From Mercury to Mars: After the Martians: The Invasion of “Daytime” in the War of the Worlds Controversy

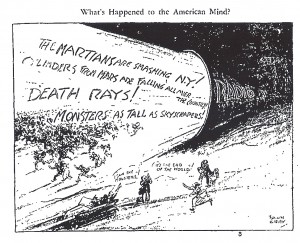

Cartoon reprinted in Howard Koch’s The Panic Broadcast: Portrait of an Event (1970).

In an impassioned letter to the FCC the morning after the famous 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast, Skulda Baner of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, protested the control that the “99%” had over network radio schedules. Urging the FCC to stand strong against the hysterical masses unnerved by the broadcast, Baner argues:

“From morning to night radio is packed with Pacifiers. Give us who are weaned to more solid foods something to fill our bellies, too! Let us have our Mercury group – intact, uncastrated, unsterilized, unchained. Or else… wrap your whole damn’ radio system in cellophane and tie it with pretty pink ribbon and hand it, in tote, to Kindergarteners Incorporated, U.S.A. to play with forever and forever! [sic]”[i]

The vivid imagery in this letter – radio programs as pacifiers, the Mercury Theater players “uncastrated,” a radio system shrink-wrapped, feminized and turned over to the masses – exposes much of the gender (and frankly class) discourses underpinning the American Broadcasting system. What I find so intriguing about the heated public discussion immediately following the War of the Worlds broadcast – in letters to the FCC and to Orson Welles, in newspaper pages, and in industry trade journals – is not just the way the controversy comments about the power of radio or the susceptibility of the audience, but the way in which the gendered logics embedded in the broadcast system rose to the surface in these debates and informed the popular, industrial, and regulatory discussions about the mass “hysteria” of October 30, 1938.

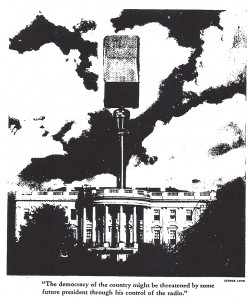

From Herbert Corey’s article “Radio’s Growing Pains,” Nation’s Business (February 1939).

Under the cover of daytime, as Michele Hilmes would phrase it, the radio industry and its critics had long engaged in conversations about commercialism, vulnerable audiences, and broadcasters’ responsibilities to these “fragile publics.” By the mid-1930s, the division of the broadcast schedule – daytime hours dedicated to selling products to impressionable female consumers and evening hours devoted to prestigious, big-budget programs aimed at men and their families at leisure – fueled the commercial expansion of daytime and added new force to industry conversations about the susceptibility of the female masses. As national sponsors poured money into melodramatic serials and claimed hours in the daytime schedule for themselves, broadcasters and critics ruminated about the implications of the commercially driven daytime schedule. How did the fragile daytime audience read melodramatic programming like serials? Should broadcasters rein in advertisers and restore balance and variety to the daytime schedule? Did female audiences need to be protected from the programming that presumably they and sponsors loved? Broadcasters’ relative inaction on these questions reflected, in part, their belief that the existence of a rational audience of male-headed families and high-profile evening programming was an effective counterbalance to the hours of profit-making programs aimed at lower class, uncultured and impressionable female listeners. However, the days, weeks, and months following the WOTW broadcast figuratively thrust popular and industrial discussions about the daytime female audience and its influence over broadcast schedules into “prime time.” The reports of “mass hysteria” engendered by WOTW spawned a rather hysterical chorus of journalists, broadcasters, government officials, and citizens (like Skulda Baner above) amazed at the susceptibility of the prime time listening public, concerned about the mass public’s preparedness for war, and fearful of this audience’s apparent size and potential effect on radio schedules.

In this context, fear of the feminization of radio – or, if you will, the invasion of prime-time radio by daytime listeners – shaped the ensuing discussion about what the government should do or not do in response to the broadcast. To entertain further regulation of the broadcast industry, argued Alvin J. Bogart of Cranford, N.J. in a letter to the editor of The New York Times, was to replicate the “hysteria” of impressionable listeners:

“condemnation of the network for the childish hysteria and panic on the part of many listeners would place the Communications Commission on a par with those emotional and somewhat moronic individuals who, in shame at their own credulity and panic, are now indignant and vindictive.”[ii]

To permit indignant listeners and their unrestrained emotions to control radio, suggested Skulda Baner in a follow-up letter to the FCC, was, among other things, to authorize the “emasculation” of radio.[iii] The trade journal Broadcasting concurred in March 1939, arguing that the threat of government censorship motivated by the WOTW broadcast and the FCC’s subsequent investigations into chain broadcasting a few weeks later was making American radio “impotent.”[iv]

Headline from The New York Times (November 1, 1938).

