New York Film Festival, 2014, Part One: Small Marvels

This post is part of an ongoing partnership between Antenna: Responses to Media & Culture and the Society for Cinema & Media Studies’ Cinema Journal.

This post is part of an ongoing partnership between Antenna: Responses to Media & Culture and the Society for Cinema & Media Studies’ Cinema Journal.

A breath of fresh air is blowing through the 52nd New York Film Festival. Often the early films are the least interesting offerings of the festival, leaving the press waiting for what is to come. This year a number of the initial screenings have left me wondering whether they can conceivably get any better.

On the second day of the press screenings, we were treated to Jean-Luc Godard’s new film, Goodbye to Language, 70 minutes. It is thrilling, and arguably at least as much of an indication of the future of film as Breathless was in its day. 84 year-old Godard is still kicking like a colt, using 3D now to continue his tradition of cinema without normative plot and characters, with the exception of a dog of indeterminate breed, who might be considered, by some, the film’s star. By means of a sequence of images and aural cues that are both linear and non-linear by turns, Godard explores many motifs in his short film: the oppressiveness of political authorities, books, movies, music, and the absurdity of human endeavor. Interspersed with a parade of people, some of whom become familiar to us, but none of whom we ever know, and certainly none of whom have any sustained goal or dramatic action, are images of the above mentioned dog moving through a forest, or around and in a lake. The people mill around in urban locations often blocked by gates that resemble prison bars, and they are sometimes suddenly and pointlessly seized by men in suits carrying guns, most of whom are rendered helpless by resistance of any kind. Sometimes, the characters talk philosophy in toilets while defecation is taking place, punctuated by appropriate sound effects.

Part of the intelligence of the film is conveyed through the juxtaposition of people and dog, but most of it is in the visual and sound design. Sounds rush at the audience at unexpected moments and Godard’s 3D creates evocative multiple physical planes, much as deep focus did for Jean Renoir in his masterpiece, The Rules of the Game. Except 3D technology permits Godard to articulate these levels with even greater force as he presents us with events taking place simultaneously on numerous layers of foreground, middle ground, and background. As a result, life and technology happen on many levels at the same time, creating a 360 degree impression of the modern world. The specific sequences are impossible to remember after one screening, and, of course, DVD will not be an option for many people as few of us have 3D players at home. Multiple trips to theatres will be necessary.

Part of the intelligence of the film is conveyed through the juxtaposition of people and dog, but most of it is in the visual and sound design. Sounds rush at the audience at unexpected moments and Godard’s 3D creates evocative multiple physical planes, much as deep focus did for Jean Renoir in his masterpiece, The Rules of the Game. Except 3D technology permits Godard to articulate these levels with even greater force as he presents us with events taking place simultaneously on numerous layers of foreground, middle ground, and background. As a result, life and technology happen on many levels at the same time, creating a 360 degree impression of the modern world. The specific sequences are impossible to remember after one screening, and, of course, DVD will not be an option for many people as few of us have 3D players at home. Multiple trips to theatres will be necessary.

But what one takes away from Godard’s darkly comic tone and 3D-heightened sensibility, even after one screening, are questions about what can be known of the outside world by any individual–or dog. (The film is inclined to believe that the dog is most aware.) For example, when at the end the dog sits in repose, a human voice absurdly wonders whether he is depressed or thinking of the Seychelles. To drive home the point that he is unknowable in human terms, the dog appears to leave the film, walking into the woods, but suddenly comes bounding back. We comprehend nothing of his actions, but many may feel comforted by his being, as we are not by the presence of people. Move over Schrödinger’s cat.

Godard’s latest cinematic triumph makes one wonder what Hitchcock could have done with 3D if he had stopped throwing things at the audience through this technology in Dial M for Murder, but rather had played with deep space as Godard does. Imagine the scene in Notorious if he had used 3D instead of an extreme close-up to call attention to the poisoned cup of espresso Alicia (Ingrid Bergman) drinks from. And the mind boggles at the thought of what Welles might have done using 3D instead of deep focus.

