Compulsory Ultrasound Audiences and Feminism

Earlier this week, Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell withdrew support for a bill that would require women seeking abortions to undergo transvaginal ultrasounds. McDonnell backed down due to public outrage over the idea that the GOP (you know, the party who don’t like government intervention in people’s lives … only their vaginas) felt it had the right to enforce a medically unnecessary, highly invasive procedure that is somewhat akin to state-sanctioned rape, and that – hypocritically for a proposal from the party opposed to state healthcare – turns doctors into servants of the state before they are servants of their patients. McDonnell stepping away from the bill might sound like a victory for rationality, but it’s hardly a resounding one, as the bill seems fated to end up looking like several other ultrasound laws, “only” requiring an external, abdominal ultrasound.

Given the disgusting and very literal invasion of women’s bodies that this bill represents, it may seem somewhat crass and/or beside the point to use the ultrasound bill to discuss audience theory, but as I’ll argue, what this bill and its abdominal-only brethren say about women as audiences and as citizens is every bit as disturbing as the acts of physical invasion that have justifiably come under fire. Virginia’s Republican Party didn’t seem to care about the means (the ultrasound), only the ends (women as audiences of ultrasound pics), but those ends require as much criticism as the repulsive means.

Advocates of such bills argue that the ultrasound will offer a woman “more information” so that she can make “a reasoned choice,” but what they’re clearly relying on is the idea that when a woman sees a picture of the fetus, she will fall in love with it, maternal instincts will magically kick in, and she’ll now see it as a human being that needs her protection and a “Mommy’s Sweetie” layette from Babies ‘R’ Us. This is a remarkably naïve notion of how audiences work. Or, rather, it’s third person effects in operation, wherein one’s own reaction to an item of media is trusted to be sophisticated, whereas a worried-about other’s is not. Here, women are imagined to be that third person (itself posting the normative “us” as men), and to be a simpler audience, one whose hormones and feminine frailty lead to having more reliably passive, simplistic, and easily-engineered responses to media.

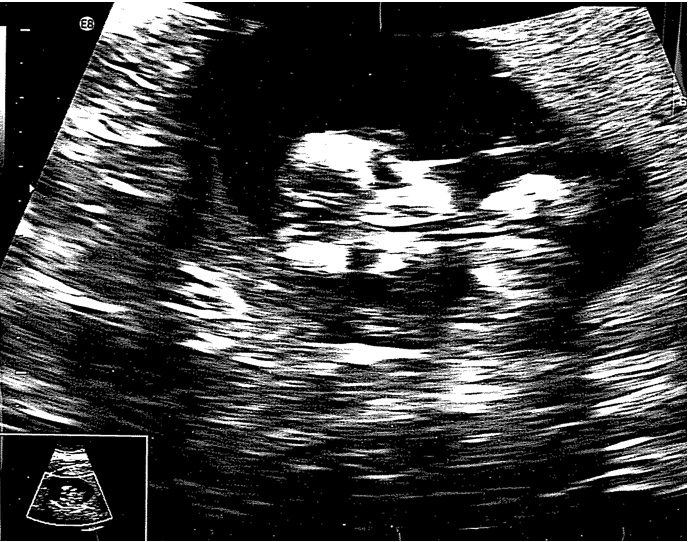

Let’s get something straight, though: ultrasounds don’t necessarily make a fetus look all that human-like. Here’s an example (published with approval of the mother):

Now, maybe your Rorschach-reading skills are better than mine, or maybe you’re more adoring of all things baby, and you therefore look at the above picture and see a cute little baby. Personally, it looks like an alien to me. Republican ultrasound bills believe, though, that women will all be overcome by the babyness of such images, and they don’t consider that maybe a woman will look at such a picture and think of her fetus as even less of a human being, as intruding and unwanted.

