Gazes, Pleasure, and the Failure of Magic Mike

When I saw the first bit of promotional material for Magic Mike, it took me about two seconds to call my mother. A movie about male strippers, featuring Matthew McConaughey and Matt Bomer? It was as if someone had reached into my mom’s brain, pulled out her id, and made it into a film. And as more and more trailers, stills, and interviews hit the internet, TV screens, and magazine pages, I became more and more excited about what seemed to be a viable summer popcorn movie focused almost entirely on the (straight) female gaze.

When I saw the first bit of promotional material for Magic Mike, it took me about two seconds to call my mother. A movie about male strippers, featuring Matthew McConaughey and Matt Bomer? It was as if someone had reached into my mom’s brain, pulled out her id, and made it into a film. And as more and more trailers, stills, and interviews hit the internet, TV screens, and magazine pages, I became more and more excited about what seemed to be a viable summer popcorn movie focused almost entirely on the (straight) female gaze.

I saw Magic Mike on Monday night, with my mother, in a theater exclusively populated by cheering, hooting, unabashedly lustful women. The movie’s marketing had obviously hit its target. And yet, the film’s resolution turned out to be a bit of a bait-and-switch, promoting the idea that smart, attractive, morally sound women would never enjoy, or even sanction, male stripping. In other words, the film’s overarching message is a reprimand and a ridicule of the very women whose money it so desperately seeks.

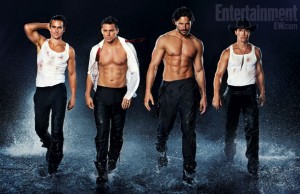

While the film’s protagonists are all male, Magic Mike features many female characters. Unfortunately, most of them fall into one of two categories: sexually-promiscuous, exploitatively filmed, usually topless hangers-on of the male strippers who both literally and metaphorically represent the protagonists’ downfall, and attendees of the male revue who are portrayed as either drunken, childish floozies or desperate, unattractive objects of ridicule. (In one particularly distasteful scene, Joe Manganiello’s stripper character, “Big Dick Richie,” mockingly mimes back pain after lifting a heavyset woman, which seems like a poor business strategy for a man of his profession.)

The exceptions to this category are Olivia Munn’s Joanna, a bisexual, promiscuous psychology student who cruelly leads on Channing Tatum’s titular character; and Cody Horn’s Brooke, a responsible medical assistant and Mike’s ultimate love interest, who doesn’t approve of Mike or her brother (Adam, played by Alex Pettyfer) stripping. Of all the characters, Brooke is the one we’re asked to identify with and see as the moral center of the story. She has a “real” job, she doesn’t give in to Joanna’s scandalous advances, she never drinks or does drugs, she’s her brother’s primary caretaker, and she acts as the catalyst for Mike to realize that his stripping is immature at best and destructive at worst. By the end of the film, Mike has quit his job to focus on more mature pursuits, and Brooke rewards him by finally relenting to his romantic interest. (Unlike the usual gender-flipped stripper narrative, there is no indication that Brooke is attempting to “save” Mike’s virtue, or seeking to claim sole ownership of his naked body; it is, rather, her female virtue she is protecting when she refuses to associate with male strippers.)

There are more problems with this film: the insistent reinforcement of the male strippers’ heterosexuality coupled with mild instances of homophobia (only the morally suspect Joanna is allowed to be textually queer); the lack of characters of color who aren’t drug dealers (other than Joanna and Tito, Adam Rodriguez’s almost dialogue-free stripper character); and the fact that Brooke does nothing more than flail and scream when her brother nearly overdoses, despite her established medical training. But all of these issues tie into the same fundamental flaw: though the movie claims to be (and was certainly marketed to be) a film all about flipping sexist tropes and celebrating the female gaze, it can’t help falling back into problematic mainstream patterns: the male gaze, virgin/whore dichotomies, and the vilification of female pleasure.

Yet as I think back on my experience in that movie theater, I can’t help hoping that this is a sign of better things to come. Despite the film’s abundant flaws, Magic Mike has given women (including my mother and, let’s be honest, myself) the opportunity to go to a public, non-stigmatized place (unlike the private home party or derided strip club) to take in the sight of men putting themselves on sexual display for their benefit. The women in the diegetic audience of the strippers’ performances may be ridiculed, but it is still their hungry gaze we are invited to claim as our own. Magic Mike is not a great movie, but I hold out hope that its attempts to break the mold, however halfhearted, will inspire more and better versions of its kind in years to come.

Returning to this piece after seeing the film, I want to raise a few points before Antenna’s spam filter shuts down the comments:

1) Perhaps I am misremembering the scene, but I thought Ritchie *did* experience back pain during that sequence, making it an instance of “reality” invading the fantasy – something the film is invested in more broadly – rather than a bit of vicious comedy.

2) I’m not quite convinced by the notion that Mike eventually believes stripping to be immature, nor did I necessarily read the ending of the film as Mike’s rejection of stripping so much as the specific circumstances of the move to Miami (and, for the sake of an eventual sequel, it’s entirely possible he keeps stripping in Tampa given the nature of his conversation with Brooke).

For me, Adam’s self-destructive behavior served as a preview of what the larger market of Miami would offer, and Mike – whose involvement in stripping was framed as both personal empowerment and entrepreneurial investment – seemed to believe the drug-fueled mess tied to the former would no longer be worth the latter (not to mention his cut was reduced from his initial conversations with Dallas, a betrayal that felt more formative in those final moments than a rejection of the act of stripping itself).

On this level, I’m not sure the film vilifies stripping and the people who partake in it – Dallas’ reclamation of his stripper identity after years of hosting is largely received as a triumphant return (albeit laced with a degree of critical attention to his willful ignorance to Tarzan’s breakdowns that push Adam onstage, or Adam’s downward spiral), and Adam’s integration into the show in Mike’s absence is framed as tragic but less for his profession and more for its personal consequences.

The film’s relationship with stripping is messy, no doubt – I might believe that Brooke’s resistance to Mike has less to do with the act of stripping than it does the lifestyle that comes with it, but I can’t disconnect the two, and your reading is certainly valid. I just ended up finding the film’s counter-narratives of “Stripper becoming disillusioned with the business” and “Man reassessing what he wants to do with his life amidst a difficult financial climate” to render the question more of a gray area than you’re arguing here.