You’ve Come A Long Way, Bonnie?

Who were Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow? Psychopathic killers driven by murderous rage? Victims of social turmoil and an unforgiving criminal justice system that produced the very criminality it sought to contain? Robin Hood like figures challenging the intertwined institutions of capitalism and the state that had so failed them during the Great Depression? Romantic desperados who first yearned for then cursed the celebrity status that made it impossible for them to ever escape identification? Victims of an overbearing and growing police apparatus?[1]

From a period roughly dating from 1932 to their deaths in 1934, newspapers, newsreels, and radio eagerly served up their exploits to a public enthralled by the exploits of Depression era bandits. The mostly small time crimes of the Barrow gang were not sufficient to draw attention, that credit goes to Bonnie Parker. Her romance with Clyde and female criminality secured their enduring presence in our cultural imaginary in radio, novels, films, and most recently a 2013 miniseries, simply titled, Bonnie and Clyde. As a radio historian, I am interested in how our interpretations of gendered criminality might have changed in the almost 80 years between their deaths and now, by comparing the miniseries with the popular radio true crime series, Gang Busters, which weighed in with its own two-part dramatization of the manhunt for the criminal couple a mere two years after their violent deaths.[2]

Gang Busters imagined Bonnie and Clyde through the lens of gender deviance, stripping away both the romance between the pair and any hope of romanticizing them.. Bonnie was represented as decidedly unfeminine, the cold, calculating brains next to a weak, doltish, infantile, decidedly unmasculine Clyde. The real hero of the episodes was retired Texas Ranger, Frank Hamer, whose normative masculinity was constructed as the ideal corrective to the pair’s gender failings. The overt moral message of the show was that the public themselves enabled such crime sprees because their over romanticization of bandit crime prevented them from supporting tougher crime legislation.

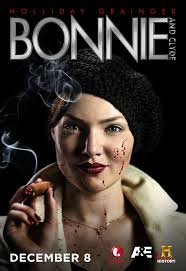

Simulcast across sister cable channels History, Lifetime, and A&E, the lavishly produced Bonnie and Clyde promised, apropos of its cable homes, to offer both historical accuracy and an updated interpretation of the gendered politics of crime.[3] Do Bonnie and Clyde fare better than they did in Gang Busters? Well, Clyde does. So well, in fact, that he is promoted to series narrator, given the power to shape our understanding of the story. If 1936 Clyde is weak and stupid, 2013 Clyde is gifted with a mystical penchant for prognostication and deep abiding love for Bonnie that begins before he even meets her. While the miniseries nods to the poverty that led to Clyde’s life of crime and his horrific experiences at Eastham prison in Texas, as the story progresses, Clyde’s primary motivation seems to be, first, pleasing Bonnie, then making sure that she does not go to jail. His own history does not seem to bear on his future actions. While Clyde’s faithfulness to Bonnie never wavers, his understanding of her lust for fame increases, and he finds himself driven to continued acts of crime in order to satiate her. The romance of the doomed couple is given center stage.

If Clyde is driven by love, Bonnie is motivated by fame. She comes off as a cast member of Real Gun Molls of Dallas—a shallow starlet brandishing her sexuality in search of reality TV style fame and tight control over her criminal brand. Her biggest dream is to leave behind the presumed squalor of her middle class Texas life for the bright lights of Hollywood. All mediated stories play fast and loose with historical “facts,” but which liberties get taken say a great deal about contemporary concerns. A small but significant liberty hinges on a series of photos published that show Bonnie gamely playing with those signs of male criminal virility—cigars and guns. In reality, the photos, themselves largely responsible for the couple’s celebrity bandit status, were published after police recovered the undeveloped roll of film following an unsuccessful raid on the Barrow gang in Missouri. In the miniseries, Bonnie masterminds the pictures, insisting that they all dress well. In the absence of Instagram, she mails them to scrappy, fictional newswoman, P.J. Lane, who bears a striking resemblance to Rosalind Russell’s Hildy Johnson in His Girl Friday, and stands for The Newspaper and its publicity machinery. Celebrity is Bonnie’s game. While Clyde’s fantasy sequences are grisly premonitions of impending violence, Bonnie’s are gauzy images of her as a ballerina soaking up the applause of adoring fans. We see her gamely pouring over newspaper clippings and trying out their celebrity bandit name, opting for Bonnie and Clyde over Clyde and Bonnie.

In its attempt to strip all glamour from Depression era celebrity bandits, Gang Busters flattened the pair into one-dimensional gender deviants, incapable of romance, and lost to any hope of audience sympathy or identification. Bonnie and Clyde centers, rather than shies away from, the romance between the pair. In our contemporary age of the “complex” male anti hero (Walter White, Don Draper), Clyde is more fully imagined as sensitive, knowing, beleaguered by love, and often troubled by the morality of the pair’s actions. Bonnie, however, is imagined through contemporary post feminist anxieties over the meaning of femininity in the era of constant display. Instead of pathological gender deviant, she is now little more than a narcissistic fame monster. The radio series opts for a tale of pathological criminality, while the miniseries opts for an insular story of romance that centers on Bonnie’s dangerous lust for fame and Clyde’s inability to control it. In Gang Busters death is the only option to stop their killing spree. In Bonnie and Clyde, Clyde’s only option is to drive them to their death to arrest Bonnie’s quest for fame. 80 years later, Bonnie doesn’t seem to have come very far at all.

[1] For an excellent discussion of celebrity and bandit culture see Claire Bond Potter’s War on Crime.

[2] For a fuller description of the Gang Busters take on the pair, you can see another piece I wrote on this miniseries here.

[3] The mini series is purposefully set against the 1967 Arthur Penn directed film of the same title.