Communal Politics and the Tragic Love Narrative in Hindi Cinema

Narendra Modi’s very recent ascent to political leadership in India has not dampened ongoing controversy surrounding India’s fractured political landscape–particularly the reality of communal tensions and regional disparity that continues to threaten India’s democratic national fabric. Nothing expresses this conflict better than the contemporary spate of “doomed romance” narratives currently prevailing at the Hindi-language box office, from Ishaqzaade (Rebel Lovers, dir. Habib Faisal, 2012) to last fall’s mega-blockbuster, Goliyon Ki Ras-Leela: Ram-Leela (A Play of Bullets: Ram-Leela, dir. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 2013). Characterized by violent, dystopian settings, corrupt feudal power networks, social anarchy, and the evacuation (or absence altogether) of legitimate state institutions, these films feature vigilante lovers struggling against regional nodes of aggressive political authoritarianism that almost invariably ends with a Romeo and Juliet-style martyrdom.

These stories act as contemporary parables for India’s destabilized economic, political and cultural integrity. While Hindi cinema has always explored the couple-in-crisis, the couple’s re-unification at the conclusion of each film was an allegorical enactment of national solidarity, ensuring the viability of both the state and extended social community.While the tragic impetus in previous tales of “doomed romance” was primarily the impossibility of conjugal fulfillment due to class or other circumstantial barriers, the pathos in the current cycle of films is the seduction of zealous communal prejudices that renders existence, either individual or conjugal, wholly impossible. Even as the couple is granted space for romantic consummation, it is the characters’ allegiance to entrenched kin networks and fidelity to the ideals of self-sacrifice that results in total personal and social annihilation. In Ishaqzaade, a film charting the romance of a Hindu boy and Muslim girl against the backdrop of a pernicious religious feud, the attainment of individual romantic desire is hampered by mutual suspicion and duplicity, while the couple’s relationship is distinctly combative rather than sentimental. This is best exemplified by the film’s ending, when both characters embrace and shoot one another in the side as their warring families close in on them.

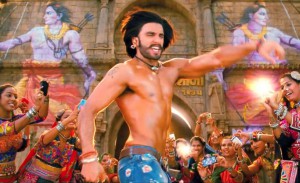

The narrative of Ram-Leela offers a similar trajectory. The protagonists, Ram Rajari and Leela Sanera, first encounter one another in a gun standoff, and while a torrid affair follows, the couple’s misbegotten elopement is never consummated. On their wedding night Ram is deceitfully lured away by friends from his clan, while Leela is forcibly re-captured by her own (the two dynasties have been at odds for nearly 500 years) and they subsequently become divided by feudal entanglements. The couple occupies minimal screen space in the latter half of the film as we witness the formerly desperate lovers stoically perform their communal obligations in a testament to self-sacrifice. Leela nurtures her injured mother, the ruthless matriarch of the Sanera clan, after an assassination attempt for which she mistakenly accuses Ram. Assuming leadership of their respective tribes, both take on political responsibilities that escalate an already hostile conflict to the brink of full-scale genocide. Like Ishaqzaade, the lovers ultimately shoot one another just as a community truce is declared.

By choosing to subsume their identities within a feudal system and honor existing relational commitments, each set of protagonists in both films courts their own destruction – while leaving an emotional lacuna in its wake. We sense that if these characters had fully recognized their compulsion towards individual destiny, at least the catharsis (if not the outcome) would have been different. The viewer is forced to confront the irony of failed individualism that is the genuine tragedy in both texts. These nihilistic narratives, however, have an almost uncanny prescience in the context of India’s riotous political scene. Not only is the idea of nation eviscerated in each text – romantic conjugation is obstructed, communalist sensibilities impede civic harmony, and the premise of citizenship, actualized by the individual, is shunted aside – but the state is completely disempowered in the face of exploitative dynastic politics.

The parallels in each story to real-world developments are telling. The outburst of communal violence in Muzzafarnagar (a district in the state of Uttar Pradesh), during an elections campaign last September, in which the calculated political use of religious propaganda sparked the deaths of both Muslims and Hindus, echoes the 2002 Gujarat riots where over 1,000 people belonging to both communities were killed. Ishaqzaade blatantly evokes the not-so-distant crisis of the 2002 riots by spotlighting the ancestral feudal mentalities and entrenched political interests which continue to inhibit long-term Hindu-Muslim unity – with minimal state intervention. In the opening frames of Ram-Leela, a stunned police officer comments on the fictional town’s outlaw culture, but is quickly eliminated from the scenario, dodging bullets in an effort to escape the town and spare his own life. In addition, at a time when Indian public media is highly critical of the nepotism, social manipulation and clan-like structure of coalition politics, Ram-Leela presents an oblique parody of venal party agendas. For instance, the Rajari clan is associated with BJP-inspired imagery drawn from its Hindu nationalist legacy and affiliation with quasi-militant organizations that glorify conservative Hindu values, including public religious iconography and worship, particularly of Lord Ram. On the other hand, the Saneras are plagued by opportunistic bids for power not unlike the former ruling Congress party today (it is also interesting that the Sanera’s chieftain is an intelligent and fiercely powerful woman, an allusion to the Congress tradition of strong female leaders from Indira to Sonia Gandhi). In the film, both tribes are equally responsible for the violent skirmishes and political out-maneuvering that occurs at the expense of public welfare.

The two films discussed above reflect a weakening Indian state, and its tenuous national identity, as much as they are a disclaimer on the unsustainability of old-world communal politics that continues to haunt India’s civic culture. These competing forces strike at the chord of economic and social livelihood, while increasingly clashing with the values of a rapidly gentrifying, cosmopolitan, and young middle class – the target audience for films like Ishaqzaade and Ram-Leela.