Vivisecting The Knick

![]() Much has been made of Steven Soderbergh’s move to television and his direction of Cinemax’s new series The Knick. The show has experienced near-universal acclaim from the critics who have held it up as the best in a new era of director-centered television. But what is it about the show that has warranted these accolades? Four scholars weigh in here:

Much has been made of Steven Soderbergh’s move to television and his direction of Cinemax’s new series The Knick. The show has experienced near-universal acclaim from the critics who have held it up as the best in a new era of director-centered television. But what is it about the show that has warranted these accolades? Four scholars weigh in here:

The Knick’s Clinical Style

Andrew deWaard

Regarding the original script for The Knick, Steven Soderbergh “knew that if [he] said no, the second person who read it would say yes.” In fact, the critical reception of the show seems to find the only flaw to be the script and clunky dialogue, whereas the directing is considered, by Matt Zoller Seitz of New York Magazine, to be “the greatest sustained display of directorial virtuosity in the history of American TV.” We might consider, then, that perhaps the script itself wasn’t necessarily the attraction for Soderbergh, but the opportunity it presented to channel so many of his cinematic preoccupations and skills into one formal package.

Like his early, then-controversial experiment with a multi-platform day-and-date release for Bubble, a practice that has since become common for indie films, Soderbergh is again innovating at the margins of the industry by fronting all ten episodes of a prestige television series, a method that will now be employed by David Fincher and David Lynch as well. True Detective, a show which shares a production company (Anonymous Content) with The Knick, received much acclaim last year for its similar use of only one director, though not to the same degree of singular vision employed by Soderbergh and his many pseudonyms. As Peter Andrews he is the cinematographer and camera operator; as Mary Ann Bernard, the editor, a system he has employed for more than a decade in his filmmaking, as well as his first foray into television back in 2003 for the underrated K-Street.

Like the color-coded storylines in The Underneath and Traffic, as well as the expressive use of yellow in The Informant!, The Knick presents its hospital scenes in a stark monochrome with (literal) splashes of red, its wealthy interiors in bright, claustrophobic decadence, and its underclass exteriors in drab, underlit earth tones; each color palette plays a representative role. The use of natural light with a digital camera is another aspect of Soderbergh’s cinematography that has been honed over the years, from the early miniDV experiment Full Frontal and the HDNet-produced Bubble and The Girlfriend Experience, to the frank, digital depictions of violence in Haywire and pandemic in Contagion.The reasons are technological (Soderbergh was an early, vocal proponent of the now common RED camera), financial (quicker, less costly setups), and performative (less stoppage means more fluid acting), but at The Knick, the lighting is both a literal and figurative concern, from the electrification of the hospital to the dynamics of power and enlightenment that energize the characters.

This visual scheme is also befitting of Soderbergh’s aim to sully the prestige of the period picture through formal means. Like The Good German, which uses only the filming equipment of the era but none of the constraints of the Hays code to present its tale of post-WWII American duplicity, or Che, which focuses on the day-to-day realities of revolution, Soderbergh’s approach to depicting history is to shine a natural light on the process, rather than the spectacle. The opening scene of The Knick features a child poking a dead horse; the rest of the series will graphically demonstrate in clinical detail how the history of technological progress, and early medical experimentation in particular, is not too far removed from that image.

After The Knick, Television Has No Excuse to Not Make Race Meaningfully Visible

Kristen Warner

A look at the professional and personal lives of the staff at New York’s Knickerbocker Hospital during the early part of the twentieth century. Andre Holland and Clive Owen.

Having not noticed the marketing or promotion for the premiere of The Knick, I was unaware of Andre Holland’s presence and was pleasantly surprised to see him on screen in the pilot episode. Holland’s character Dr. Algernon Edwards arrives at the Knickerbocker hospital without much fanfare. The Black Harvard trained surgeon, just returning from a prominent residency in Paris, arrives at The Knick in search of Clive Owen’s Dr. John Thackery who he imagines will heartily welcome him to the hospital. Expecting a clichéd, superficial “race” conversation, I watched the first meeting between he and Thackery with mild interest. However, my mild interest became obsession once I witnessed Thackery realizing he had been fooled into hiring a Black man.

Edwards: I’m beginning to think you weren’t told everything about me. You envisioned something different I take it. Something…lighter.

Thackery: I did. And to be frank Dr. Edwards, I only agreed to this meeting as a courtesy to Ms. Robertson but I am certainly not interested in an integrated hospital staff.

Edwards: My skin color shouldn’t matter.

Thackery: Well if it doesn’t matter why was that information held back from me?

Edwards: You’ll have to ask Ms. Robertson.

Thackery: It’s also nowhere to be found on your credentials.

Edwards: Is your race listed on yours?

Thackery: There’s no need for it to be.

