Say My Name: Unnamed Black Objects in This Year’s “Quality” Films

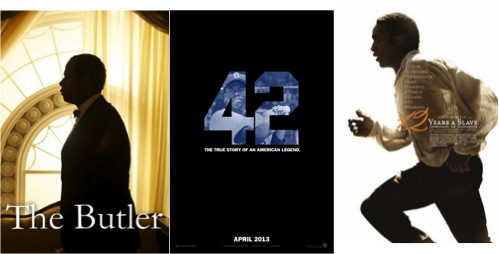

This year has been heralded as a renaissance for films featuring black actors and actresses. Many of these black actors and actresses have performed in “quality” films like 42, The Butler, and 12 Years A Slave. As an arbiter of their “quality” these films have already begun racking up award nominations, and in some cases Critics Association awards. However, there is something these three films have in common besides the ways they center black men’s lives and their inclusion within quality discourses. What is more important are the ways the titles of the films underscore Hollywood’s continuing failures in depicting and portraying black bodies, particularly as it relates to the ways these films are titled, suggesting that black bodies are really just inanimate objects – a number (42), domestic help (The Butler), and chattel (12 Years A Slave).

This year has been heralded as a renaissance for films featuring black actors and actresses. Many of these black actors and actresses have performed in “quality” films like 42, The Butler, and 12 Years A Slave. As an arbiter of their “quality” these films have already begun racking up award nominations, and in some cases Critics Association awards. However, there is something these three films have in common besides the ways they center black men’s lives and their inclusion within quality discourses. What is more important are the ways the titles of the films underscore Hollywood’s continuing failures in depicting and portraying black bodies, particularly as it relates to the ways these films are titled, suggesting that black bodies are really just inanimate objects – a number (42), domestic help (The Butler), and chattel (12 Years A Slave).

By refusing to name Jackie Robinson, Cecil Gaines, or Solomon Northrop, these films do more to serve broader narratives about an alleged post-racial America. Rather, these stories, filled with suffering, noble Negroes, ultimately are less concerned with these black lives (after all, they are nameless as far as the titles are concerned). They fit a cinematic post-racial narrative that suggests that most of America’s racial problems are in the mythic past.

While these narratives follow Black characters, they are not primarily invested in telling the stories of Jackie Robinson, Eugene Allen/Cecil Gaines, or Solomon Northrop. Instead black men function as props in their own tales, which ultimately aim to “teach” liberal white viewers about the “horrors” of slavery and pre-1965 life in America from within the safe confines of their nearest Cineplex; the conclusion of each film provides a neat way to close the door on those histories. Jackie Robinson goes on to integrate baseball and in 1997, his jersey number, 42, was retired across Major League Baseball. Eugene Allen/Cecil Gaines finally gets the White House Head of Staff promotion he deserves and meets President Barack Obama to close the post-racial loop, demonstrating that if black people just “go slow” they will get the rights they want (and implicitly deserve). Lastly, as the film’s narrative ends, Solomon Northrop is reunited with his family, implicitly suggesting that his wrongful enslavement had been righted (although that was not a typical outcome for many free black men and women who were wrongfully re-enslaved). Ultimately, these films are more concerned with providing satisfying narrative closure than showing the things that were as narratively neat in these men’s lives – like Solomon Northrop’s inability to sue the men responsible for his re-enslavement.

Ultimately, 42, 12 Years a Slave, and The Butler are biopics centered on black men’s lives. However, two other biopics released this year help to illuminate the point I am making, Captain Phillips and Philomena. Captain Phillips is centered on Richard Phillips triumph over Somali bodies (whose bodies stand in for blackness) and Philomena focuses on the titular character’s search for the child taken away from her. While there is some cultural understanding of Captain Richard Phillips, there is little cultural knowledge about Philomena Lee. Nevertheless, we understand that we are specifically seeing Captain Richard Phillips’ story. This is Philomena Lee’s story. We understand the centrality of these particular white people’s stories because of our cultural rootedness in the notion that whiteness is multiplicitous while blackness is monolithic.

By excluding the names of Robinson, Allen/Gaines, and Northrop in the film’s titles, these films remove the personal suffering of these men and instead focus on the lessons to be learned. These nameless black bodies then, stand in for a broader black experience that reifies the monolithic cultural understanding of cinematic blackness.

This failure to name these particular black men within the titles of these quality films with black casts (and this argument can be extended to The Help), suggests the utility of the representational labor black bodies are called on to cinematically perform. These films, with their inanimately named titular subjects also stand in for blackness on the world stage. Unlike most films with primarily black casts (and those not deemed “quality” because they are not centered on black suffering) like Baggage Claim or any of the films within the Tyler Perry oeuvre, they are largely segregated into US markets whereas more than a quarter of The Butler’s overall gross was derived from international markets. In this way, the namelessness of the black bodies travels its inanimate self to worldwide markets.

Ultimately then, 42, The Butler, and 12 Years A Slave concomitantly participate in and reify the notion of the nobly suffering negro while also suggesting the relative lack of importance in naming black bodies in film titles. While the titles certainly gesture toward the subject matter of the film, the legacies of the individual stories of Jackie Robinson, Eugene Allen/Cecil Gaines, and Solomon Northrop get lost in translation. Instead, viewers are invited to take the “lessons” of these suffering black bodies and find comfort in the ways black people in American “have overcome,” while allowing the myth of post-racial America to strengthen its roots.