Dolby Atmos: What You Hear

Among practitioners and scholars, there is a common quip that a technological change in film sound amounts to a “quiet revolution” for filmgoers. Last year’s roll-out of Dolby Atmos perhaps only further corroborates this observation. Of the several films mixed and released in the new format — films that include Brave (2012), The Hobbit (2012), and A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) — few mention Atmos in their promotional material. Additionally, filmgoers may be unable to distinguish an Atmos mix from a typical 5.1 or 7.1 soundtrack. Given that films like G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013) were not initially conceived with Atmos in mind, to the untrained ear there may not always be a discernible difference between Dolby’s new format and previous technologies. Nonetheless, Atmos offers a filmgoing experience worth discussing, for if it or a similar system were to become the industry standard, then questions arise as to how its potential aesthetic might shape the way films sound and look. This blog post therefore provides just a few preliminary observations regarding the significance of Dolby Atmos’s technological and stylistic features.

Among practitioners and scholars, there is a common quip that a technological change in film sound amounts to a “quiet revolution” for filmgoers. Last year’s roll-out of Dolby Atmos perhaps only further corroborates this observation. Of the several films mixed and released in the new format — films that include Brave (2012), The Hobbit (2012), and A Good Day to Die Hard (2013) — few mention Atmos in their promotional material. Additionally, filmgoers may be unable to distinguish an Atmos mix from a typical 5.1 or 7.1 soundtrack. Given that films like G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013) were not initially conceived with Atmos in mind, to the untrained ear there may not always be a discernible difference between Dolby’s new format and previous technologies. Nonetheless, Atmos offers a filmgoing experience worth discussing, for if it or a similar system were to become the industry standard, then questions arise as to how its potential aesthetic might shape the way films sound and look. This blog post therefore provides just a few preliminary observations regarding the significance of Dolby Atmos’s technological and stylistic features.

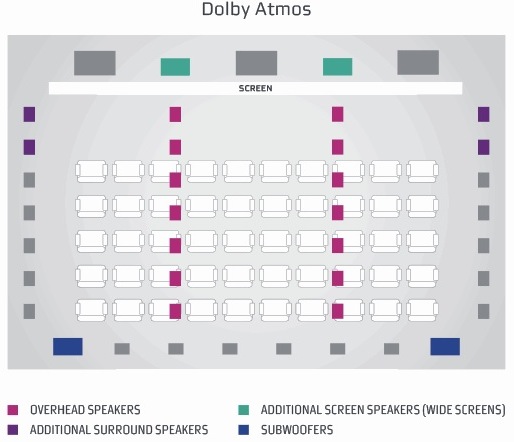

With respect to its mixing capabilities, the Atmos system can send discreet sounds to up to 61 individual speakers and 3 low-frequency subwoofers. This updates Dolby’s recent 7.1 configuration (color-coded below), which consists of three full-range speakers behind the screen, a channel for each side wall, and a left and right channel for the rear wall. Additionally, 7.1 can feed low-frequency effects to an LFE or “.1” channel located behind the screen.

Atmos essentially keeps this 7.1 configuration but adds two more speakers behind the screen, two channels for ceiling speakers, and two additional LFE channels for the theater’s rear corners, creating ostensibly an 11.3 foundation. Generally, this foundation might contain the film’s music, ambient and background sounds, and — in the front speakers — the onscreen dialog and sound effects.

Most importantly, Atmos can send up to 128 sound effect “objects” to any single speaker in the auditorium. Whereas an offscreen bird might emanate from the entire left wall of speakers in 7.1, filmmakers can now mix the soundtrack so the bird emanates first from only the far speaker on the left, then from a front ceiling speaker, then from an adjacent speaker, and so forth if the filmmakers wish to recreate a bird’s circuitous flight through an auditorium. Further, because not every theater wired for Atmos will have the exact same number of speakers, the system can modify where it mixes its sound objects in order for that bird to journey identically through a 37- and 61-channel space.

