Mediating the Past: Licensing History, One Game At a Time

**This post is part of our series, Mediating the Past, which focuses on how history is produced, constructed, distributed, branded and received through various media.

Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series has always been invested in history: its central conceit is a machine, the Animus, that allows hero Desmond Miles to travel through his ancestral past unlocking details of an epic battle between the Assassins and the evil Templars. This overarching story has taken players through a collection of cities such as Florence, Venice, Rome, and Constantinople, each painstakingly recreated based on extensive research on the time periods in question.

Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series has always been invested in history: its central conceit is a machine, the Animus, that allows hero Desmond Miles to travel through his ancestral past unlocking details of an epic battle between the Assassins and the evil Templars. This overarching story has taken players through a collection of cities such as Florence, Venice, Rome, and Constantinople, each painstakingly recreated based on extensive research on the time periods in question.

However, with Assassin’s Creed III the series enters new territory, literally, moving its focus to North America with a game primarily set in Boston and New York during the American Revolution. The result has been an increase in discourse around the series’ approach to history, best captured by Slate’s “The American Revolution: The Game.” Lamenting the lack of realistic portrayals of the colonial era, Erik Sofge writes of Ubisoft Montreal’s bravery in embracing the underwhelming aesthetics of the period with a Colonial Boston that is “boldly, fascinatingly ugly.” Arguing that the general monotony makes the game’s standout moments all the more remarkable, Sofge commends the game, calling it “one of the best, most visceral examinations of the history of the Revolutionary War.”

When considering the Assassin’s Creed series in regards to mediating the past, its relationship to actual history—as in history as it happened—is limited. While heroes like Connor or Ezio might intersect with famous historical figures like George Washington or Pope Alexander VI, or weave their way through a particular historical event, their exploits—science fictional as they are—remain distinct enough that any label other than historical fiction would be undeserved, even if the games’ broader narratives stick largely to basic historical fact (unlike some planned downloadable content).

Indeed, the game’s developers have made a key distinction in the past: in an interview prior to the release of Assassin’s Creed II, creative director Patrice Désilets revealed, “I like to say that histories are licensed. So, yes we can take some liberties, but not too much, otherwise…what’s the point, right?” While we normally consider licensed video games as those based on other media properties—movies, television shows, comic books—the idea of licensing history is similar: the basic details of the licensed property are mediated through the principles of game design and the result is a product undoubtedly based on, but unlikely to be an exact recreation of, the original.

Of course, much as licensed games are often judged based on their authenticity (or lack thereof), Ubisoft Montreal must face questions of historical accuracy; this could lead to Sofge’s effusive praise of the developer’s commitment to representing this period in history, or The Globe and Mail’s objections to the game’s alleged suggestion that “indigenous peoples rallied to the side of the colonists.” Regardless of whether either argument has merit—ignoring that the Globe and Mail argument shows zero evidence the authors have played or even researched the game in question—they reflect the risk and reward in licensing something as meaningful as history, particularly American history: put another way, these same conversations weren’t as visible when the series was licensing European histories less familiar to the world’s largest gaming market.

Although the final judgment on Assassin’s Creed III’s historical accuracy lies in the game itself (which I haven’t played yet), I’m more interested in how the licensing of history is understood within pre-release hype surrounding the release of each game. Ubisoft’s claim to pure historical capital is tenuous, particularly before people have played the game, but they can more readily make a claim to gaming capital as it relates to historical accuracy. The accomplishment is not in the end result—the accuracy of which we can’t even really judge, given we didn’t live in the 18th century—but rather in the painstaking efforts necessary to recreate the minutiae of 18th-century Boston on an immense scale worthy of today’s high-powered consoles. Previews and interviews allow the developers to make this labor visible, detailing the process whereby historical capital is translated through—or, more critically, disciplined by—the logics of game design in order to create the most satisfying experience for the player while nonetheless maintaining that direct line to historical capital.

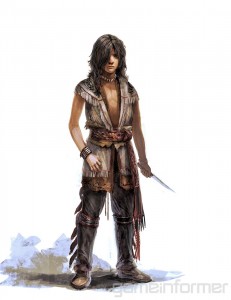

Concept art for the younger version of Connor featured in ACIII.

This notion of discipline is important, here, though: while history brings potential cultural capital, disciplining that history brings cultural consequences, particularly in a game that features a Native American hero (as Connor’s other was of Mohawk descent). Ubisoft’s narrative, however, firmly encloses the discussion of Native American representation within the rigor of the development process rather than the gameplay experience of the final product. Sofge’s article details their cultural sensitivity through the use of a Mohawk liaison and their commitment to authentic Mohawk dialogue, effectively reporting Ubisoft’s due diligence rather than how it manifests in gameplay; a similar process, rather than product, is revealed in Matt Clark’s profile of ACIII writer Corey May. Within game development this level of cultural accommodation is considered remarkable, allowing Ubisoft’s stated commitment to accuracy to potentially circumvent any criticism of how the game’s design complicates its representation of indigenous peoples (as simply the details about May’s diligence seem to impress the professor of Native American studies consulted for Clark’s article, who has not played the game in question).

As with all licensed properties, then, Ubisoft carefully manages the place of history within the Assassin’s Creed series, much as the series itself is closely managed as the developer’s most successful franchise. When Ryan Smith suggested a roaming art installation featuring works inspired by the game’s historical period was more apt to comment on the revolution of the Occupy movement than the generic “Get Out The Vote” connection on offer, Ubisoft responded that “I think that we have tried not to read into this that much, to be honest. At the end of the day, this is just a video game.” The cultural capital of licensing history has value up until the point that cultural capital becomes politicized or problematized, at which point Assassin’s Creed III ceases being about history, and focuses exclusively on the gaming capital to which Ubisoft can more comfortably claim ownership.