The Cumulative Narrative of the Cumulative Narrative of Television Studies

Editor’s Note: In April 2013, the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia convened a daylong symposium titled Generation(s) of Television Studies designed in part to celebrate the career of Horace Newcomb and his retirement as Director of the Peabody Awards. Amanda Lotz was among the speakers who reflected on Newcomb’s contribution to television studies. Below is an edited version of her comments to also acknowledge the retirement of this important voice in the field.

The Cumulative Narrative of the Cumulative Narrative in Television Studies (or, Everything I Know About Television Studies, I Learned from “Magnum: The Champagne of TV?”)

The Cumulative Narrative of the Cumulative Narrative in Television Studies (or, Everything I Know About Television Studies, I Learned from “Magnum: The Champagne of TV?”)

It is, in many ways, considerably ironic that I encountered what perhaps remains my favorite piece of television scholarship, “Magnum: The Champagne of TV?,” in Janet Staiger’s “Theory and Literature” class my second semester at UT. It was presented as an example of Neo-Aristotelian analysis, and whether it is that, I’m not sure, but without that class, I may have never found the article—which was published in the more popular television magazine Channels in 1985—that helped me formulate many of my analytic approaches and my basic relationship with my object of study.

The examination of the series provided by the Channels article is concise and wide-ranging; though I’d argue is most significant in proposing the term “cumulative narrative,” as descriptive of the series’ narrative organization. The article’s analysis serves as a reminder of the cyclical nature of many things, including television studies, and is thus a useful lens for connecting the past, present, and future of television studies. The article provides at least seven lessons valuable to today’s practioners of television studies and reminds us of the necessity of being students of both television history and past television scholarship, as despite the seeming urgency of the present, so much we think new has come before.

So in brief, what are the accomplishments of “Magnum: The Champagne of TV?”:

1. It identifies and explains a narrative strategy

As best as I can tell, the Magnum piece offers the first published use of cumulative narrative, which Newcomb explains as: “a ‘new’ television form that stands between the traditional self-contained episodic forms and the open-ended serials” in which “one episode’s events can greatly affect later events, but they’re seldom directly tied together.” He expands this explanation somewhat in a 2004 textbook chapter on “Narrative and Genre” in which he uses the term to describe how a series might use episodic resolution, and yet “rel(y)ies on and frequently mak(e)s specific reference to aspects of character, motivation, and even story that have occurred in previous episodes.” To quote further, “Regular viewers are rewarded with the pleasures of remembering these references, understanding complexities rising from new character developments, and recognizing the potential for future events and characterizations … The ‘cumulative narrative’ might be said to encompass something of a meta-plot that extends over the entire series, in a manner similar to, but distinct from, the fully serialized narrative.”[i]

Though theorized more extensively in the later piece, an important component of what I find profound of the accomplishment of the Magnum article is in its publication in Channels. It is difficult to imagine what the contemporary equivalent of Channels might be. Fully titled Channels of Communications and subtitled The Business of Communications, the journal published from 1981-1990 and was created by Variety critic and author of Television: The Bu$iness Behind the Box, Les Brown who sought for it to “advance a new kind of television criticism, one devoid of the old anti-television cant, that would not make judgments on individual programs but rather would seek to make meaning of television.” It has consistently proven one of the more elusive sources in my own scholarship and tends not to be indexed in databases, but always a rich source when I managed to track it down.

Channels, a magazine that “aimed to interpret for a general readership the developments in the emerging new electronic age and the social issues arising from them,” was particularly important for encouraging a broader conversation about television in an era in which The New York Times and similar outlets were unlikely to fawn extensively over the latest critical darling in the manner common now. Coming back to the accomplishments of this article, published outside the specialized realm of academic literary studies—as any “television studies” remained largely imagined in 1985, “cumulative narrative” provides a term with considerable conceptual purchase, though it largely disappears from use as the focus of “television studies” quickly moves away from more formal narrative analysis.

2. It situates the industrial logic of the cumulative narrative

Though “Encoding and Decoding” was just recently in print in the early 1980s and cultural studies’ theorization of production was still most limited, the article ties this narrative technique with the production economy, particularly the difficulty of telling serial stories in an ephemeral era of television—still pre-VCRs for most, let alone the devices of contemporary viewing—at a time in which viewers could hardly be expected to schedule their lives around a series. Perhaps the nearly 30 years it has taken television storytelling to widely utilize cumulative narrative can be explained by the changed technological and industrial context. Such storytelling is much better suited to the post-network possibilities of DVD, VOD or Netflix-enabled marathon viewing.

3. It engages the writer/producer without fawning or niggling critique

That point needs little elaboration, but related, the article acknowledges the industrial significance of the story creator and provides him with the opportunity to speak of his art by including passages from an interview with co-creator Donald Bellisario. These words, however, are treated as evidence that does not prove or disprove assertions of the text, but exist in conversation with it. The purpose of invoking the storyteller is not to berate or to adulate as a genius worthy of effusive praise.

4. It explores form accessibly, acknowledging the series’ use of particular strategies, such as voice over

“Magnum: The Champagne of TV?” does not use obscure jargon. In fact, “cumulative narrative” may be the most sophisticated terminology in the piece. As such, it is tremendously accessible. It seeks to make its impact not by performing the pedigree of its author’s training, just by using clear and precise language understandable to those who watch, but may not study, television. In addition to naming the concept of cumulative narrative, it discusses other significant narrative features, such as Thomas Magnum’s voice-over narration, noting, “Voice-over narration allows Magnum to carry on a moral dialogue with himself,” simply describing the means by which the series was able to provide a then-uncommon depth of character perspective.

