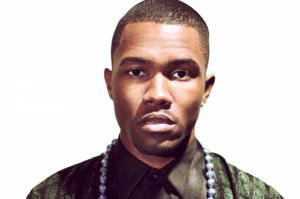

Different for Boys: Frank Ocean and the “Problem” of Male Bisexuality

One of the things that has been driving me bonkers over the past several weeks is the assertion that Frank Ocean came out as gay. Because I have been knee-deep in reading for my impending comprehensive exams, I simply took the assertion that Frank Ocean declared that he is a gay man on Tumblr at face value. BET.com declared rapper “50 Cent Supports Frank Ocean, Gay Marriage,” while Newsday asserted that “Frank Ocean Reveals He’s Gay,” E! Online said “Frank Ocean Not Alone, Five Other Singers Who’ve Come Out as Gay,” and finally, the New York Times asserted that “Hip-Hop World Gives Gay Singer Support.”

One of the things that has been driving me bonkers over the past several weeks is the assertion that Frank Ocean came out as gay. Because I have been knee-deep in reading for my impending comprehensive exams, I simply took the assertion that Frank Ocean declared that he is a gay man on Tumblr at face value. BET.com declared rapper “50 Cent Supports Frank Ocean, Gay Marriage,” while Newsday asserted that “Frank Ocean Reveals He’s Gay,” E! Online said “Frank Ocean Not Alone, Five Other Singers Who’ve Come Out as Gay,” and finally, the New York Times asserted that “Hip-Hop World Gives Gay Singer Support.”

But as I have re-engaged with the story of Ocean’s alleged coming out, it occurs to me that he did not really come out as gay on his Tumblr page. Certainly, Ocean asserting that his first love was a man does not conform to hegemonic notions of masculinity, particularly black masculinity, but by his admission that he had once loved a man, he is thus culturally ascribed the moniker “gay,” even though he has not used that word (to my knowledge) to describe himself. Perhaps the prevailing logic here is, as Anthony J. Lemelle, Jr., asserts in his book Black Masculinity and Sexual Politics, “…Many hold the view that any homosexual act at any time in life means the person is homosexual, a status from which they could never fully recover” (136). In some sense, this is a sexualized turn on the one-drop rule.

Ocean’s failure to use the word “gay” can be understood within the notion that some black gay men embrace calling themselves “same gender loving” rather than gay to escape the racism they perceive within white gay communities. And it cannot go without saying that Ocean has not (to my knowledge) “defended” himself against the charge that he is gay. But, by not using the word “gay,” he could also be trying to have a nuanced conversation about sexuality as fluid, rather than fixed.

What becomes problematic is that hegemonic understandings of masculinity disallow men to select “both” when asked one’s sexuality particularly within mass mediated notions of black masculinity wherein the discourse of HIV/AIDS is inextricably linked to black men having sex with other men on the “down low.” In the popular imagination, the “down low” is socially constructed as black men sneaking around and having sex with men behind their girlfriend’s and wife’s backs. The “down low,” and bisexuality by extension, becomes the way in which we develop a cultural understanding of the seemingly rampant spread of HIV/AIDS among black women. Because our culture still understands HIV/AIDS as a “gay disease,” the “down low brother” becomes Enemy No. 1.

But despite cultural antagonism, Ocean attempts to be sexually both. On his CD Channel ORANGE, which debuted at No. 2 on the Billboard chart, selling 131,000 copies, he lyrically vacillates between imagined male and female lovers. I allow that this bisexuality could be rooted in the notion that men, particularly those within the masculinist musical forms of rock, hip hop, and rap, must assert aggressive heterosexuality. Thus, Ocean may have been working mostly within the hegemonic confines of these musical forms. On the other hand, we are culturally uncomfortable allowing Ocean to, as he does in his song “Monks,” speak about an:

African girl [who] speaks in English accent likes to fuck boys in bands

likes to watch westerns

& ride me without the hands

while one track later, the lyrics for “Bad Religion” find Ocean lamenting “I could never make him love me.”

Perhaps the connection between Ocean and gayness can be understood because his network television debut on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon found the singer performing “Bad Religion,” an ode to homosexual unrequited love. It is my contention here that we are culturally uncomfortable with male bisexuality. Certainly, homosexuality is “bad” because it deviates from the culturally constructed sexual norm, but bisexuality is more problematic because of the sense that it remains unfixed.

But if his alleged coming out never mentions the word “gay” or “homosexual” and his music expresses desire for both same and opposite sex partners, how do we culturally make the leap there? We can make the leap because men, particularly black men in the popular culture imagination, are always already heterosexual. The only place for a man to go once deviating from heterosexuality is homosexuality. Unlike Katy Perry who can kiss a girl and like it (and tell her imagined opposite sex betrothed about it in order to titillate him), if Ocean kisses a boy (or desires to do so), he cannot fit within the hegemonic notions of heterosexuality–despite his attempts to lyrically straddle the sexuality fence.