“Vulgar Auteurism:” Out with the New, In with the Old

Of late the label “vulgar auteurism” has become a favorite one for critics seeking to legitimize disreputable helmers like Michael Bay, Tony Scott and John McTiernan. Overtly “formalist,” this supposedly new trend in criticism (need I add that it’s mostly online?) has even yielded its own Andrew Sarris-inspired classification system. In this Pantheon one finds these and a few other popular directors like Steven Spielberg, Kathryn Bigelow and Sylvester Stallone. What gains them admittance, you ask? Quite simply the fact each has a “Complete Auteurist Vision” and “Distinct mise-en-scène.” The project is self-consciously recuperative. What once was new is now old, and so much the better, for the language of old criticism had a purpose and pungency to it.

Of late the label “vulgar auteurism” has become a favorite one for critics seeking to legitimize disreputable helmers like Michael Bay, Tony Scott and John McTiernan. Overtly “formalist,” this supposedly new trend in criticism (need I add that it’s mostly online?) has even yielded its own Andrew Sarris-inspired classification system. In this Pantheon one finds these and a few other popular directors like Steven Spielberg, Kathryn Bigelow and Sylvester Stallone. What gains them admittance, you ask? Quite simply the fact each has a “Complete Auteurist Vision” and “Distinct mise-en-scène.” The project is self-consciously recuperative. What once was new is now old, and so much the better, for the language of old criticism had a purpose and pungency to it.

Whatever the limitations of this new twist on auteurism—and some find that it evinces few if any virtues—it at least raises questions about “the vulgar” in the appreciation of auteurs. Is this a recent story?

To contextualize this trend, Girish Shambu proposes that we distinguish between what he calls classical (i.e., postwar French) and vulgar auteurism. His portrait of French criticism is a familiar one—call it the Sarris Version, elaborated in the famous essay, “Towards a Theory of Film History,” in The American Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1968)—in which Cahiers du cinéma is said to have created a “first wave auteurism” that canonized both artsy directors like Robert Bresson and Jean Renoir and “vulgar” filmmakers like John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock. Classical auteurism praised popular auteurs for marking their movies with distinctive stylistic signatures despite the constraints imposed by industrial production. For Shambu, not only does vulgar auteurism focus solely on “vernacular” genres and styles, but it ultimately lacks the polemical thrust of Cahiers criticism. Unlike François Truffaut who celebrated these auteurs while pouring scorn on the so-called “Tradition of Quality,” contemporary auteurists don’t polemicize against another, odious cinematic form.

But let us not overlook an important fact: French auteurism was always vulgar. While some now view postwar auteurism as elitist, it in fact aimed to popularize good taste in a popular artistic medium and to blur the lines between high and low, the vanguard and the popular. Auteurists espoused a “classical liberal” view of the power of education in the arts, and boldly moved to overturn cultural norms by spreading its sensibility to a new public—to cinephiles—that would, as a result, feel empowered to give voice to its passions. It should come as no surprise that André Bazin was asked to found a “center for cinematographic initiation” at Travail et culture, an institution allied with the French Communist Party that tried to “seize that ancient dream of ‘art for everyone’” (cited in Dudley Andrew, André Bazin (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, 86)).

These aspects of French taste culture encourage us to create more concrete, but also more ambitious, challenges for today’s auteurism.

The strain of “vulgarity” in postwar auteurism reaches as far back as the late 1940s. In 1948, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, André Bazin, Alexandre Astruc, and others founded Objectif 49, a ciné-club that sought to redeem recent films and filmmakers that were “accursed,” that had been misunderstood by middlebrow filmgoers, producers and distributors. The club showed a range of underappreciated movies—ones that represented the best of current cinema, but that had been ignored for being too pretentious or too popular for serious consideration, among other faults—like Sturges’s Christmas in July (1940), Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945) and Welles’s Lady From Shanghai (1947), but also Bresson’s Les dames du bois de Boulogne (1945), Malraux’s Espoir (1945), and Visconti’s Ossessione (1943). As one of the first ciné-clubs devoted to current and future cinema, its screenings and special events didn’t distinguish between “commercial” and “art” films. Both were equally vulnerable for their accursedness, for their variant of vulgarity (popular or pretentious).

