Diagnosis: Media Amnesia (and Education)

Following Sarah Murray’s March 11th post on MOOCs, massive open online courses, I would like to continue the conversation, and steer it away from this specific technology into a more general discussion of the uses of new media for education. A number of historical and theoretical studies have looked at new media in a larger framework that examines certain tendencies, discussions, and uses that new media provoke. One of the most frequent experimental uses centers on a new medium’s educational applications. Over the past century a significant number of now “old” new media, including film, radio, and television, have been investigated as cost-effective, efficient, or perhaps superior means of educating students inside and outside of the classroom. Presently, MOOCs are in the middle of what I would deem their “new media moment”—a time in which different individuals, groups, and institutions explore a new medium’s possibilities, with varying degrees of popularity and future success. MOOCs are merely the latest technological-education delivery device that promises to transform the “broken” American education system.

Following Sarah Murray’s March 11th post on MOOCs, massive open online courses, I would like to continue the conversation, and steer it away from this specific technology into a more general discussion of the uses of new media for education. A number of historical and theoretical studies have looked at new media in a larger framework that examines certain tendencies, discussions, and uses that new media provoke. One of the most frequent experimental uses centers on a new medium’s educational applications. Over the past century a significant number of now “old” new media, including film, radio, and television, have been investigated as cost-effective, efficient, or perhaps superior means of educating students inside and outside of the classroom. Presently, MOOCs are in the middle of what I would deem their “new media moment”—a time in which different individuals, groups, and institutions explore a new medium’s possibilities, with varying degrees of popularity and future success. MOOCs are merely the latest technological-education delivery device that promises to transform the “broken” American education system.

This perennial desire to exploit new media for educational purposes exemplifies the profound power attributed to two institutions in the United States: education and technology. To this day education persists, at least symbolically, as the major mechanism of social and cultural uplift, credited with the ability to enable improved intellectual abilities, greater personal fulfillment, better employment, and increased material wealth. Despite a long track record of uneven results, there remains a collective faith in new technology and its unending and always renewing promise to enhance and improve education.

Why do we continuing look to new media for educational quick-fixes? In the September 1956 issue of Educational Screen, Benjamin C. Willis, then General Superintendent of Chicago Schools, attempted to answer this question. He wrote that “it is only fitting that education, which creates technological advance, which makes it possible for our engineers, scientists, and scholars to invent and create new media, should take advantage of some of its products and attempt to use these new advances in the instructional process” (273). Perhaps Willis’s statement explains the oft-repeated rhetoric that touts the educational potential of new media—schools embrace these innovations because they are the intellectual products of the young people who have been taught in these institutions. In this way new media represent the cyclical nature of forward-thinking educational experiments that use new media to mold minds to create new media technologies. They are the realization of the promise of education.

Regardless of the broad interest in a new medium’s earliest days, such as the current stream of articles touting MOOCs, what tends to follow is a steep drop-off in attention when one of two things occurs: either the medium fails to deliver in quantifiable ways, or the next new medium becomes financially viable; the “old” is cast aside to make way for the new. This cycle of obsession over new media and the subsequent disavowal of it creates the cycle of what I term “media amnesia,” whereby the promise of yet-another new technology restarts the dialogue on the perceived potential of a new medium without a thorough investigation into the previous medium’s “failures.”

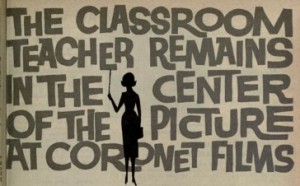

While nearly all new media can be examined as part of this cycle, the most troubling aspect of the rhetoric about the MOOCs is the short-sided nature of the discussions. People such as Thomas Friedman attribute a great deal of promise to MOOCs with particular attention to how they might be used to educate students more effectively or more cheaply in place of traditional classrooms. But the discussion needs to accommodate bigger questions—not on the MOOCs’ own specific attributes, but ones that interrogate within a historically situated context of previous new media. Most contemporary popular press articles fail to contextualize their arguments within the successes and failures of old new media. Adding historical context to the discussion would reveal a pattern of new media, that had previously been regarded as having the potential to reinvent the classroom, but that in the end was only a panacea.

This discussion cannot just be about the supporters and detractors speaking to like-minded audiences. Of course, a number of factors complicate any current investigation. For one, the promise of the “new” seems to be a deeply ingrained tendency in American culture, in terms of our complex relationships with technology, family, work, and the government, with little incentive to contextualize current events with historical evidence. From a capitalistic standpoint, the promotion of new technology for the classroom at once fulfills the emphasis on economic growth through consumer spending and connects it to publicly funded, mandatory education in the United States, a further instance of ways in which individuals and businesses have attempted to monetize privately a seemingly not-for-profit institution. The disconnect between academic research and popular press writing about old new media is also creating two different lines of inquiry that need to be in dialogue with one another. Are all of these issues resolvable or is the disconnect between academics, teachers, for-profit online education companies, and writers just another symptom of the breakdown of in-depth long-form journalism? And what is really at stake here: educating students, saving money, shifting the role of schools and teachers, and/or making private companies more money?