“Easter Eggs,” Errata, and Apple Maps

In honor of Geography Awareness Week I thought it apropos to take a closer look at some participatory cultures and popular grievances that have concretized around errors in digital cartography — especially in light of the recent and now infamous mapping debacle, Apple Maps.

In honor of Geography Awareness Week I thought it apropos to take a closer look at some participatory cultures and popular grievances that have concretized around errors in digital cartography — especially in light of the recent and now infamous mapping debacle, Apple Maps.

There have always been intentional and unintentional errors in maps. Communities, colonizers, and copyright holders have intentionally altered geographic representations in the name of pride, protection, artistic interpretation, or in order to represent and justify certain unequal power relations. For example, the British government is known to intentionally incorporate errors into their maps in order to maintain and police copyright. “Easter eggs” are purposefully inserted into government owned maps in order to identify illegal copies. These “Easter eggs” typically take the form of non-existent streets (what some people refer to as “trap streets”). However, this copyright tactic is not exclusive to street maps (or the British government), “Easter eggs” also appear in the form of non-existent parks or even rooms in cases where maps of malls or offices buildings are involved. Trap streets and Easter eggs are often very difficult to find and more difficult to distinguish as a copyright “Easter egg” versus an erratum. Mappers and mapping communities, such as participants on Open Street Map, harness collective intelligence, collaborate, or work individually to find and identify cartographic Easter eggs in commercially available maps. The community also boasts an impressive Catalog of Errors that spans five continents. (Easter eggs are not the only method for copyrighting digital maps. Digital watermarking also occurs on the level of code, often without perceptibly altering the cartographic representation or visualization.)

Another example of creating intentional errors in the name of cartographic control occurred in the United States throughout the 1990s. Until 2000, the Department of Defense scrambled civilian GPS signals in order to deliberately produce errors. This security measure known as “selective availability” was introduced in order to exclusively reserve precise GPS navigation capabilities for military and authorized personnel. The scrambled signals (though potentially circumvented with the right equipment) were an attempt to thwart terrorist or enemy use of GPS and precise positioning. Civilian signals were generally accurate and widely accessible, but imprecise. During this period of “selective availability” civilian users publicly complained that their GPS lead them astray, that the GPS didn’t recognize or guide them to their desired destination, that the system identified their car as driving on an adjacent road, or caused them to have an accident by providing erroneous directions. (Sound familiar?) Jokes and snarky remarks in newspaper articles, letters to the editor, and online forums were common. Newspaper coverage throughout the decade mockingly reiterated the tale of a proverbial couple that rely too heavily on a faulty GPS and end up in a lake (for one example see: “Global Positioning Maps: Lots of Fun and Glitches” New York Times, March 25, 1997). Although selective availability is long gone, this particular image of the couple driving into a lake remains intact. The Office parody of navigating with and blindly trusting an inaccurate GPS signal is an exaggerated yet relatable experience among GPS users. (Interestingly, this 2007 episode of The Office is referenced in several legal journals regarding GPS-related torts.)

In other instances, maps have been deemed unintentionally inaccurate in retrospect as new information is discovered about spatial relations, infrastructures, nation-state borders, and as more precise cartographic tools and methods of visualization are developed. If a particular map is not updated to reflect certain geographic information and/or geo-political shifts then the map is guaranteed to have errors. As map use becomes more reliant on digital technologies our maps are bound to have glitches, bugs, and technical difficulties at some point during beta testing or after release.

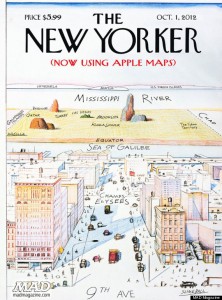

Many of the complaints about Apple Maps are very similar to complaints during the period of “selective availability.” However, the majority of Apple Map contempt focused on the system’s inconsistent mapping interface (which includes a “pretty but dumb” 3D interface) and faulty conflation between data sources, which apparently produces bizarre errors. Discontent with Apple Maps has highlighted everything from unfortunate events caused by inaccuracies in the system, its hasty release despite developer known “bugs,” the accidental disclosure of a Taiwanese air force base, and the frustration associated with what appears to be a sub-par navigation system.

