The Hunger Games and the Female Driven Franchise (Part 1)

Female-led film franchises are few and far between, especially in the traditionally masculine genres of science fiction and fantasy. There are, of course, exceptions to this ‘rule’ which I shall discuss in a moment – but, firstly, I would like to point out that I am not implying that so-called ‘boy’s genres’ – science fiction, horror, fantasy, thrillers, etc – and ‘girls’ genres – ‘chick flicks,’ romantic comedies, soap operas, love stories – are anything more than social constructions that replicate the gender politics that continue to pollute the socio-cultural landscape in significant ways. Despite the litany of post-feminist discourses that permeate the cultural sphere with the tenuous claims that equality has now been achieved and women can ‘have it all,’ there remains large-scale inequality in popular culture and, by extension, society at large.

Female-led film franchises are few and far between, especially in the traditionally masculine genres of science fiction and fantasy. There are, of course, exceptions to this ‘rule’ which I shall discuss in a moment – but, firstly, I would like to point out that I am not implying that so-called ‘boy’s genres’ – science fiction, horror, fantasy, thrillers, etc – and ‘girls’ genres – ‘chick flicks,’ romantic comedies, soap operas, love stories – are anything more than social constructions that replicate the gender politics that continue to pollute the socio-cultural landscape in significant ways. Despite the litany of post-feminist discourses that permeate the cultural sphere with the tenuous claims that equality has now been achieved and women can ‘have it all,’ there remains large-scale inequality in popular culture and, by extension, society at large.  Film, television and other cultural forms remain gendered spaces that are bifurcated into male and female pockets.But upon closer inspection, these binary distinctions do not hold weight and collapse altogether when scrutinized. Traditionally masculine spaces, such as the San-Diego Comic-Con, are now attended by many women who engage in Cos-Play and wear their fandom on their sleeves – quite literally in some cases. Moreover, the annual Girl Geek Con gives female fans a space of their own to demonstrate their passion for so-called geek-related culture. A recent article featured in the UK broadsheet newspaper, The Guardian, ran with the headline, ‘The Rise of the Female Geek.’ I hesitate to say that this represents a significant shift, but more that women feel that they can now experience and explore spaces hitherto closed off from them. Historically, perhaps, female fans have always existed, but have been deterred from crossing the ostensible gender boundaries that remain an intrinsic feature of the cultural landscape? Are we witnessing a sea-change here? And does popular culture somehow reflect these shifts?

Film, television and other cultural forms remain gendered spaces that are bifurcated into male and female pockets.But upon closer inspection, these binary distinctions do not hold weight and collapse altogether when scrutinized. Traditionally masculine spaces, such as the San-Diego Comic-Con, are now attended by many women who engage in Cos-Play and wear their fandom on their sleeves – quite literally in some cases. Moreover, the annual Girl Geek Con gives female fans a space of their own to demonstrate their passion for so-called geek-related culture. A recent article featured in the UK broadsheet newspaper, The Guardian, ran with the headline, ‘The Rise of the Female Geek.’ I hesitate to say that this represents a significant shift, but more that women feel that they can now experience and explore spaces hitherto closed off from them. Historically, perhaps, female fans have always existed, but have been deterred from crossing the ostensible gender boundaries that remain an intrinsic feature of the cultural landscape? Are we witnessing a sea-change here? And does popular culture somehow reflect these shifts?

The Hunger Games or ‘How to Overthrow the Government’

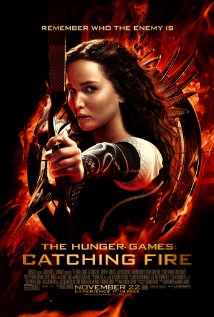

Based on a trilogy of YA (young adult) novels, The Hunger Games features a female protagonist who not only challenges the male-dominated sphere of science fiction and fantasy, but, within the diegesis itself, represents rebellion and revolution on a grand scale. Katniss Everdeen acts as the catalyst that fosters an alliance of the working classes who unite beneath the Mockingjay symbol in order to overthrow the patriarchal order who force participants from each district to fight to the death in an annual-event – the titular Hunger Games – as penance for a previous uprising. From this perspective, The Hunger Games trilogy is political manifesto disguised as a multi-million dollar franchise.