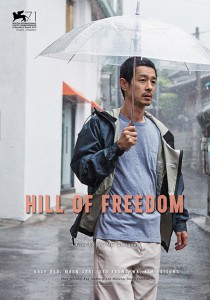

Hong Sang Soo’s Hill of Freedom, a third day offering, also has its charms and its revolutionary aspects. In this 66-minute romantic comedy based on quantum mechanics, Mori, a Japanese man visiting Korea to find his lost love, reads a book called Time, about how we have invented a normative image of space and events in time that doesn’t exist. We know nothing further about the book, but the structure of the plot demonstrates its thesis. The film opens on Mori’s lost love picking up a packet of letters he has mailed in one envelope. She is not well, stumbles on the stairs and drops the undated letters, which she then can only read in random order. As she does, Hong brings to life Mori’s epistolary narration of his adventures in Korea with charming, funny people before our eyes, and perhaps finally his reunion with her. The characters shuttle between a cafe called Hill of Freedom, and the guest house in which Mori is staying. We know where we are, but not when. And without a strongly defined time line we ultimately don’t know if we are choosing to believe that we have seen a happy ending, or whether that desired ending was only a dream. Hong’s film is provocative, human, and delightfully entertaining.

Hong Sang Soo’s Hill of Freedom, a third day offering, also has its charms and its revolutionary aspects. In this 66-minute romantic comedy based on quantum mechanics, Mori, a Japanese man visiting Korea to find his lost love, reads a book called Time, about how we have invented a normative image of space and events in time that doesn’t exist. We know nothing further about the book, but the structure of the plot demonstrates its thesis. The film opens on Mori’s lost love picking up a packet of letters he has mailed in one envelope. She is not well, stumbles on the stairs and drops the undated letters, which she then can only read in random order. As she does, Hong brings to life Mori’s epistolary narration of his adventures in Korea with charming, funny people before our eyes, and perhaps finally his reunion with her. The characters shuttle between a cafe called Hill of Freedom, and the guest house in which Mori is staying. We know where we are, but not when. And without a strongly defined time line we ultimately don’t know if we are choosing to believe that we have seen a happy ending, or whether that desired ending was only a dream. Hong’s film is provocative, human, and delightfully entertaining.

Finally, there is Misunderstood, 103 minutes, the first film on our press schedule, directed by Asia Argento, daughter of famous horror film director Dario Argento, about Aria (Giulia Salerno), the nine year old daughter of a famous (fictional) movie star. In this stunning, funny, and heart wrenching film of her boom and bust life under the uncaring stewardship of two thoroughly narcissistic parents, its principal child actress, probably eleven years old, astonishingly imbues the film with an innocent gravitas as its central character. Beyond the obvious suggestions here of Argento’s biography–Asia/Aria, whose father acts in horror films—Misunderstood rises above family narrative as an indictment of a materialistic age shot through with a devastating form of spontaneity, wallowing in immediate desire, and absolutely lacking maturity. Calling Godard’s dog.

Finally, there is Misunderstood, 103 minutes, the first film on our press schedule, directed by Asia Argento, daughter of famous horror film director Dario Argento, about Aria (Giulia Salerno), the nine year old daughter of a famous (fictional) movie star. In this stunning, funny, and heart wrenching film of her boom and bust life under the uncaring stewardship of two thoroughly narcissistic parents, its principal child actress, probably eleven years old, astonishingly imbues the film with an innocent gravitas as its central character. Beyond the obvious suggestions here of Argento’s biography–Asia/Aria, whose father acts in horror films—Misunderstood rises above family narrative as an indictment of a materialistic age shot through with a devastating form of spontaneity, wallowing in immediate desire, and absolutely lacking maturity. Calling Godard’s dog.

Stay tuned for part two of this series.