The bill therefore seems as well-considered as might one that requires women seeking abortions to read a poem from a Hallmark New Baby card (“Babies are a blessing …”). Or perhaps anyone seeking a divorce will soon need first to attend statewide viewing sessions of When Harry Met Sally? Or maybe Gitmo will soon start a program of showing photos of happy picnicking families with Labrador puppies to suspected terrorists as a way to “turn” them.

But the bills don’t just betray a belief in women as simple audiences; they go a step further in encouraging the state to take advantage of the supposedly doltish female audience and engineer their responses. The Virginia bill came under heavy fire (as it should have) because of how physically invasive it was. But behind all the ultrasound bills is the idea that the government could or should determine and design women’s media exposure, not simply in the tried-and-true fashion of censoring this or that, but by dictating that they must look at certain images. Welcome to Clockwork Orange. Programs for drunk drivers and others found guilty of certain crimes have long paved a path of requiring audiencehood, but we’re seeing an expansion of said path to allow for forced media consumption by those whose life choices worry the state. The notion behind such bills is that the state will determine what media women need to watch, listen to, or look at (once again, by the party that says it doesn’t like government involvement in people’s lives).

But the bills don’t just betray a belief in women as simple audiences; they go a step further in encouraging the state to take advantage of the supposedly doltish female audience and engineer their responses. The Virginia bill came under heavy fire (as it should have) because of how physically invasive it was. But behind all the ultrasound bills is the idea that the government could or should determine and design women’s media exposure, not simply in the tried-and-true fashion of censoring this or that, but by dictating that they must look at certain images. Welcome to Clockwork Orange. Programs for drunk drivers and others found guilty of certain crimes have long paved a path of requiring audiencehood, but we’re seeing an expansion of said path to allow for forced media consumption by those whose life choices worry the state. The notion behind such bills is that the state will determine what media women need to watch, listen to, or look at (once again, by the party that says it doesn’t like government involvement in people’s lives).

In doing so, the bills attempt to stigmatize behavior that isn’t illegal, but that the GOP would like to see as illegal, thereby creating a second tier of citizens who haven’t actually violated any standing law but whose current actions supposedly require monitoring and then disciplining through media exposure. They tell us that one group of citizens needs extra surveillance and attention. No surprise, given the misogyny of many other bills and statements of late, that this group is women (as rendered clear by bills designed satirically to instead put men in the cross-hairs, such as a Georgian proposal to criminalize vasectomies, for instance, or another that would require that men seeking Viagra be subjected to prostate exams). And thus while the conception of how state, media, female audience member, and citizen are related that undergirds this bill may seem of less immediate importance to us as feminists than the invasive nature of the procedure, I’d pose that this conception needs as much resistance and criticism inasmuch as it opens up yet more ways to legalize women’s inferior status. The belief in the passive audience isn’t “just” a theory – here it’s become the precept to repressive policy.

You might be giving the GOP more credit for actually thinking about the media effects of seeing such images. To me, it seems like another in a string of policies that try to make abortions harder for women to obtain – more expensive, more time-consuming, more moments of decision-making, and more opportunities for feel that health care workers are judging you. I don’t think they really imagine that a pregnant woman looking for an abortion will have a true change of heart by falling in love with the ultrasound (although that might work as a rationalization for the bill), but that by making the process harder, more pathologized, and more shame-inducing, women will stick to what seems easier in the short term by having the baby. I think the way they most undercut these imagined women’s psychology is not through media effects, but by assuming that getting an abortion is an “easy” decision for anyone to make.

I’m sure you’re right about the desire to make it harder. But this specific method still relies upon an assumption that women are dolt audiences and/or likely to react affectively to the image (even if those behind the bill don’t really believe in that, as you say). Imagine, for instance, if men were required to look at medical imaging of their sperm before getting a vasectomy.

