Creating is Collecting

In John Bloom’s foundational work on baseball cards and American culture, baby boomers play the starring role. For children of the ’50s and ’60s, baseball cards took on a series of evolving roles over the past half century, moving from childhood toys to quaint remnants of youthful innocence to high risk investment options. Bloom shows that for this generation of American boys, cards served as media through which to express changing understandings of gender-performance, heterosexuality and homosociality.

In John Bloom’s foundational work on baseball cards and American culture, baby boomers play the starring role. For children of the ’50s and ’60s, baseball cards took on a series of evolving roles over the past half century, moving from childhood toys to quaint remnants of youthful innocence to high risk investment options. Bloom shows that for this generation of American boys, cards served as media through which to express changing understandings of gender-performance, heterosexuality and homosociality.

However, by the time baby boomers reached middle-age, economics had taken on an outsized role in shaping the cultural relevance of collecting. The cards of the 1950s and ’60s, based largely on their original use as disposable playthings, became scarce, fetishized objects and grew in value at fantastic rates. Squares of cardboards bought for pennies in 1952 became multi-thousand dollar status symbols by the mid-1980s. As Bloom notes, this increase in value played a crucial part in making the return to youthful, pre-pubescent hobbies socially acceptable for a generation moving towards the peak of its social, cultural and economic power. The impressive price tag of a Mickey Mantle rookie served as economic cover for adults wishing to reengage with a child’s activity.

Unfortunately for those of us born a generation later with aspiration of living the good life off the profits from our collections of ’80s and ’90s cards, things have not worked out the same way. Exactly because everyone thought they would become valuable (and thus no one threw them away), virtually every baseball card produced from the late-70s to mid-90s is worthless. The few that aren’t maintain relatively modest values and, as such obvious exceptions, only serve to emphasize the fact that our painstakingly curated boxes and binders of cards are more useful as kindling for fire than in economic exchange. But, yet, for many Gen Xers and Yers, this has done little to diminish the yearning to return to the pleasures of a past free from work deadlines or romantic desires.

The Internet is now home to thousands of blogs dedicated to collecting but, in a significant turn, relatively few focus on baseball cards in economic terms. Some of the most powerful and culturally relevant sites, in fact, offer entirely new conceptions of ownership or eschew cards as commodities altogether. The first such site, and still one of the most popular, is Ben Henry’s The Baseball Card Blog. Started in 2006 when a Google search for “baseball cards” brought little beyond eBay results, The Baseball Card Blog began with a scanner and closet or two full of cards hardly worth their weight in cardboard. Whereas so many hobby magazines and books are dedicated to objects people dream about owning, The Baseball Card Blog revels in items that most collectors consider burdensome chaff. Nonetheless, the site quickly found an audience both among card enthusiasts and the mainstream press, making appearances in Entertainment Weekly and Bill Simmons’ ESPN column.

Most posts on the site consist of an image of a card that is owned by hundreds of thousands of people and available for pennies, alongside a few paragraphs of ironic, occasionally nostalgic comedy. In employing this approach, The Baseball Card Blog exchanges conventional forms of ownership for one that emphasizes the importance of creativity in cultural practice.

The site not only recasts objects of the past through the reframing capacities of new technologies; it also quite literally recreates the past, taking denigrated bits and pieces of 1980s culture and refashioning them into items even rarer than a 1952 Willie Mays. The Baseball Card Blog produces cards of which zero (actual) copies exist.

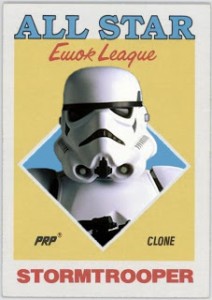

Site creator Ben Henry and artist Travis “PunkRockPaint” Peterson have collaborated on a variety of projects in which they take iconic card templates from the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s and adapt them. Some are simply baseball cards that don’t exist, but would be fun to have if they did. Others embrace what scholar Henry Jenkins describes as the nomadic nature of fans, taking the forms of old baseball cards and infusing them with other elements of childhood play ranging from Super Mario Bros. to The Muppets to Star Wars.

The impulses behind these projects, I argue, are rather similar to those described by Bloom in his discussion of the baseball card boom of the 1980s. Now blessed with economic resources (in time and technology, if not necessarily cash) and burdened with the realities of adult life, there is a strong desire among many children of the 1980s not only to reengage in childhood play, but also to assert control and ownership of it. This is not, of course, an act of true resistance to a corporate-run industry. But it is, nonetheless, an excellent example of how creativity can serve as a satisfying replacement for traditional economic incentives if we only allow it to.