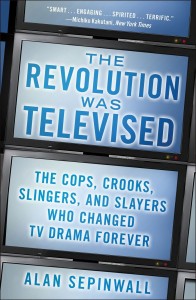

Interview: Alan Sepinwall on TV’s Mold-Breaking—Male—Moment

This is part two of an interview with TV critic Alan Sepinwall about his book, The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever. You can find part one here—part two focuses on the book’s relationship to a period of television history marked by discourses of quality.

This is part two of an interview with TV critic Alan Sepinwall about his book, The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever. You can find part one here—part two focuses on the book’s relationship to a period of television history marked by discourses of quality.

You refer to the book as a history of the period: how do you think your position as a working television critic framed the kind of history you chose to tell? And did this inform how much of your own evaluative criticism made it into the history?

It meant that I was inadvertently embedded for the whole thing. I got that job at The Star-Ledger in part because of my NYPD Blue website. David Milch was one of the first people I interviewed as a 22-year-old newspaper intern. I grew up one town over from (and several decades later than) David Chase, and was writing for Tony Soprano’s hometown paper, for an editor who had been in the same freshman dorm at Rutgers with James Gandolfini. I knew David Simon before The Wire started, knew of Matt Weiner from the Sopranos days. I had a lot of pre-existing relationships that gave me access and/or insight into how the shows got made. And though pre-existing relationships didn’t determine which shows I covered in the book—I’ve spoken with Joss Whedon maybe three times, and I doubt he would remember any of them—it certainly made it easier to do, and put the emphasis on the creator/showrunners involved. But I also think that’s where you have to tell that story, which is what Brett Martin—who notes several times in Difficult Men that he’s not a critic and hasn’t been exhaustively covering these shows for years—chose to do. It’s the auteur theory come to TV, more or less, and these guys (and they are, unfortunately, all guys) were the auteurs.

You acknowledge it’s unfortunate that these “auteurs” are all male, and in choosing your criteria for inclusion you ended up with a book that primarily tells the story of great men who created great TV shows. Was there ever any thought to moving outside those criteria to try to offer something of an alternative to this narrative?

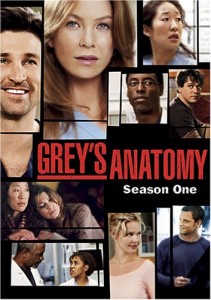

If I could have, I would have. I had already somewhat stretched the narrative to include Buffy and its female heroine. If there was a female-created drama during this period that matched the mold-breaking criteria, I would have jumped all over it. The business, and this corner of it in particular, was especially male-dominated over that period. Shonda Rhimes’ Grey’s Anatomy did debut the same season as Lost, and there are certain ways in which it’s different from what came before, but for the most part it is a really well-executed network hospital drama, with bits of Friends and Sex and the City grafted onto the bones of ER.

One of those shows I perhaps regret omitting from the prologue was My So-Called Life (though it’s mentioned briefly in both The Sopranos and Friday Night Lights chapters), but even there I likely would have had to blurb thirtysomething instead and refer to the other Herskowitz and Zwick shows that followed.

Shows like Grey’s Anatomy speak to an alternate history of the same period, one where shows that weren’t breaking molds were nonetheless a major part of television culture over the past 15 years. By choosing to focus on shows that were quote-unquote “important,” don’t we risk losing a sense of the broader televisual landscape during this time period?

Shows like Grey’s Anatomy speak to an alternate history of the same period, one where shows that weren’t breaking molds were nonetheless a major part of television culture over the past 15 years. By choosing to focus on shows that were quote-unquote “important,” don’t we risk losing a sense of the broader televisual landscape during this time period?

Sure. I’m leaving out enormous swaths of what was happening at this time. Reality is mentioned in passing in the introduction, and in terms of pop cultural impact, Survivor and American Idol had a much bigger footprint than The Wire or Battlestar Galactica. I allude briefly to a few comedies, too. But when I say it’s a history, I don’t mean it as a comprehensive one about TV in this era, or else The West Wing, Sex and the City and a whole bunch of other shows were in there. It’s specifically about the, for lack of a better word, revolution in drama. If you don’t fit that, it doesn’t make you bad; it just makes you the subject of a much broader book.

On the subject of “revolution”: Given the precedents you outline in the prologue and the lengthy period over which these shifts took place, an argument could be made that this is an evolution in which various existing elements of television drama converged. Do we just call it a revolution because it’s sexier, or do you think there’s a more substantive reason why that word has showed up in both your and Martin’s titles?

I think NYPD Blue or Homicide coming from Hill Street Blues, or ER from St. Elsewhere, is an evolution. I think Tony Soprano and Stringer Bell were a revolution. There’s a difference between bending certain elemental rules of narrative and morality and just shattering them. The ’80s and ’90s shows mixed and matched elements that had already existed—Hill Street Blues is basically Citizen Kane, in that no single aspect of it was new, but the combination of it felt new—where the shows in the book were the sort of thing that would have gotten people fired for proposing in earlier eras. NYPD Blue is a great drama, but it also features a lot of compromises for the sake of the network audience; there are no compromises about The Wire.

Your book is one of countless instances where we speak of the “golden age” of television (I believe Martin refers to it as the “third” golden age, for example). Why do you think that idea holds such purchase with those writing about television?

I think people like to categorize things. Comic book fans go on and on about the Golden Age, the Silver Age, and however they choose to dissect the period from around 1973 to today. With TV, there was the clear golden age of Playhouse 90, The Twilight Zone, I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, etc. Then there was Newton Minow’s “vast wasteland” (albeit an era with great stuff like The Defenders and CBS’ ’70s sitcoms) before you get to the ’80s renaissance of Hill Street, Cosby, Cheers, et al. And now we’re either still living in the era created by The Sopranos, or else in the next era made possible by that one. I suppose ideally, we’d have separate names for each of them, but calling it “a new golden age” seems to explain the concept pretty quickly to the casual TV viewer who doesn’t keep track of separate historical epochs.