The conversation is a rarity for television because it cleverly allows for race and racial discrimination to exist both at the level of institution and at the individual. Thackery’s reservations about taking Edwards on are not solely bound to his personal feelings but also to the systemic structures that suggested Edwards’ Blackness would operate as an economic hardship for the already struggling hospital. What’s more, that the scene occurs with dark skinned Black coal workers in the background only adds to the layers of privilege Thackery comfortably rests on AND Edwards simultaneously distances himself from.

What’s more, the conversation seeds a larger idea of what Thackery and Edwards’ relationship will be forged upon—economics and efficiency through entrepreneurship. It is only after Thackery discovers Edwards’ underground clinic and learns of the inventions he has created that his Blackness takes a back seat to innovation and he is allowed to exist as more and yet still not enough because his demonstrable title and skill set are only permissible within the confines of the hospital.

Throughout the season we watched Edwards navigate his classed and gendered space between the equally classed and gendered worlds of whiteness and Blackness—because he can never truly belong in either. Cultural specificity as well as questions of racial self-fashioning, repression and respectability are carefully sutured into the text. Where to begin with the richness: Edwards’ Black cohabitants in his hotel whose dignity is tied up in pride and jealousy of what they don’t have, or those he brawls with because he can’t fight the white men, or the Black seamstresses who become surgical nurses (OMG!!) or the Black coal workers who become security for his clinic or his chemistry with my only issue in his storyline: the magically 21st century, post-racialized yet terribly naïve, white love interest Neely? It is rare—as in NEVER—to have such precision and intelligence and depth with regard to Black folks on television, let alone within one season of a series.

This leads to my final point: watching The Knick, I was reminded of the other television historical drama I watch: Mad Men. Years ago I wrote here that while early seasons of Mad Men may have had justifiable reason to strategically exclude Blackness from its text, I believed at some point the series would explicitly include race as part of its frame. As of yet, that still has not happened. Thus that The Knick, a tale of turn of the century New York City can find ways to make Black bodies visible and their experiences meaningful in a time and space they are not normally represented in media without resorting to hindsight smugness and Mad Men, a tale of 1950/60s New York City would not, is quite revealing.

“Pretty Silver Stitches”: the Sounds of Surgery in Steven Soderbergh’s The Knick

Lisa Coulthard

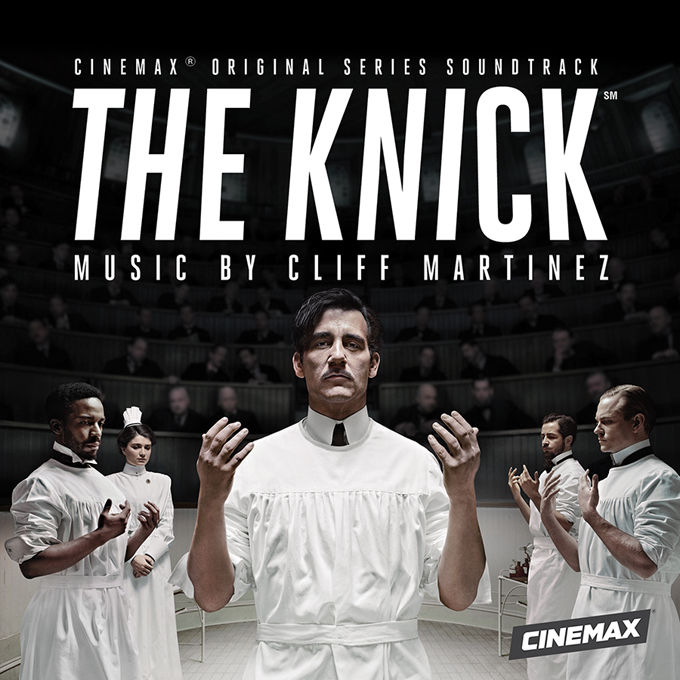

In his influential The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, R. Murray Schafer comments on the phenomenon of disappearing sounds in our acoustic environment — that certain sounds such as leather saddlebags, school hand bells and razors being stropped will someday be extinct and unknown. From the clop of horse hooves and wooden carriage wheels on brick roads to the glass and metal clink of medicine vials and hypodermics, representations of endangered sounds carry with them both a sonic nostalgia and a sometimes uncanny sense of the acoustic dead coming back to life. What is so intriguing about the soundscape of Steven Soderbergh’s circa 1900 New York in The Knick is the way it thoroughly and unambiguously rejects this sonic nostalgia, while at the same time adhering to and celebrating a degree of acoustic historicism. Many have commented favorably on the anachronism of the synthesizer and electronically based music of composer Cliff Martinez (a longtime collaborator of Soderbergh’s), noting that it offsets expectations and avoids clichéd citations of operettas, ragtime, classical or other music one might associate with the era. The complex music for the show instead emphasizes droning minimalism, electronic software synthesizers, and rhythms and tones more resonant of musique concrete than televisual scoring. In particular, the use of the baschet cristal, a mid-century friction ideophone favored by musique concrete composers indicates the musical ties are in not only anachronistic but in direct opposition to the period presented.

