Sherlock and the representation of Chineseness

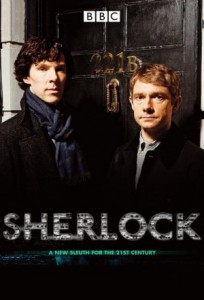

The BBC drama Sherlock received much positive attention when its first season premiered in 2010. Noted for its stylishness, wit, and knowing tone, this contemporary re-envisioning of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective was a critical and commercial success, winning the Best Drama Series BAFTA, and, for the final episode, drawing a combined audience of 7.3 million viewers on BBC1 and BBC HD. It is not difficult to see how this programme fits in with established debates around ‘quality television’ and the BBC’s priorities in the contemporary broadcasting context. Indeed, the phrase ‘worth the license fee alone’ was quick to be invoked in praise of the show. With a second season due to air in early 2012, I think now is a good time to engage in critical reflection, and – much as I enjoy the programme (and I do)–to spoil the sport somewhat.

The BBC drama Sherlock received much positive attention when its first season premiered in 2010. Noted for its stylishness, wit, and knowing tone, this contemporary re-envisioning of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s fictional detective was a critical and commercial success, winning the Best Drama Series BAFTA, and, for the final episode, drawing a combined audience of 7.3 million viewers on BBC1 and BBC HD. It is not difficult to see how this programme fits in with established debates around ‘quality television’ and the BBC’s priorities in the contemporary broadcasting context. Indeed, the phrase ‘worth the license fee alone’ was quick to be invoked in praise of the show. With a second season due to air in early 2012, I think now is a good time to engage in critical reflection, and – much as I enjoy the programme (and I do)–to spoil the sport somewhat.

Now, my concern isn’t actually that, the BBC license fee by itself doesn’t, of course, pay for the programme, which is co-produced by PBS’s WGBH Masterpiece series in the USA–much (if not all) contemporary high-end British drama has overseas funding. What concerns me about the close links made between the programme and the BBC’s status as a public service broadcaster relates to something else, namely the problematic politics of representation in the second episode “The Blind Banker”. In this episode, Holmes and Watson investigate a break-in and uncover a Chinese crime syndicate. The representation of Chineseness in the episode hinged on tea ceremonies, sinister villains, calligraphy and circus performers doing uncanny tricks.

Yes, these stereotypical notions of Chineseness need to be understood in the context of the discourses of heritage and tourism that pervade the text, running alongside similarly stereotypical, export-friendly notions of Britishness. And, indeed, these stereotypes can be understood in relation to issues of performance: the tea ceremony is performed by a curator, and the escapology and acrobatics acts are performed by a touring circus. Indeed, with the emphasis on the staging of these moments, of a performance taking place for visitors, a certain performative quality is present, which undercuts the stereotypes somewhat. However, in a text so concerned with updating the Victorian source material to the contemporary period, there is very little else to the representation of Chineseness; it seems that Sherlock Holmes can use SMS messaging and GPS tracking, but Chinese culture is rendered remarkably narrow via such reductive stereotypes.

The final showdown with the gangsters is especially concerning here: while there is still some performativity, there is also an unnecessarily overelaborate scenario, where the gangsters prefer a big crossbow to a handgun when extracting information out of Watson. There is a noticeable sense of pastness pervading Chinese culture: whilst the Chinese characters use contemporary technology such as mobile phones, they are most closely aligned to the past, preferring ancient arbalests to contemporary weaponry and regularly finding time to engage in a spot of origami-making. Interestingly, during the showdown, it seems these professional criminals need to be told about the danger of using a handgun in a tunnel, where bullets could ricochet off the walls. And they are told by Holmes, emphatically presented as master of contemporary technology; while the female syndicate boss is eventually killed when using a laptop, in some laser high-tech fashion I don’t understand. Holmes is the superior mind, the white man of intellect and rationality, and science; the Chinese characters are primarily present in terms of their bodily physicality. The politics of representation become dubious, moving towards an ornamental, exotic, Orientalist Other, and a notion of China as somehow located within pastness, outside of historical evolution and Western modernity, that has run through Western discourses, most famously perhaps Hegel’s 1840 Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte.

The question remains whether the use of such obvious clichés is meant to be understood as part of the text’s ironic knowingness. This line of argument could be supported by the fact that Sherlock’s co-creator Mark Gatiss, who plays Mycroft Holmes, had previously starred in a Fu Manchu-parodying episode from 2001’s Dr. Terrible’s House of Horrible. However, what strikes me about Sherlock is that, in a text so preoccupied with ironic playfulness, in which knowing jokes about the homosexual subtext between Holmes and Watson abound, I find no ironic commentary about the representational clichés concerning Chinese culture forthcoming, when, surely, the final showdown is begging for Holmes or Watson to make a quip about the presence of the cumbersome crossbow. I’m not saying that such ironic self-reflexive commentary would necessarily render the representational clichés acceptable, but it’s simply not there. There is a tension in this text, in which knowing playfulness sits side-by-side with representational clichés that are presented in a noticeably serious frame.