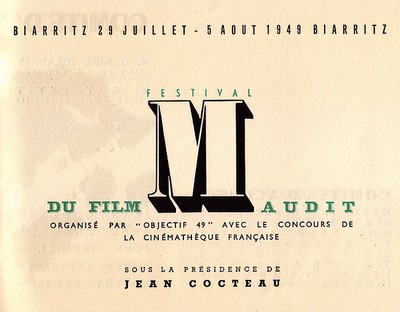

The club’s inaugural festival—the aptly named Festival du film maudit (Festival of Accursed Films, 29 July-5 August 1949)—also raised awareness about the plight of the auteur in the French industry. In a 26 April 1949 press conference broadcast on French radio, Robert Bresson, who hadn’t made a film in four years, lamented the “film maudit” as one “full of remarkable things, though rarely remarked.” The catalogue for the 1949 Festival included an essay by Jean Grémillon on the “Maledictions of Style,” which explored the challenges faced by the auteur whose search for an innovative style was too often met with scorn by distributors who favored less challenging works. Attended by Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Truffaut, the festival might be seen as one among several events that shaped the Cahiers sensibility.

The club’s inaugural festival—the aptly named Festival du film maudit (Festival of Accursed Films, 29 July-5 August 1949)—also raised awareness about the plight of the auteur in the French industry. In a 26 April 1949 press conference broadcast on French radio, Robert Bresson, who hadn’t made a film in four years, lamented the “film maudit” as one “full of remarkable things, though rarely remarked.” The catalogue for the 1949 Festival included an essay by Jean Grémillon on the “Maledictions of Style,” which explored the challenges faced by the auteur whose search for an innovative style was too often met with scorn by distributors who favored less challenging works. Attended by Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette and Truffaut, the festival might be seen as one among several events that shaped the Cahiers sensibility.

The important point is that the ciné-club built a canon; but canon building was not its primary ambition. It aimed to intervene in the careers of the French filmmakers it defended. Objectif 49, as the name suggests, had a mission, an objective: to brazenly challenge an entire industry by cultivating a critical eye for the ways that these and other movies challenged convention. In doing so, it could create an audience—a culture—for a new avant-garde in French cinema. But for these cinephiles the avant-garde was not an experimental non-narrative genre for elites; it was a visionary narrative cinema for a broad public, and thus one that ought to interest producers and distributors. Objectif 49 shaped the period’s vulgate, adding the expression nouvelle avant-garde to the cinephile’s lexicon.

Postwar auteurism was in effect a form of activism—of community- and institution-building that was, quite fittingly, strategically fluid in the auteurs and movies it advocated. It takes more than pantheons and polemics to wield influence over taste culture.

An interesting piece but I can’t resist pointing out the irony of including the implicitly dismissive line “need I add that it’s mostly online?” in a piece that is…ahem… online.

Thank you for the reply. I should immediately clarify that no dismissal of online criticism ought to be inferred from that line! My intention was just the opposite. Isn’t it now redundant to point out that new, fast-moving and, yes, significant conversations about criticism and its functions are emerging in online cinephilic circles? I was trying–and perhaps failing–to take a friend jab those who continue to be surprised by this.

The last line should have read: “I was trying–and perhaps failing–to take a friendly jab at those who continue to be surprised by this.”

Thanks for this necessary history lesson, Colin! I was a little confused too by the promotion of “vulgar auteurism” as something new, since this has been a part of the auteurist impulse from the beginning—that is to say, back farther than Objectif 49 and Cahiers to the championing of e.g. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms by members of the 1920s French avant-garde—including Grémillon. And although they weren’t part of a coherent trend or program, one can detect this impulse in immediately pre- and postwar writing by Otis Ferguson and Manny Farber, as you know.

One thing that bothers me about this “new” auteurism is that, at least as practiced by online critics such as those at Mubi, it frequently reproduces some of the more dubious aspects of the “old” auteurism. Such critics often unquestioningly privilege thematic and stylistic consistency as markers of quality (no capital “Q” btw). This places a premium on strained, willful readings of certain films to pack them into a coherent directorial “worldview” (or a dismissal of films they can’t fit into same). Similarly, such worldviews are often summarized in those grandiose-yet-gaseous terms familiar from the most hyperbolic of Cahiers reviews. At its worst (which is certainly not all of the time!), “vulgar auteurism” steadfastly ignores all but the most convenient information about collaborations, craft practices, and industrial context.

I appreciate the attention paid to McTiernan, Scott, Bay and the resulting observations of their stylistic (and occasionally narrative) contributions. But too often these observations drag along familiar assumptions and fallacies. I’d note that these critics have done little to better-refine the vague notion of “mise-en-scène” they use to praise this or that “vulgar auteur” (I’d except Ignatiy Vishnevetsky and his writing on “workflow”).

On a side note, I think the general failure of the self-described “vulgar auteurists” to confront Zemeckis, one of the most protean of major contemporary directors, suggests the limits of their approach….