Given this binary, the logical solution to a system threatened by emotion and the feminine masses was thus a “virile” broadcast industry. As much as the press helped to fan the flames of the WOTW controversy as discussed by Michael Socolow and Jeffrey Pooley in their recent Slate article, the press, joined by broadcasters, some listeners, and even some members of the Communications Commission, forcefully defended the radio industry’s right to remain free of government censorship. A strong and unfettered broadcast industry, many in the press argued, was essential to stem the tide of feminization threatening American radio and to protect the mass audience from itself. The public interest would not be served, argued FCC Commissioner T.A.M. Craven, by a “spineless” radio industry.[v] The only reasonable recourse for a FCC without the legal power to censor broadcasts was an Obama-like beer summit on November 7, 1938, a private chat between FCC Chairman Frank McNinch and the presidents of NBC, CBS, and Mutual that resulted in the networks’ pledge that they would watch their charges – their performers and their impressionable listeners – more closely.

Teasing out the gendered logics of the system and the discourses circulating around the WOTW broadcast, I suggest, gives us a deeper understanding of broadcasters’ relationship to their audiences and to the regulatory possibilities open to the FCC in this context. The fear of the feminization of the prime-time radio audience , I suggest, fueled the social scientific research into susceptible audiences that Josh Sheppard spoke about in his previous post in this series, prompted investigations into programming like radio serials in the 1940s, soap operas in the 1970s and 1980s, and daytime talk shows in the 1990s, and legitimated broadcasters’ role as a “guardian” of not just the airwaves, but of radio audiences more broadly. The discursive debates, prompted by the WOTW broadcast, allow scholars a glimpse, if only for a moment, at the operative gendered logics informing the shape and structure of the radio industry.

This is the twelfth and final post in our From Mercury to Mars: Orson Welles on Radio after 75 Years, which was conducted in partnership with the Sounding Out! blog. Thanks to all our contributors for making this a fantastic series and also our readers for following the posts over the past six months.

This is the twelfth and final post in our From Mercury to Mars: Orson Welles on Radio after 75 Years, which was conducted in partnership with the Sounding Out! blog. Thanks to all our contributors for making this a fantastic series and also our readers for following the posts over the past six months.

Miss any of the previous posts in the series? Click here for links to all of the entries.

[i] Letter to FCC by Skulda Baner, October 31, 1938, Box 24, Richard Wilson – Orson Welles Papers, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan.

[ii] Letter to the Editor from Alvin J. Bogart, October 31, 1938, The New York Times, 22.

[iii] Letter to FCC from Skulda Baner, no date, Box 24, Richard Wilson – Orson Welles Papers, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan.

[iv] “Radio Becoming Impotent From Fear of Federal Censorship, Says Article,” Broadcasting, March 1, 1939, 18.

[v] “FCC Is Perplexed On Steps to Take,” The New York Times, November 1, 1938, 26.

Jennifer,

What a great post! Regardless of what controversy came about, Orson Welles was an incredibly talented man. Just by the sheer fact that 76 years later the famous “War Of The Worlds” radio broadcast is still the subject of blogs, news articles, and commentary on Cable News programs. Also, I’m glad that Government Censorship of radio never materialized, if it had, our radio and TV today would be worlds apart from what we have now. Again, thanks for the very good post, I enjoyed reading it.

Great post! Interesting bit about the private chat between the FCC and the networks and the promise that the networks would increase oversight of programming, which at that time was mostly controlled by advertisers and their agencies. It would be nearly twenty more years before the networks took effective program control from advertisers–and therefore actual responsibility for programming. The irony here is that for the WOTW broadcast, Mercury Theater was a sustaining program–and so in this instance CBS couldn’t blame the sponsor!

[…] [Reblogged from Antenna] […]

I really enjoyed this post. I’m also thinking about how much this earlier debate previews our own contemporary debates over “quality” – there is something in the idea of an “uncastrated” Mercury Theater that hints at the gendered implications of debates over what counts as “quality” television today and the way that such claims of quality are often secured over and against forms associated with female/feminine audiences.

I agree. Thank you for the wonderful and insightful post. If only more people would enjoy the arts.