Dark Knight Myths and Meanings

[warning: contains mild spoilers] I watched Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises three times in 50 hours, between Wednesday 18 and Friday 20 July. I first watched it more as a fan – with nervous anticipation, hoping it wouldn’t disappoint – then with a Thursday night crowd, testing and distrusting my first impressions – and finally, brought fan-scholarship to bear for the third viewing, with a notebook out in the dark. I scribbled about 5000 words during that screening, and it was my most rewarding experience of the three.

[warning: contains mild spoilers] I watched Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises three times in 50 hours, between Wednesday 18 and Friday 20 July. I first watched it more as a fan – with nervous anticipation, hoping it wouldn’t disappoint – then with a Thursday night crowd, testing and distrusting my first impressions – and finally, brought fan-scholarship to bear for the third viewing, with a notebook out in the dark. I scribbled about 5000 words during that screening, and it was my most rewarding experience of the three.

On the way out of the theater on Friday morning, I received a text telling me about the events in Denver. And suddenly talking about Batman didn’t seem fun anymore.

As The Onion immediately pointed out, our responses to tragedies are sadly predictable. Right-wing media sources seek cause-and-effect connections between real life and popular texts, delving back to find a single page in a Batman comic from 1986 that bears tenuous similarities to Friday’s news: ironically, at these times they choose to take popular culture seriously, and dig into its archive as tenaciously as any fan or scholar.

Internet communities also respond according to expected patterns. Batman fans craft posters and sigils with images of fallen Waynes, black cowls and memorial ribbons. 4chan cracks morbid jokes, with the disingenuous tag “too soon?”

Of course, it is “too soon” for those jokes – it will never be time for those jokes. It’s also too soon for those cause-effect conclusions – and again, perhaps they will never be valid. But it’s also too soon for the theories that were emerging before Friday’s events – the quick, pat arguments that Batman is a Conservative Crusader or that Nolan’s movie is an “audaciously capitalist vision” that celebrates the “wish-fulfilment of the wealthy.” It’s too soon, as I announced last Thursday (again, perhaps too soon) to call The Dark Knight Rises for one political side or another, to read it as a clear propaganda message. Four years on, Nolan’s previous instalment, The Dark Knight, still offers no straight answers about the “war on terror.”

So it’s too soon to write anything conclusive about The Dark Knight Rises. Perhaps it’s a cynical film, engaging with topical, real-world issues but side-stepping in the final reel for a story about personal heroics, offering fantastical solutions to a contemporary dilemma; and perhaps the same could be said of its predecessor. Perhaps it’s just a complex film, admirably refusing easy solutions.

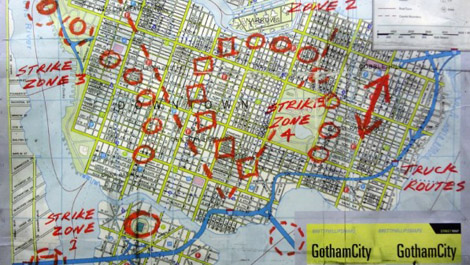

If the movie has a key image, it’s not the tattered American flags or the exploding football field. It’s an image that circulated in viral marketing months before the film’s release – Bane’s “strike zones,” circled on a map of Gotham City.

The package, sent out to key websites in December 2011, reappeared in the Dark Knight Rises, as Detective John Blake studied it for clues.

“I don’t know anything about civil engineering,” he protested. His boss, Jim Gordon, reassured him. “But you know about patterns.”

The Dark Knight Rises – in fact, the Dark Knight Trilogy – is about patterns. It’s about networks. It’s about matrices, links, dialogues, nodes on a map. It’s about echoes between those terms, and the way those terms define themselves in relation to each other, and can shift, and change places. It’s not just as a comment on capitalism that Bane’s men raid a stock exchange, and Bruce ponders the trades they were making.

Just as Batman Begins suggested, more modestly, that Scarecrow’s use of fear as a weapon was no different from Batman’s modus operandi, and The Dark Knight ramped up the stakes by asking what, if anything, separated Batman’s counter-terror measures from Joker’s terror, so Dark Knight Rises is about the fragility of definitions, the limits of structures, the illusion of binary oppositions.

Bane, “born and raised in hell on earth,” becomes a general, and is then revealed as a bodyguard. The chant we associate with him becomes Bruce’s, as he rises from the pit. Bruce, born to privilege in the Regency room of Wayne Manor, falls and is free to remake himself as a nomad, a no-man. Selina Kyle, haunted by her history, lives in a “walk-up” in the Old Town and glimpses liberty when Bruce flies her above the city’s highest levels. Blake tosses his police badge. Talia reinvents herself as Miranda Tate; Bruce and Selina seem to earn a clean slate, but the final shots show that no reboot can wipe the slate entirely clean, and that traces of the old life always remain, just as Nolan’s Batman could never repress Burton’s, Schumacher’s, or Adam West’s (but instead, sometimes seems to embrace and incorporate those earlier versions).

The Dark Knight Trilogy is about myth and meaning, and the way an idea can survive beyond an individual; it tells us there are different ways to live on after death. It may still be too soon to find any message for those affected by the Colorado shootings; instead of reaching for conclusions, perhaps now is the time to simply remember those people like us who went to the movies last week.