Mediating the Past: Radiolab Revisits the Crossroads

**This post is part of our series, Mediating the Past, which focuses on how history is produced, constructed, distributed, branded and received through various media.

**This post is part of our series, Mediating the Past, which focuses on how history is produced, constructed, distributed, branded and received through various media.

The Radiolab episode “Crossroads” aired on April 16, 2012 and exemplified how this public radio program uses sound to explore the past for listeners. Radiolab has won numerous awards, has a significant audience, and is on tour this fall around the country. It is thus an important site where listeners interact with narratives about our history, one of the many subjects Radiolab engages with. Radiolab is a program structured around curiosity, and explores familiar issues from a new perspective. We hear this in “Crossroads,” as Radiolab explores the cultural myths that surround the successful and mysterious blues musician Robert Johnson going down to the crossroads in the 1920s and selling his soul to the devil for the talent to play the guitar.

Oh Brother Where Art Thou's Tommy Johnson sold his soul to the devil for guitar talents--a story reminiscent of Robert Johnson's legend.

This is not a current event story, not breaking news, but an issue that digs at the myths and material traces related to Johnson, myths that have pervaded our culture for the last century. It can be heard on Cream’s “Crossroads” or seen in the Coen Brothers’ Oh Brother Where Art Thou. Radiolab mixes actuality sound (sound recorded outside of the studio on location) with new interviews, archived interviews, and music, around the voices of co-hosts Jad Abumrad and Robert Krulwich. All of these components overlap and function together as Radiolab becomes an academic investigation, an artful montage of sounds, and an informal fireside chat. Thus, Radiolab blurs the line between reality and art to tell a story that will pique listeners’ interest in cultural history, a topic with the potential to get boring.

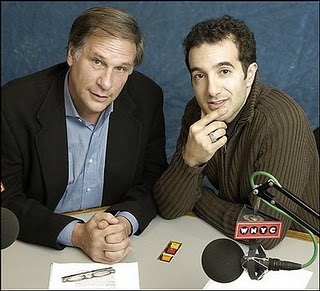

One of the key elements of the show is the dialogue between co-hosts Abumrad and Krulwich. They intentionally use an informal, conversational style to get listeners interested and engaged. Scripted and edited before the show airs, their “natural” discussions invite the listener to feel at ease. Their dialogue also functions in another way, as Abumrad usually tells a story or explains some phenomenon and Krulwich–a stand-in for the audience–asks questions and tries to make sense of what Abumrad is saying. Krulwich’s questions are absolutely scripted, but sound as if they come up spontaneously in conversation.

The infamous crossroads in Clarksdale, MI, which Abumrad tells us is now a tourist attraction.

We hear this at the beginning of “Crossroads” as Abumrad begins to tell Krulwich about his recent trip to the crossroads at midnight and meet the devil. Before he does, we hear actuality noise of the car and the wind as Abumrad talks with someone named Pat and admits that he “is starting to regret doing this.” He then tells us Pat turned off the headlights to scare him. At this point, we have no idea where Abumrad is. This actuality noise builds mystery and engages the listener’s curiosity. Abumrad’s voice begins to narrate over this recording, overlapping with the sounds of him and Pat in the car. Krulwich jumps in, asking, “well, where are you?” Abumrad explains he was in the Mississippi Delta. By listening to this exchange, we can see how dialogue works to tell a story in a more engaging way than if Abumrad just reported where he was and what he was doing. We also see how Krulwich becomes an audience surrogate, acting as if he too is in the dark and does not know Abumrad’s whereabouts, which is doubtful.

Radiolab co-hosts Krulwich and Abumrad.

This segment also points to the show’s overlapping sound tracks, a technique used to help listeners inhabit Johnson’s story. Abumrad continues to tell Krulwich about his trip to Mississippi. The actuality noise fades out as he segues into discussing Johnson, the myths that surround him, and then blues music. Music, interviews, and archived sounds are woven through Abumrad and Krulwich’s discussion as Abumrad takes us through the history of this myth about Johnson and the devil. In “Crossroads,” their conversation moved listeners from one piece of sonic evidence to another as Abumrad essentially builds an almost academic study of Johnson. We hear interviews with historians and music critics; we hear details read from historical records and artifacts; we hear Johnson’s music. These components are pieced together to convey both an exploration and an argument about Johnson.

At the end, the very work of historiography and compiling past narratives is troubled and complicated. In an interview, a historian recants something he wrote about Johnson. As he studied the famous blues artist through oral histories and official records, he came to find out that there were many guitar players in the South at that time named Robert Johnson. We end the program on this note of uncertainty, but Abumrad tells us that we still have recordings of Johnson and perhaps that’s enough. Johnson’s music plays underneath Abumrad’s words. Then Krulwich directs us to further reading on the topic. Here is where we can see Radiolab‘s goal–not to provide listeners with a clear finite answer to a question about the history of Johnson, but rather to arouse our curiosity on the subject and perhaps encourage us to question dominant narratives of the past.

Thanks for your post, Eleanor. For a final twist of irony, there is a controversy among Johnson fans and scholars regarding the recordings themselves. Some audiophiles claim that some or all of Johnson’s famous San Antonio hotel room recording sessions were recorded 10-20% faster than real time (see, for example, the OfficialArmonist youtube channel). Our perceived notions about the veracity of sound recordings as historical documents might also be constructs.

Thanks Jennifer! You bring up a good point, and considering the inherent mediation of sound recordings, I wonder if we can ever really consider them authentic representations of what an artist has performing. They are absolutely constructs, but also material traces of the past nonetheless, and though I think we cannot argue any ultimate truth about the past, we can explore where power intersects with the past. The fact that so little official history of Johnson remains is actually very telling about the social power and significance of an African American musician in the early 20th century, don’t you think?