Sherlock is marked by some problematic representational strategies that are not absolute, but certainly present enough to be troubling. I think one reason for the inclusion of these representational clichés is that they are undeniably stylish. Indeed, when taking the screen shots for this post, I was reminded (not that I needed to) of John T. Caldwell’s concept of televisuality by the fact that nearly every frame looks fantastic. Sherlock is a troubling sign that a public service broadcaster such as the BBC could be shifting away from a sensitivity toward representational matters, preoccupied with the importance of developing distinct visual brands.

Sherlock is marked by some problematic representational strategies that are not absolute, but certainly present enough to be troubling. I think one reason for the inclusion of these representational clichés is that they are undeniably stylish. Indeed, when taking the screen shots for this post, I was reminded (not that I needed to) of John T. Caldwell’s concept of televisuality by the fact that nearly every frame looks fantastic. Sherlock is a troubling sign that a public service broadcaster such as the BBC could be shifting away from a sensitivity toward representational matters, preoccupied with the importance of developing distinct visual brands.

And this shift seems to be echoed in mainstream public discourse, where reviews of the series in the British national press were also preoccupied with the stylishness of the show, making no mention of the representational issues I have been exploring (with blogger Laurie Penny being a rare exception), and the question remains what the response would have been if troubling imagery relating to a different national, ethnic or minority group had been used. Certainly, with the current pressures on the BBC, the phrase ‘worth the license fee alone’ is only likely to become more pressing, and in need of critical reflection.

Astute observation here. Somebody had to say this.

Same old story, innit! White people remain dismissive—and willfully ignorant—of other people’s cultures. For one example, I am fairly sure origami is a Japanese art, not Chinese! Thirty seconds spent on Wikipedia could have told them that.

I suppose the professionals in the television industry—who should know better and probably do—feel they must pander to the lumpenproletariat’s ignorance using such cheap shots. As you observed, these are essentialist and subtly demeaning stereotypes that usually imply that “they” are not as smart as “we” are.

Ironically, “we” are nowhere near as smart as “we” think we are! It’s just pathetic, really!

Hi Michael,

Thanks – and your comment that ‘somebody had to say this’ is particularly interesting to me, in light of my reference to feeling compelled to ‘spoiling the sport’. I’m quite intrigued by my own initial hesitation to articulate the problematic politics of representation in what is otherwise a show that I much enjoy – but the more I engaged with the episode, the more I couldn’t not address these problems. Why is it that not ‘more bodies are saying this’? (and here i include the national press, which made no single mention of any of this, as far as I can tell) – what do you think?

Simone

I think it boils down to pandering to the popular hunger for stereotypes–stereotypes make ordinary people feel superior to Others. This is common here in the US because the revenues of the networks depend on ratings, and they will use any cheap shot they can to boost ratings (even PBS, sadly). However, one would expect the people who run the BBC to know better than to sink to this level. Apparently the Beeb has been dragged into a ratings competition with the commercial networks, and they are all engaged in a race to the bottom.

I’m a bit shocked that this is being taken so casually by the cognoscenti and that you seem to be the only observer pointing a finger at this. Kudos to you!

Yes, when it comes to the BBC, there are certain kinds of expectations as to the drama it produces and broadcasts. But as British broadcasting has shifted from public service towards a free-market model, the BBC has to play the commercial game in public service’s clothing, now more than ever… so my boo goes to the deregulation of British broadcasting!

A well rounded overview of the problems inherent in this episode.

Whilst episodes one and three of ‘Sherlock’ updated the notion of Holmes and his world in an extremely convincing fashion, this episode’s attitude to Chinese characters and blatant embracing of cultural clichés seemed stuck way back in the era of Boys Own adventures and inscrutable Oriental fiends.

It’s worth pointing out however, that the episode in question was written not by Mark Gatiss or series co-creator Stephen Moffat, but by Stephen Thompson.

Dear Graham,

Thanks very much. You’re absolutely right; it is important to point out that the episode was written by Thompson – authorship was something I couldn’t get into in as much detail as I would have liked.

Of course, the series was explicitly promoted (and subsequently received) via the figures of Gatiss and (especially) Moffat, and I wonder why they didn’t pick up on these blatant cliches; or if they did, why the cliches remained. Surely, they have enough experience in comedy to have been able to do something about what’s going on in this episode? I am honestly baffled about the episode’s noticeable drop in textual sophistication. Can’t wait to see what the second season will bring!

Simone

Gatiss and Moffat SHOULD know better–and apparently they do, seeing as how, as you point out, their work is usually free from this sort of cheap gambit. Allowing these to slip by demonstrates a lack of judgement on their part, an they should be called to account. Maybe this blog will accomplish that. And boo to Stephen Thompson!