Apple Maps users have noticed melting bridges, disappearing bodies of water, mysterious parks, bomb-like blasts of light obscuring geographic data and have contributed an interminable amount of snide comments, sarcastic parodies, and anti-fan videos regarding the provision of faulty directions or inaccurate information. Facetious Twitter feeds even suggested that certain locations had been so devastated and rearranged by Hurricane Sandy that Apple Maps was now actually accurate.

The Apple Maps complaints were much more widespread and prominent than previous reactions to digital mapping incidents, and the tweets and Tumblrs more shaming and vitriolic. There was also a solid consensus among users and critics that something went terribly awry. Although the map was an easy target for criticism, the general vexation seemed to be fueled by issues with the Apple brand rather than the Apple Map. Many tweets and posts implied that commenters were experiencing a sort of schadenfreude – perhaps pleased to see a company built on sleek, streamlined, hip-ness publicly fail? The comments by Phil Schiller disregarding customer input into the design of Apple products, and Chris Stringer’s description of his role as soothsayer of the future of personal computing during the Apple v. Samsung trial emphasized an image of genius innovators creating cult products around a very exclusive kitchen table. Needless to say, the outward disregard for customer desire didn’t really help Apple’s cause. Additionally, Tim Cook’s public apology to Apple customers was widely considered an odd PR move and resulted in at least one executive being dismissed because he refused to sign the public apology. Many people seemed to find comfort in the defense or coping mechanism that “This wouldn’t have happened under Steve Jobs.”

Furthermore, the Apple Maps quagmire deepened the Apple vs. Google rivalry over service provision. Apple Maps signified not only a bold effort to create its own mobile and web-based map application, but also blatantly replaced Google as a service provider within the iOS 6 upgrade. When iPhone customers “upgraded” to iOS 6 they found that the YouTube and Google Maps applications (services owned by Google) disappeared from their dashboards with the latter being replaced by an image for Apple Maps. Apple Maps was one of the first public attempts by the company to own and promote an Apple branded view of the world, this time in a very literal sense. A view of the world that can be monetized as interest in location-based marketing and services persist, and as the mobile market continues to experience what Larissa Hjorth might refer to as the “app-ification” of location. It would be interesting to compare this moment in Apple’s history to other botched attempts and popular reactions to the release of inadequate Apple products. (One could start with this list of Apple fails compiled by The Guardian’s Technology Blog.)

For at least a decade, digital map users have been rewarded with better services for identifying errors in digital maps, for looking carefully and deeply into the interface in order to find something that didn’t quite mesh between physical space and screen, or that was different and unexpected. In the spirit of Geography Awareness Week it might be valuable to move on from the Apple Maps debacle and investigate the rich and complex participatory and popular cultures that have emerged around access to geocoded information, aggregations and visualizations of user-generated geographic data, mashups, high quality geographic images, and technologies that lower the barriers to DIY mapping and platforms for creative expression on the “geoweb.”

Current design trends in digital mapping aim to create immediacy and immersive spatial experiences. Eric Gordon and Adriana de Souza e Silva have suggested that immersive interfaces, such as Google Street View, and the map as database may actually fuel a user’s fascination with the map itself in addition to (or in lieu of) the spaces and places it represents. This fascination with mapping interfaces and representational spaces like Google Street View has manifest in several communities, websites, forums, games, and Twitter accounts focused on showcasing images of the world, identifying errors, highlighting privacy concerns, and locating unexpected encounters within these cartographic worlds. Fans of geographic information, navigation technologies, and DIY video production have remixed, hacked, and parodied these images in creative, time-consuming, and skillful ways. (And these are only a few examples that take place on one platform.) Apple Maps is an interesting case study that sheds light on the industrial logics and expectations of digital maps as well as the Apple brand, but also ripe for analysis are less prominent or less commercial cases of geographic awareness and participation. Digital traces that represent our desire to play with, produce, and poke fun at location, locatability, mobility, and mapping are ubiquitous – and as the Apple Maps case reiterates, particularly where errors are involved.