

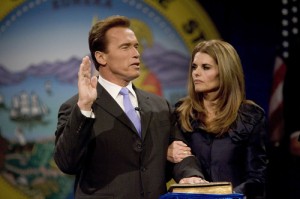

When it comes to misbehaving male politicos, troubled marriages, and suffering wives, it seems a reasonable question to ask whether the writers/creators of The Good Wife are either clairvoyant, or just darned lucky. Over the last weeks, the coincidences between the news and the popular CBS show have been downright eerie, beginning with the announcement that after twenty-five years of marriage, Arnold Schwarzenegger and wife Maria Shriver officially separated. A week after the couple’s parting became public, the LA Times broke the story that over ten years earlier Schwarzenegger fathered a child with a longtime member of his household staff. On the day that The Good Wife closed season two, Schwarzenegger confirmed the veracity of that report.

When it comes to misbehaving male politicos, troubled marriages, and suffering wives, it seems a reasonable question to ask whether the writers/creators of The Good Wife are either clairvoyant, or just darned lucky. Over the last weeks, the coincidences between the news and the popular CBS show have been downright eerie, beginning with the announcement that after twenty-five years of marriage, Arnold Schwarzenegger and wife Maria Shriver officially separated. A week after the couple’s parting became public, the LA Times broke the story that over ten years earlier Schwarzenegger fathered a child with a longtime member of his household staff. On the day that The Good Wife closed season two, Schwarzenegger confirmed the veracity of that report.

Conterminously, attention was being paid to the relationship between marital ethics and political futures in the run up to the Republication presidential primary: hopeful Newt Gingrich is a known adulterer and thrice married, and (yet unannounced candidate) Indiana governor Mitch Daniels is remarried to a woman who previously divorced him and left their four children in order to marry another man.

Finally, the same week of the Shriver/Schwarzenegger bombshell, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the head of the IMF and assumed frontrunner for the French presidency, was jailed after being accused of sexual assault by a housekeeper at an elite Manhattan hotel. His wife, Anne Sinclair, staked his $1 million bail and is reportedly bankrolling his expensive house arrest.

This season of The Good Wife seemingly referenced all this and more (the episode titled “VIP Treatment” literally featured a liberal Nobel Prize winner accused of assaulting a masseuse in a high end hotel), and continues to use both its cases and its characters’ private lives to articulate the myriad intersections of publicity, performance, and pain that comprise political unions. Yet, if season one of The Good Wife was patterned most blatantly after the Spitzer scandal, season two has inadvertently yet presciently refracted through the Schwarzenegger one. Consider the following coincidences between life of the fictitious Alicia Florrick (Julianna Margulies) and the Shriver ordeal: in each, professional women “opted out” of careers in the name of their husbands’ political aspirations (Shriver abandoned a post as an NBC reporter when she became California’s first lady; Alicia previously gave up her career as a lawyer to support her husband’s job as State’s Attorney). Revelations emerged of male misdeeds long in the past but never divulged to the wronged wife (Schwarzenegger’s affair with a household staffer allegedly occurred over a decade ago; Peter’s one night stand with Alicia’s co-worker Kalinda took place before Alicia knew her). An implied association exists between the wife and the “other woman” (Shriver allegedly lived with the female housekeeper who bore her husband’s child; Alicia recently called Kalinda her “best friend”). In the course of contentious campaigns riddled by sexual scandal, both women helped their husbands win by publicly asserting these men’s essential decency (Shriver’s “Remarkable Women Tour” began days before the governor’s recall election; Alicia’s “Hail Mary” interview was televised on the eve of Peter’s bid for reelection as State’s Attorney). Their marital meltdowns were paradoxically both years in coming and vertiginously abrupt (The announcement of the Shriver/Schwarzenegger separation and the revelation of the “love child” came in the course of one week; Alicia packed up Peter’s things and found him a new apartment in the span of one night). Finally, both narratives testify to grief that is less a wife’s than it is a mother’s (Alicia’s only real breakdown occurs when she tells her children that she and Peter have separated; Shriver’s public statement reads, “This is a painful and heartbreaking time. As a mother, my concern is for the children”).

These stories make clear truisms we have long known, particularly that marital sexuality serves as a metric of morality, and that for public figures there are myriad benefits to having a good marriage, and even (if not more) dangers in not. Related is the role that, in a still largely male dominated political arena, wives play in maintaining a requisite image for the men whose lives, campaigns, and children they support. The political stories of the last weeks also throw into relief a reality of marriage that is not unique to politics, particularly the slippery nature of love, loyalty and sexuality. Though the institution of marriage overlays these vagaries with convenient and predictable scripts of enduring fidelity, their far more untidy underlying truths reemerge at moments like these. Yet because marriage frequently registers in our national consciousness only in times of crisis, these conversations do little to furnish us with an adequate vocabulary to talk about real wives and their real world marriages. Instead, sexual scandals slot marriage’s messiness instead into tired scripts that have prevailed in American discourse since at least the nineteenth century wherein upper class women were regarded as the “angels” in the house, the gatekeepers of morality and virtue, in contrast to men corrupted by the supposedly amoral public sphere.

Tales such as the Schwarzenegger/Shriver breakup tempt us, unfortunately, back into similar binaries where “bad husbands” hurt “good wives,” simplistic schemas that tend to disempower the women cast as suffering angels. Yet, it is precisely such well meaning but ultimately damaging mythologies that The Good Wife might help us to resist. As the season finale concluded with the closing of a door to a high end hotel room, where a still-married woman entered with a man who is not her husband, but rather a longtime friend, boss and object of desire, with the promise of nothing more than one hour of “good timing” it became abundantly clear that wife Alicia is, at least, no angel.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YbgfZucQ6k&feature=youtu.be

Thanks for this Suzanne. The Good Wife has really been one of my favorite shows on TV (network AND cable!) since it premiered; I’ve really enjoyed the way it holds up the complexities of marriage, family, & career to interrogate the gendered/classed/raced cultural expectations of such roles and responsibilities, and for the most part, does it well. The timing of the Schwarzenegger and Edwards news stories has certainly made the show seemingly more relevant, but I think one reason the show works so well might be less about prescience and more about history.

While the show was inspired loosely by Spitzer’s coverage/story, his is not exactly a unique case of public infidelity. There have been women struggling with the complexities of life after sex scandals for centuries – we just don’t always get the depth of their stories. To me, Alicia’s such a great character because she’s both a refreshing contemporary figure while also part of a familiar cultural narrative operating in a particular historical moment. LIke you mention, I love the way developments w/ the Governator etc. not only refract onto but also through the narratives in The Good Wife. Glad to know there are others out there appreciating similar elements of the show!

[…] maintain its “quality” status by still garnering critical acclaim for its acting, writing and political timeliness while also maintaining high enough ratings to survive on network […]