Playing Like a Girl: Feminist Praxis as Feminist Pragmatics

Rolling Stone magazine just issued, seemingly for the umpteenth time, a list of the “100 best rock guitarists.” Jimi Hendrix, of course, topped the list. Very few names from after the 1970s made it at all. Women didn’t show up until #75, Joni Mitchell, and #89, Bonnie Raitt. This doesn’t matter, right? Rolling Stone isn’t taken seriously by any music aficionado worth her or his vinyl record collection, and hasn’t been since, say, 1972. Even so, its list of “100 Greatest Guitarists” will filter through other mainstream media outlets, once again reinforcing rock music as a masculine space. Which makes it even more horrible that June Millington isn’t on the list.

Rolling Stone magazine just issued, seemingly for the umpteenth time, a list of the “100 best rock guitarists.” Jimi Hendrix, of course, topped the list. Very few names from after the 1970s made it at all. Women didn’t show up until #75, Joni Mitchell, and #89, Bonnie Raitt. This doesn’t matter, right? Rolling Stone isn’t taken seriously by any music aficionado worth her or his vinyl record collection, and hasn’t been since, say, 1972. Even so, its list of “100 Greatest Guitarists” will filter through other mainstream media outlets, once again reinforcing rock music as a masculine space. Which makes it even more horrible that June Millington isn’t on the list.

Who is June Millington? To start, she’s a lead guitarist who wields a mean Les Paul. Filipino-American Millington, and her sister Jean, a bassist, started what would become the group Fanny, a group still known to few, while in high school in Sacramento in the 1960s. Fanny was the second female group ever signed to a major label, scoring a contract with Reprise Records, an imprint of Warner Brothers during the period when it was the hottest rock label going. Fanny achieved chart success with “Charity Ball” in 1971, and recorded their third album, Fanny Hill, at Apple Studios in London. They worked with such esteemed produced as Richard Perry and Geoff Emerick, better known as the engineer on many Beatles’ albums. After she left Fanny, June Millington went on to be a founding mother of the Women’s Music movement of the 1970s.

June Millington’s most significant achievement is something else that few have heard of. Twenty-five years ago, Millington and her life partner Ann Hackler founded the Institute for Musical Arts (IMA), “a nonprofit teaching, performing and recording facility supporting women and girls in music-related businesses.” (1) Originally located in Bodega, California, IMA is now located in Goshen, Massachusetts on a 25-acre property outside of Northampton, Massachusetts. IMA, described by Hackler as “the love child of an educational activist and a rocker,” (2) provides performance space for concerts by established musicians, residential summer camps for girls who range from pre-teens through college, and a state-of-the-art recording studio.

Hackler is a long-time social activist who was running Hampshire College’s Women’s Center when she first met Millington in 1981. Millington was not an activist like Hackler, but was very attuned to the limitations of the music industry for women, and to the empowering possibilities of playing in a band with other women. For Millington, musicianship was key, as well as understanding and having access to the recording studio.

2002 saw the first of IMA’s summer rock and roll camps for girls. The program has now grown to several camps a summer, including a studio intensive for older teens. (Full disclosure: my 13-year-old daughter attended one of the teen sessions this summer.) Parents, even those who study and write about gender and popular music for a living (ahem), are banned from the grounds until the final concert. The girls live together in yurts or bunk in the barn/performance space/recording studio, take lessons, and have access to all of the instruments and many of the teachers, including Millington, throughout the day and night. They learn, among other things, how to run a sound system, how to write and arrange music, how to record, engineer, and mix, how to collaborate as members of a band; how to write songs, how to run a band rehearsal, and more. That is, what young men learn when they start bands in their early teens (3). Several ex-campers are now pursuing careers in their own right. One, Sonya Kitchell, toured with Joni Mitchell.

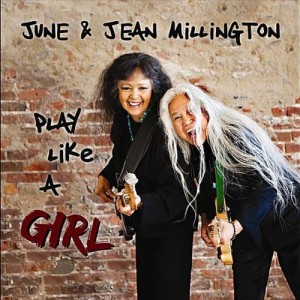

Inspired by her work with the camp, June and Jean Millington, along with Jean’s son, drummer Lee Madeloni, recorded and released a new album, Play Like A Girl, earlier this summer. A Kickstarter campaign brought in enough donations to take it on the road. The title song includes the voices of campers, and a few performed with the Millington sisters on the road. They also took their pedagogy along, holding workshops for girls when possible.

IMA is motivated by, in Hackler’s words, a lesbian-feminist analysis (4). Hackler’s analysis may stem from a second-wave feminist foundation, but steers away from the excesses of identity politics while incorporating strong elements of multiculturalism and other elements more associated with the so-called third wave of feminist theory. Most of all, IMA’s work is feminist praxis as feminist pragmatics. Rather than focusing too much on getting the name of the theory right and articulating it to a particular wave or generation, Millington and Hackler forged a solution to a problem: teach girls the tools that will help them make it in the music industry, let them have at it, and have a lot of fun while doing it. So far, it seems to be working. Perhaps there’s a lesson in this for all of our pedagogy.

1. IMA website, http://www.ima.org/home.html

2. “Women in Industry #11: Ann Hackler,” Wears the Trousers, http://wearsthetrousers.com/2011/08/wii-11-ann-hackler/, retrieved 11/28/11.

3. Mary Ann Clawson, “Masculinity and Skill Acquisition in the Adolescent Rock Band,” Popular Music (1999), 18: pp. 99-114.

4. Conversation with the author in the IMA kitchen, July 17, 2011.

A clarification: June Millington was not a founding member of the Women’s Music movement, but did contribute to the album that first drew a lot of attention to it, Cris Williamson’s The Changer and the Change. I originally had that in but lost the nuance when I edited my draft down to a reasonable size.

[…] Music Geek pointed me to this excellent article about June Millington. I had never heard of her before, and she is excellent. Check out the […]

[…] Music Geek pointed me to this excellent article about June Millington. I had never heard of her or Fanny before, so I obviously owe a debt. Check […]