Breaking Bad Breakdown: Exploding Emotion

I’m still a wreck. It’s Monday afternoon, after a late night of obsessing, rewatching, sketchy writing, and furtive sleep. There are few episodes of television that affected me this much—Six Feet Under’s “That’s My Dog” and ER’s “Love’s Labor Lost” are on the short list, but they were both mostly self-contained hours of agony, not the hard-earned payoff of longterm emotional torment on display in “Ozymandias.”

One of the greatest, and truly unique, strengths of serial storytelling is the use of time to build anticipation. This week’s episode harvests so many narrative seeds that were planted years ago, but the emotional fruit that they yield went far beyond my expectations. Thus I spent the entire episode with my hand over my mouth, with my gut in my throat, and with an ever escalating sense of skepticism that things could get any worse. A bit of anecdotal evidence of how much this episode floored me: I buffer everything on my TiVo to fast-forward through ads, but three times in “Ozymandias,” my wife and I sat through the muted commercials just to give us time to recover before the next act began.

I have been waiting for years to see Skyler stand up to Walt (with a knife in hand!), for Flynn (whom I assume outright refuses to be called Walt Jr.) to learn about his father’s crimes, and for Jesse to discover the truth about Jane’s death. I’d played through the dramatic possibilities of these moments in my head, and never came close to the powerful triple punch this episode delivered, with many other unexpected harrowing moments layered on top of them. As I joked on Twitter, this episode felt like encountering a dementor, and I did eat some chocolate to recover.

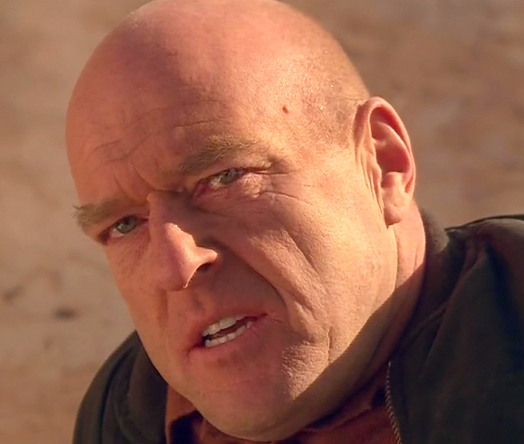

The first harrowing moment was the most expected: the aftermath of the shootout leaving Hank as a dead man, not-walking. Hank knows his fate, Jack knows his fate, only Walt thinks he can reason, rationalize, and lie his way out of it. But as we have witnessed for six years, Walt makes decisions that he believes will offer short-term expediency, but come bundled with unavoidable consequences. When he first allied with Jack’s White Power army, he let loose a force of pure criminal malevolence, showing no concern for pragmatism or compromise. So when Jack does what Jack does, Walt collapses under the realization that he has been dragged across yet another moral line by directly causing the death of a family member. As he lies there while Heisenberg’s buried treasure is unearthed, he abandons the ruse of rationalizing pseudo-morality that he’s just trying to protect his family, and internally says what Jesse proclaimed back in season 3: “I’m the bad guy.”

The first harrowing moment was the most expected: the aftermath of the shootout leaving Hank as a dead man, not-walking. Hank knows his fate, Jack knows his fate, only Walt thinks he can reason, rationalize, and lie his way out of it. But as we have witnessed for six years, Walt makes decisions that he believes will offer short-term expediency, but come bundled with unavoidable consequences. When he first allied with Jack’s White Power army, he let loose a force of pure criminal malevolence, showing no concern for pragmatism or compromise. So when Jack does what Jack does, Walt collapses under the realization that he has been dragged across yet another moral line by directly causing the death of a family member. As he lies there while Heisenberg’s buried treasure is unearthed, he abandons the ruse of rationalizing pseudo-morality that he’s just trying to protect his family, and internally says what Jesse proclaimed back in season 3: “I’m the bad guy.”

This unapologetic craven selfishness manifests itself by topping Jesse’s spit-in-the-face from last episode with an even bigger projectile: “I watched Jane die. I was there and I watched her die. I watched her overdose and choke to death. I could have saved her. But I didn’t.” Unlike nearly every other act of evil we’ve watched Walt commit, this confession has no underlying rationalization. It is said simply out of spite: to show Jesse that Walt had betrayed him long before Jesse became a rat, to restore Walt’s upper hand, to make Jesse hurt. In a season (well, really a series) dedicated to Walt topping each evil action with yet another, this is near the peak of Walt’s fuckery, spiteful and petty with no strategic reward.

Jack has enough of a soft-spot for Todd to let Walt live and get a cut of his own treasure, leaving him to yet another caper in the desert that calls back to previous adventures like in “Four Days Out.” Meanwhile, Marie’s visit to the car wash shows off another pair of Breaking Bad’s strengths. First, it never forgets to ask how other characters might be reacting to the main action—lesser shows might keep the focus on Walt and Jesse, not mining the possibilities of the extended family’s involvement in the drama. Second, the series is expert at exploiting narrative knowledge differentials between characters and viewers. As Marie tells Skyler that Hank has arrested Walt, we squirm in agony knowing what has really happened, at the same time feeling so much empathy for Marie trying to make amends with her sister and restore the family—and anticipating her grief and anger upon learning the truth. This scene is exquisite in delivering the sincere family melodrama that Breaking Bad has always incorporated into its mixture of violent crime drama and pitch black comedy.