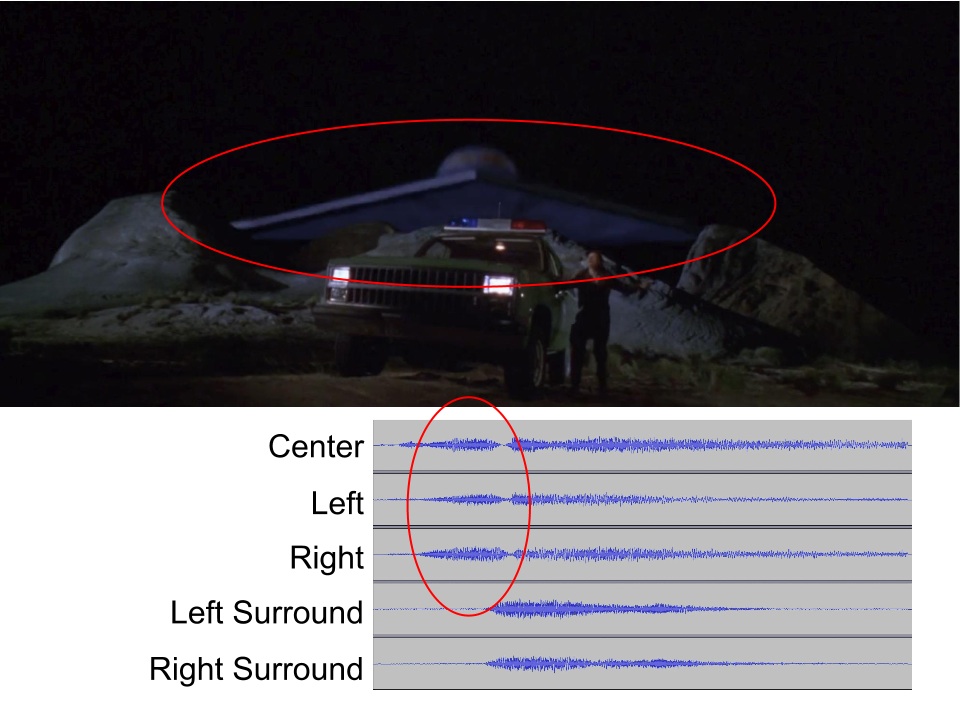

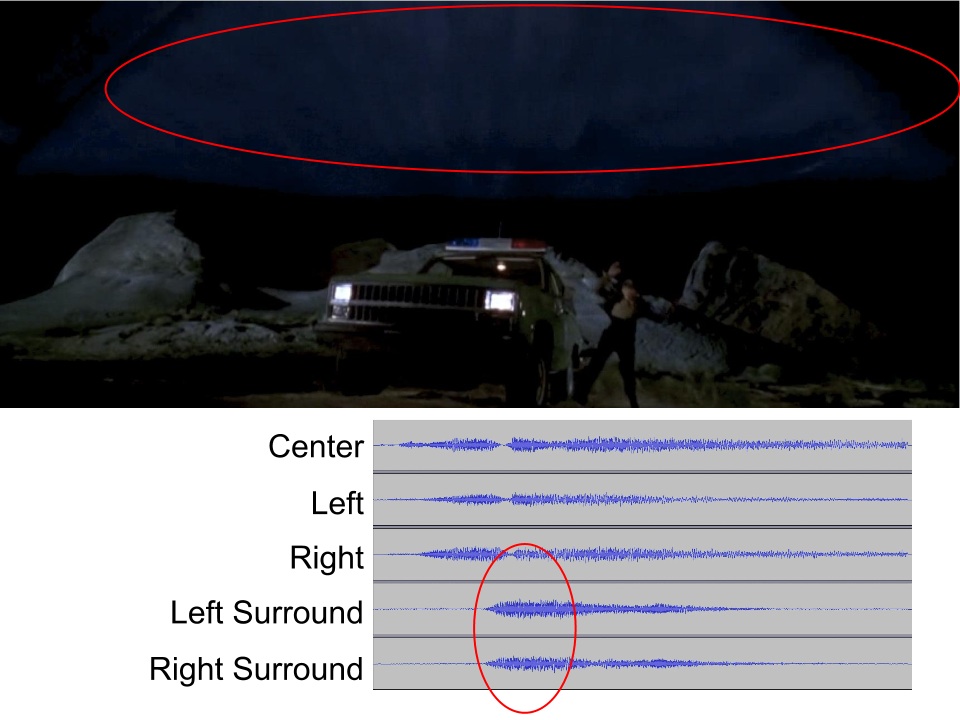

This new means of mixing sound effects is known as a “pan through array,” and—as Dolby argues—the capability is an extensive improvement over the panning limitations of previous formats. Take for instance this early fly-over effect from the 5.1 mix of Broken Arrow (1996). As the airplane travels through the image from the background to the foreground, the sound pans from the front channels into the rear channels (circled in red below), creating the illusion that the plane is also traveling through the theater.

In Atmos these effects still exist, but the added channels on the sides and ceiling allow filmmakers more control over a pan’s speed and intensity. For example, as we crane toward the tornado in Disney’s Oz: The Great and Powerful (2013; pictured below), the storm’s howls slowly engulf one row of speakers at a time in order to create a more foreboding atmosphere and pace.