I think Jonathan’s analysis of how women are assumed to behave as audience is really interesting and likely right, although clearly disconnected from how many women actually behave. However, the bill oddly seems to align with Jason’s understanding of things a bit better because it does not actually require the woman to LOOK at the ultrasound, or hear the fetal heartbeat, only to undergo the procedure. I can’t speak for all women everywhere but I can’t imagine that I would take the option to look at the image or hear the heartbeat if I had decided to have an abortion. I have had female friends who are on the fence who have elected to do both as part of their decision making process, since the ultrasound is almost always available as an option. Given the many women who can just scrape up enough money to do the procedure making them pay for this as well is a very practical roadblock to an abortion, as is the 24 hour waiting period attached to it given many womens inflexible work schedules and sometimes overbooked abortion providers. The fact that at the end of the day the bill requires that the image be made available but not consumed is particularly interesting to me. Instead we have a situation in which women’s bodies are forcibly recruited into producing a form of media that they do not want and likely will not consume, I am not sure what the media frame is for that.

But all too often, Kyra, you can’t separate the image and the procedure. Ultrasounds rooms have a screen poised right above the bed for the woman to see. And there’s an aural aspect here, too, as the heartbeat is turned on automatically. These are things a woman would need to opt out of quite actively — certainly, my wife and I were never asked if we wanted the screen on or the heartbeat on, as it was simply put on. So I think there’s still an assumption of audiencehood, even if it can be resisted through knowing what to ask for.

That point makes a lot of sense to me Jonathan and actually brings in another point that I think nicely intersects with your audience. The issue, largely neglected in the bill, of viewing context and the impact of the ultrasound image provider. When a hospital, erroneously, feared I had an eptopic pregnancy they automatically turned the screen away and turned off ye heartbeat sound without me asking. In their own, slightly paternalistic, way that had established a set of viewing and non viewing contexts that were based on their own audience assumptions. This emphasis on context may in the end lead to a fair amount of non viewing but also may support your larger point.

According to this article http://timesdaily.com/stories/Ultrasounds-before-abortions,187883, Alabama has a similar bill in the works, and the chairman of the committee that approved it (who, by the way, owns a company that sells ultrasound machines) says he thinks the bill is needed because it will help “a mother to understand that a live baby is inside her body.” The women don’t have to look at the ultrasound images, but the doctor has to describe them to her. (?!) And this, on the bill’s sponsor: “Scofield said he hopes that, if signed into law, his bill will stop some abortions. Though the bill states a woman can look away from the ultrasound image, Scofield wants her to see it.“So she sees that this is not just a clump of cells as she is told,” he said. “She will see the shape of the infant. And hopefully, she will choose to keep the child.””

Hey- I’m wondering about the indexicality of these kinds of images, and the emotional impact there? I know that women aren’t dumb (oh, wait, maybe I am??!! 🙂 but I feel like what the GOP is counting on here is the troubling encounter between image and the sensation of either being invaded by the wand of the trans-vaginal ultrasound, or the equally physical though less invasive experience of the jelly-on-the-belly ultrasound. I feel like rather than focusing on the poor image quality, I would suggest that where the GOP might get women (who are certainly not excited to “kill babies” or be viewed as “unmotherly” in a society that makes motherhood a valued asset even of stardom) is by the indexical “proof” that something is living inside them, even an alien, and were they to terminate, they would be killing it. Without this physical knowledge the decision to terminate may not be easier, but it won’t involve having to look your victim in the eye.

I dont understand why this is a political issue and not a private, personal, medical matter. Many OB-GYN’s use newer transvaginal ultrasounds because it give them better imaging of the entire reproductive system. One can opt not to. It just seems like if an MD prefers this to get better images, to know the positioning of the uterus (often tilted), know where the tiny fetus is exactly to minimize incomplete procedures or complication, that the discussion should be between the patient & Dr., and no one else. There is also the cases of women wanting to see the ultrasound even knowing she will not be keeping it for whatever reason. I don’t hold judgement on wanting to see or not see it, just want the government to stop making personal, medical decisions for people when they should instead focus on facilitating options, information, and good, available care to everyone.