Marie’s insistence that Skyler tells Flynn is a brilliant bit of plotting, a development I’d never anticipated, but one that makes complete sense in terms of character motivation. While R.J. Mitte is often dismissed as a weak link in an ensemble of brilliant actors, his performance here is excellent, capturing the teenage anger and outrage toward his mother lying to him, and confusion inherent in having such a story dumped on him in such short order. As we watch them drive home, we know that they soon will face the revelation of Walt’s freedom and Hank’s absence, but are still emotionally invested in their attempt to regroup as a family.

And then the fight. Last week’s desert standoff and shootout felt like the series climax, but the scene in the White’s home might be the most emotionally harrowing moment of a series specializing in harrow. Walt’s lying mojo has dried up, so all he has left is to assert his patriarchal power as the head of his household. Once he realizes that Flynn knows, all he can do is try to gain control by asserting that everything will be alright if only they just follow him. Skyler’s approach to the counter, posing the visual question of “knife or phone?”, is a brilliant moment of filmmaking from director Rian Johnson, about whom not enough praise can be said. The entire fight is just emotional torture, with Skyler finally confronting Walt with the violence he deserves, with Flynn making the leap from disbelief to aggressively defending his mother against the monster of the house, and with Walt’s impulsive trump card by abducting the one family member who doesn’t despise him (yet). The scene reminds me of the wonderful cult-classic film The Stepfather, where the horror of patriarchy becomes literally embodied by Terry O’Quinn—how much would you pay for Rian Johnson to remake that film with Cranston?

And then the fight. Last week’s desert standoff and shootout felt like the series climax, but the scene in the White’s home might be the most emotionally harrowing moment of a series specializing in harrow. Walt’s lying mojo has dried up, so all he has left is to assert his patriarchal power as the head of his household. Once he realizes that Flynn knows, all he can do is try to gain control by asserting that everything will be alright if only they just follow him. Skyler’s approach to the counter, posing the visual question of “knife or phone?”, is a brilliant moment of filmmaking from director Rian Johnson, about whom not enough praise can be said. The entire fight is just emotional torture, with Skyler finally confronting Walt with the violence he deserves, with Flynn making the leap from disbelief to aggressively defending his mother against the monster of the house, and with Walt’s impulsive trump card by abducting the one family member who doesn’t despise him (yet). The scene reminds me of the wonderful cult-classic film The Stepfather, where the horror of patriarchy becomes literally embodied by Terry O’Quinn—how much would you pay for Rian Johnson to remake that film with Cranston?

After regrouping during the ad break, I wondered how the last 10 minutes might approach the exquisite agony of the first 50, but the next sequence matched those heights. It’s hard to steal a scene from Bryan Cranston, but Elanor Anne Wenrich, the very young actress playing Holly, manages to do it. Of course, Cranston (who I’ve heard is renowned for being amazing at working with children) makes every “mama” meaningful in his reaction, as any illusions that he might escape into a fresh start with Holly get submerged into a stew of guilt and longing. As is so often the case on Breaking Bad, the program’s best lines are those that are left unspoken in Walt’s internal monologue.

Which leads to what may be the most complex scene yet featured on the series. Walt phones Skyler to berate her for betraying him, for telling Flynn, for standing up to him with a knife—his rage call is pure Heisenberg id, fuming about the lack of respect he has been given and blaming others for the trouble he has only brought upon himself. He is also calling to exonerate her, to offer the police evidence that he is the monster and she is just the victim of his abusive bullying—it is a parting gift to Skyler that he hopes will allow her to live free while he escapes to die alone in New Hampshire. He is also calling to implicate the viewers, showing us the monster that we have been rooting for (at least up to a point), and particularly portraying the ugliness and bile frequently spouted by the Skyler-hating contingent of Breaking Bad fans—the series is saying, “this is what you sound like,” with as much strong condemnation possible without going so far as to break the illusion of fiction.

What is truly amazing about this scene is how these different layers of meaning can be perceived by different viewers. In my first viewing, I mostly saw the evil Heisenberg letting loose months of resentment and contempt, and the meta-commentary by the series itself in indicting those who have called Skyler a “stupid bitch.” This is what I wanted to see, validating my own interpretations of the series as serial melodrama, rebuking the Skyler hating that I have looked at with disgust, and proving the pure evil in Walt’s heart. It was only via Twitter conversation with my friend Nina Huntemann that I began to seriously consider Walt’s underlying strategy to save Skyler, as I was too consumed by my loathing to consider Walt’s motivations charitably. But just because his call was strategic—and rewatching the final act confirms that interpretation to me, via Cranston’s brilliant performance of subtly letting us in on his internal monologue—doesn’t make what he is saying untrue. Walt’s greatest lies have always been built on truth, and here he does resent Skyler’s judgments, her lack of respect and gratitude, and her decision to tell Flynn; he hates and blames her even as he is trying to apologize and save her. And the series is still condemning the Skyler-hating, even as it represents it via performative, melodramatic excess. It is all these things at once, paying off so many long-planted seeds in a sequence that still makes me anxious after rewatching it four times.