However, we should not assume that these chill-inducing aesthetics are how practitioners will continue to mix in Atmos once this introductory period is over. To offer some historical context, when Hollywood first introduced digital surround sound to audiences in the early 1990s, films utilizing these new technologies were also sporting aggressive sound designs. For instance, during the final gun battle from Carlito’s Way (1993) we hear screams, gunfire, and other sound effects, yet when we listen to just the two rear surround channels we hear only guns and bullets. The inclusion of only these sounds in the surround speakers would seem to create the illusion that bullets are actually whizzing by the heads of filmgoers.

(Here is an excerpt from the battle with every channel activated…

… and here is the excerpt again with only the rear surround channels activated.)

While Carlito’s Way typifies how 5.1 systems sounded during their first few years, such aggressive and kitschy mixes seemed to become passé by the end of the decade, with these more sensory experiences mainly quarantined for science-fiction or war films, and with most panning effects reserved for interplay between only the front speakers. I suspect a similar stylistic trajectory might also happen with Dolby Atmos.

So in lieu of treating aggressive sound mixing as essential to the Atmos aesthetic, we might conceive of the technology’s long-term appeal in two other ways. First, Atmos replaces each theater’s surrounds with higher-quality speakers that are capable of carrying wider frequency ranges. As opposed to previous soundtracks that were stored on 35mm, the increase in data space afforded to Atmos on DCP hard drives can then allow for more audio information and greater textural detail to emanate from these newer speakers. Second, and perhaps more interestingly, there are the ceiling channels. DreamWorks’s The Croods (2013) noticeably utilizes these new locations through its fabrication of reverberation and echo. During the film’s opening egg chase, the filmmakers mix Alan Silvestri’s A-TEAM-esque score so that it “bounces” off the ceiling like it would in a concert hall or indoor stadium. In addition, both The Croods (pictured below) and Rise of the Guardians (2012) feature fireworks and other elevated actions that take advantage of the ceiling’s speakers.

Ceiling channels and more detailed sonic textures are pleasurable additions, but they may pale in comparison to some of the more chill-inducing moments currently offered by filmmakers. If you are curious about experiencing these aggressive sound mixes firsthand then you may want to plan a trip to your closest Atmos theater before this type of aesthetic once again becomes passé.

Eric– This is a great first stab (or preview?) of how Atmos may work in practice. I appreciate the clips a lot, too, since as someone who’s not as attuned to film sound as I should be, I often have a hard time imagining this stuff without concrete examples.

You may have used the concept of illusionism only for convenience (“creating the illusion that the plane is also traveling through the theater”) but I do wonder if there’s a better way we might explain what’s happening in these instances of panning. There’s definitively some kind of added value to the panning effect in terms of our sensory/emotional engagement with a film. Practitioners (sound designers, directors) typically explain such innovations in terms of illusionism/immersion (e.g. Cameron and Jackson’s justifications for HFR). But recreating this discourse within film studies (as in so many film theories relying on an illusion/awareness binary) seems like a mistake. Most audience members do not actually think a plane is flying overhead. How have scholars of film sound tried to explain this sort of thing without resorting to the concept of “illusion”?

Jonah- Thanks for the comment!

I suspect the distinction between perceptual illusions and cognitive illusions might answer your question. If the the sound is properly mixed, then the plane’s roar through the theater would constitute a perceptual illusion, much in the same way the portrayal of depth on a flat screen would constitute a perceptual illusion. A cognitive illusion, however, would occur if filmgoers were to believe that the plane is really flying over their heads. Depending on the sound — think cell phones or distant thunder –, it is quite possible that filmgoers experience momentary cognitive illusions when listening to the cinema, though obviously I am not suggesting that people need to believe there is a plane in the theater in order for the mix to provide filmgoers with an illusory experience.

So, I would agree that it is problematic to simply parrot a discourse that conflates these two definitions, but I am not doing that in my post. As for finding a better word, I think “illusion” is fine.

I have nothing to append to your response, Eric; I just want to point out that Noel Carroll is one example of a theorist who takes the distinction between perceptual and cognitive illusion fairly seriously, for example, in his POST-THEORY contribution (if I recall correctly).

Eric and Leo– Goes to show how much I’ve learned and forgotten. That’s a useful distinction. So the “illusion” might be that of a single sound object moving through a space (an analogy might be made to the Times Square news ribbon) rather than an actual airplane?

Of course, my bet would be that as a working hypothesis the distinction b/t cognitive and perceptual illusions simplifies messier processes in the brain, and that we’ll come to a better understanding soon enough. But I guess that’s often true.

A good point, and a fair criticism of a lot of film and media scholarship.