5. It attends, subtly, to the politics of pleasure and the “gush” of the time over Hill Street Blues, St. Elsewhere, and Dallas

As someone who finds The Sopranos and Mad Men to be very good shows, but is also long tired of their overemphasis by the cultural beacons that discuss such things, I really appreciate this aspect of the article. Magnum was perceived by many as a formulaic detective series, coming to air after a decade of exceptional abundance of this form. Its subtle experiment with narrative form was easily overshadowed by Dallas as a prime time serial and Hill Street Blues’ and St. Elsewhere’s experiments with multi-episode arcs. Indeed, these two forms are now so conventional in contemporary television storytelling they rarely warrant mention.

The idea of cumulative narrative, however, has reemerged in Jason Mittell’s developing work on “narrative complexity” and “complex television” in the last decade. It might surprise many to realize the seeds of this strategy originate in Magnum.

6. It poses an alternative to rigid ideological analysis, while still exploring the series’ presentation of Vietnam.

Perhaps another reason for my fondness of this article is its defiance of the conventional presumptions about the significance of the series’ references to the Vietnam War. Where many other pieces of 1980s popular culture invoked Vietnam as an aspect of characterization for more reactionary ends, the analysis does not assume “Vietnam” means the same in this case. Instead, it acknowledges the series’ subtlety in dealing with this back story, both quoting Bellisario who explained, “We decided to treat these guys as if they were World War II vets. They have good memories of the camaraderie, the times they spent together. They have flashbacks, but that doesn’t interfere with their lives. They don’t ‘suffer’ from flashbacks. They have memories. Good ones as well as bad.” While still making the analytic point that, “The issues surrounding Vietnam are not settled in America, nor in this show. Despite Bellisario’s desire to reposition the war, we all know Vietnam was not World War II.”

7. Finally, It anticipates much of the seemingly surprised attention to television’s storytelling abilities, what has in the last decade been identified as—complex TV

I might easily make the same claims made in the article’s concluding paragraphs of those contemporary shows that tantalize and haunt me today. Newcomb’s conclusion also reveals an approach to the study of television that I find both incredibly compelling and too often lacking. To say the article is agenda-less is undoubtedly naïve, but it is certainly the case that it, though strong in point and argument, is not a polemic. It is also not dispassionate, nor does it take the tone of advocacy. Its argument doesn’t have a mission broader than its object of analysis; in illustrating the nature and features of Magnum’s strengths it does not use the single show to make broader claims of television’s greatness or the failures of its other content. It is the account of an observer who is willing—perhaps eager—to learn something new, to be surprised by this well know art and storytelling form. And yet it manages a confidence in its own assertions so as to seem indifferent to persuading the reader of its case:

“Magnum revels in familiarity, but surprises me with new perspectives. It never forgets that its premise is popular entertainment, but neither does it condescend by assuming its audience will not notice and be delighted by small shifts in perspective. This suggests moral complexity, and that is what I most appreciate. Even those things that offend me in Magnum, may, in time, be questioned by the program. They may even change. Having seen this series, I see detective shows differently. I see television differently. And because the show examines, in a television way, the world I have personally experienced, I see the world differently. Magnum is a show that does not forget. And it refuses me the luxury of forgetting the past that brought me here.”

Though I have cited the Magnum article over the years in work attending to various narrative strategies, it was only rereading the piece in its entirety in recent months that I was able to see many of the strategies, approaches, and assumptions that have become natural and un-interrogated in my approach to the study of television.

The perfect conclusion to this talk would be an announcement that the development of a Magnum: PI reboot movie is in the works, as this would underscore the cyclical consistency of the industry as well, which is not so difficult to imagine in this age of Miami Vice (2006) and A-Team (2010) adaptation/remakes. As was the case in 1985, television studies continues to try to bridge critical analysis, popular discussion, and industrial relevance. In what has recently been identified as an “aesthetic turn,” some have returned to the more formal approaches to television texts that were characteristic of early television scholarship that took its methods and theory from literature and film and applied it to television. And some quarters of television studies continue to worry that conversations about “quality” television or the overemphasis of a few series characteristic of excellence have obscured lessons available from those lacking the status of critical darlings.

I close by acknowledging the extraordinary cumulative narrative of a career that began with the first serious consideration of television as a popular art, and closes with a 12-year tenure leading the Peabody Awards, which is devoted to a task no less than “awarding excellence” in broadcast media. The cumulative narrative, television studies, and perhaps Magnum PI, have come full circle. We’ll undoubtedly arrive back to similar conclusions and insights a few decades hence after completing another cycle, but we’ll have to endeavor on this one without the calm, reasoned guidance of the voice who made the avocations of many, including my own, possible—in countless ways—and who has been a generous mentor, provided an exemplar of decency, inspired an area of study, and who can always be counted on to tell a great story.

[i] Horace Newcomb, “Narrative and Genre”, in The SAGE Handbook of Media Studies, edited by John Downing (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2004): 413-22, 422.

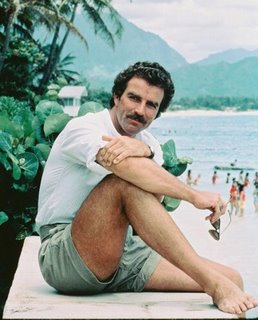

Thanks for a thoughtful and fond rumination on a fine scholar and gentleman. Where did you all find that great old photo of Horace? I don’t think I’ve ever seen him in shorts.