What is truly amazing about this scene is how these different layers of meaning can be perceived by different viewers. In my first viewing, I mostly saw the evil Heisenberg letting loose months of resentment and contempt, and the meta-commentary by the series itself in indicting those who have called Skyler a “stupid bitch.” This is what I wanted to see, validating my own interpretations of the series as serial melodrama, rebuking the Skyler hating that I have looked at with disgust, and proving the pure evil in Walt’s heart. It was only via Twitter conversation with my friend Nina Huntemann that I began to seriously consider Walt’s underlying strategy to save Skyler, as I was too consumed by my loathing to consider Walt’s motivations charitably. But just because his call was strategic—and rewatching the final act confirms that interpretation to me, via Cranston’s brilliant performance of subtly letting us in on his internal monologue—doesn’t make what he is saying untrue. Walt’s greatest lies have always been built on truth, and here he does resent Skyler’s judgments, her lack of respect and gratitude, and her decision to tell Flynn; he hates and blames her even as he is trying to apologize and save her. And the series is still condemning the Skyler-hating, even as it represents it via performative, melodramatic excess. It is all these things at once, paying off so many long-planted seeds in a sequence that still makes me anxious after rewatching it four times.

The most recent seed is planted in the episode’s teaser, with Walt’s phone call to Skyler in a flashback to the series pilot with his first cook. Upon first watch, the teaser seemed to be a nice if underwhelming callback to the series origins, highlighting the parallel use of location between past and present. But upon reconsideration, it is clear how much the teaser sets up the thematic and emotional weight of the final sequence—even the image of Skyler choosing between the knife and phone is prefigured, here selecting the innocuous way to communicate with her husband. Back when Walt had to coach himself on his lies, when Skyler was still obsessed with eBay, there was a casual lightness in their affection—rewatching the opening, Skyler’s tossed off “hey you” moves me as a encapsulation of all their love that will be lost. Walt’s not a good liar yet, but Skyler’s bullshit meter is still stored away, so she’s happy to accept him at face value. When Walt suggests they take some family time together, he means it—the cook is still the means to that end, not the end itself. He’ll go on to do horrible, unspeakable acts, some of which he speaks in this episode, but his partnership with Skyler always functioned as an ideal image in his mind as what he was cooking for, willing to sell his soul to protect.

And those memories, which might as well have been Walt’s own recollections while lying in the aftermath of the To’hajiilee shootout, make the final phone call all the more agonizing. Now Walt can only express his love through lies, horrible abusive lies that speak truth about his anger and hostility toward his wife, his family, and himself. The genius of Breaking Bad and Bryan Cranston’s performance is that he is both the man and monster simultaneously, the family man desperate to find the way out of his predicament and the bitter fallen emperor blaming his partner, his family, and his “stupid bitch” of a wife. Walt both loves and hates his wife, and himself, and expresses all of this at the same time. None of this forgives or exonerates him, and I come away from this episode despising Walt more than ever. But it does explain him, and I feel like I know him more intensely than ever before, despite already being the most deeply rendered fictional character I have ever encountered. And we all get to spend two more hours with him.

Random Notes Pinned to Abandoned Babies:

- Poor, poor Jesse. First Walt sees his hiding place, then he learns that his mentor had effectively killed his beloved, then he is tortured and forced to be Psycho Todd’s meth monkey. I fully expect next episode to heap new agony upon poor Jesse, but in true melodramatic form, his suffering will lead to a triumph. (I hope.)

- Hank’s death was arguably the least dramatic event of the episode, as it truly was inevitable that neither he nor Gomie could get out alive. He got to live his own moment of triumph last week, dying on his own terms rather than forced out of the DEA in scandal. I’ll pour out a bottle of Schraderbrau in memorium.

- Lots of meta-moments abound this week, from the teaser callback to the pilot, to the embedded commentary on Skyler hate. But one Easter Egg moment someone caught and shared on Twitter was while Walt was rolling the barrel through the desert, he passed his long abandoned pants that were discarded in the pilot episode.

- Just a final shootout to Rian Johnson, who directs emotional confrontations as well as anyone working today, and writer Moira Walley-Beckett, one of Breaking Bad’s long-time writer/producers who has scripted so many gems along the way. This was certainly her finest yet, and quite probably the best episode of the series, as Vince Gilligan had teased. It’s all down hill from here.

Paratext of the Week:

We need something fun this week, so here’s a double-shot. First, a knock-off Lego version of the Super Lab, which I would love to own—except that my Lego-obsessed son named Walter does not need such inspiration. Second, Jimmy Fallon did a must-watch parody/homage last week. Enjoy!

[…] confession to Jesse about Jane, Flynn learning about his father’s drug business, that final phone call – the most terrifying to me was the knife fight between Walt, Skylar, and Flynn in their […]