What is interesting in the way in which Katniss Everdeen has been interpreted in the mainstream media as a feminist character. By struggling against the status quo – that is, capitalist and patriarchal – Everdeen’s biology is often put forth as evidence of a feminist agenda. Yet the problem with this viewpoint is that Everdeen does not fight for women’s rights: she fights for everyone. Katniss Everdeen is the Proletariat and, as such, can be read as both Feminist and Marxist which challenges the contemporary ideology. She is a metonym for the 99% – the working classes, whether man, woman or child – and serves as an ideological symbol to unite the exploited, disenfranchised and oppressed people of District 12 (Panem). The message of the story is that ‘there are many more of us than there are of you’ and by coalescing into a faction, the 1% – or bourgeoisie, to use Marxist terminology – which stand at the apex of the economic pyramid, do not stand a chance. As Marx himself put it, the inequalities inherent within the capitalist mode of production will facilitate an uprising when the Proletariat recognizes h/er subjugation and unites to challenge the status quo. ‘What the bourgeoisie therefore produces above all,’ writes Marx, ‘are its own gravediggers.’ In The Hunger Games trilogy, Katniss Everdeen becomes such a gravedigger.

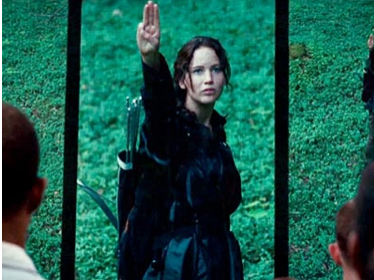

Katniss is one of the most complex characters in popular fiction, at least in recent years, and straddles a fulcrum of femininity and masculinity – she exists in both pockets and thus deconstructs the socially-constructed gender binary. She is, to borrow the words of Alan Sinfield, a ‘faultline’ that destabilises both myth – à la Barthes – and common-sense perceptions – ideologies that have become ‘naturalised’ in discourse.

In an early scene, for example, she is represented as maternal as she ‘mothers’ her sister which dovetails with stereotypical representations of the female figure as ‘nurturer.’ There is, of course, nothing intrinsically wrong about women as maternal – gender is both biological and societal. But to represent women as only mothers is incredibly problematic and succeeds in replicating gender stereotypes that exist – and persist – in contemporary culture and society. Following the scene where she acts as mother to her sister, Katniss takes to the outlying woodlands where we see her line up her bow and arrow to shoot a deer for food. Although she is interrupted by Dale, her male counterpart and friend, we can see Katniss as both hunter and gatherer or, perhaps more pointedly, mother and father. She is an ideological faultine that subverts gender normativity and problematises a succinct separation into binary camps. Moreover, in The Hunger Games, the traditional role of woman as ‘damsel-in-distress’ is subverted and it is her male companion from District 12, Peeta, who requires rescuing.

Of course, themes of resistance in film franchises are not brand-new per se. The Matrix trilogy deals with similar issues and can also be read as a Marxist critique of capitalism, ideology and alienation. The 1970s sci-fi thriller, Rollerball, explores subjugation and resistance to the status quo. Duncan Jones’ Moon is a metaphor for class alienation and oppression. More recently, Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium acts as a thinly-veiled metaphor for the Occupy Wall Street generation and the inequities and inequalities implicit within capitalism and the (unequal) distribution of wealth. All these ideological battles, however, are fought primarily by men. In The Matrix, for example, Neo is ‘The One,’ a patriarch of the resistance. The fact that Katniss Everdeen is both woman and ‘The One’ in The Hunger Games trilogy is a potently charged political statement and one which is very welcome indeed. By operating within a traditionally masculine narrative and generic space while also telling a story about working class resistance to elite rule, the franchise challenges the ‘rules’ in significant ways.

(To Be Continued).

Thank you for this piece!

Before you continue, however, it is maybe worth noting that you’ve uncovered the same problematic relationship between fiction and theory that other critics have stumbled upon in their interpretations of popular genre exercises, particularly the works of science-fiction. The majority of cultural theory has tacitly borrowed metaphors — like ‘capitalism is a dystopia’ and ‘media is a state-controlled religion’ — from the sci-fi genre in order to help illustrate and evaluate difficult concepts concerning class dynamics and other inequities during discussions of ideology. It is then no surprise that works of science fiction then seem to illustrate — if not symbolize — these very concepts that have been batted about in the more politically driven spheres of cultural studies. In fact, many of these concepts are very often on the surface of these texts — The Matrix and Hunger Games being prototypical examples — and are used to help sell the film as more socially important to audiences that might otherwise ignore the franchise for being standard genre fare — a point you bring up with respect to the gendering of science-fiction.

Therefore, instead of uncovering meaning behind this particular franchise, I think what you might have uncovered is a feedback loop between cultural theory and science-fiction, one that seems to be driving your own interpretations of The Hunger Games and its politics, but one that does not appear to be have changed with any consequence over the past several decades, even with this particular instance’s inclusion of a female protagonist in an all-white society.

That said, I enjoyed your post and look forward in reading its continuation!