But the use of synthesizers and instruments such as the electric guitar or baschet cristal do more than merely distance The Knick from its historically based setting. Stressing sounds more than distinct musical pieces, and blurring effects into music (via heartbeats or similar rhythms), Martinez’s music weaves through the series in an integrated way that, as Jed Mayer suggests, “does not so much accompany scenes as insinuate itself into them.” With no conventional credit sequence or series song, Martinez’s music occupies a pervasive rather distinct presence in The Knick. And yet, with titles such as “Pretty Silver Stitches,” “Son of Placenta Previa,” “Abscess,” and “Aortic Aneurysm junior,” Martinez’s music tracks stress the particular importance of music in the operating scenes. In the same way that Martinez’s use of electronic music and the physical vibratory tonalities of the baschet cristal highlight organic/inorganic binaries, so does the combination of music and sound effects in the surgery scenes. Heavily scored, these surgery scenes are also acoustically graphic – emphasizing the drainage of blood through hand cranked machines or vacuum suction, the spurting flow of fluids, the thud of blood soaked sponges, the metal and glass tings of surgery implements, the sounds effects of the operating room highlight the coming together of organic and inorganic materials in the act of twentieth century surgery. The anachronisms of the music are thus less shocking than one might think – engaged with organic and inorganic materials, blending sonic rhythms with music, and integrating into the action, Martinez’s music works in concert with the historically accuracies of the sound effects to create a split acoustic space, drained of the nostalgia for lost objects discussed by Schafer, but resonant with the coming together of bodies and machines that define the birth of modern surgery, which is after all The Knick’s central drama.

Clive Owen’s Dirtied Star Image in The Knick

R. Colin Tait

In Emily Nussbaum’s original New Yorker pan of The Knick, she stated that her biggest problem with the series is that it relies on cliches that have come to populate the latest iteration of the Premium Cable era of TV. Most offensive of these tropes to Nussbaum is the antiheroic figure of William Thackery — the brilliant, troubled, (ahem…racist) and cocaine-addicted surgeon played with particular fury by movie star Clive Owen. However, Thackery does not merely represent “more of the same” for TV’s era of “Difficult Men,” nor is this type a recent phenomenon. Nussbaum could just as easily be complaining about Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, Macbeth or King Richard the Third as examples of a well-worn type — complex characters whose moral ambiguity is a draw for both audiences and actors alike. Indeed, tragic complexity is nothing new, nor should it be treated as such.

Owen’s portrayal of Thackery is a revelation within his career for several reasons, partly due to the long-form seriality of the series and partly due to his collaboration with Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh has often coaxed career-best performances from his actors. Since he directs, shoots and lights all the scenes himself, the result is a remarkable sense of intimacy with his actors on the set. Second, the director often employs actors to work against their type – as in Matt Damon’s role in The Informant! where the actor gained forty pounds, or, more recently, where Michael Douglas refashioned himself in an Emmy-winning turn as flamboyant superstar pianist Liberace in Behind the Candelabra. Third, Soderbergh employs open framings, long-takes, and shoots little extra coverage, ensuring that the performance in front of the camera is solely the actor’s responsibility and that they bring their best as soon as the camera rolls.

Owen’s performance of Thackery – ranging from his cocaine-inspired megalomania to his pathetic, desperate moments trying to kick the drug – also conforms to a ‘modernist’ streak within Soderbergh’s work, where the actors effectively work so far against their star persona that it becomes “dirtied.” There is almost something of a Brechtian distanciation effect as we watch Owen perform Thackery, and it is impossible to separate the sensation of watching his performance from the sensation of watching the actor wreck their star image.

For Owen, playing Thackery allows the actor to do something that his film roles only partially allowed him to. Indeed, the most memorable Owen parts are the ones where he plays complicated, flawed characters (think Children of Men and Closer here) or where he was a handsome, blank slate (The Hire, Croupier). These characteristics have not always gelled with Hollywood stardom and have ultimately led to Owen only ascending so high as a leading man.

However, the new emphasis on flawed protagonists within cable television allows Owen to sit in his sweet spot. Playing Thackery affords the actor much more leeway to emphasize the traits that made him famous in the first place, ruggedly handsome, taciturn and intelligent instead of the ill-fitting action roles that he has sometimes been shoehorned into as a result of being a leading man in Hollywood.

What all the roles of the cable drama era have in common with Shakespearean drama – ranging from Bryan Cranston’s Walter White in Breaking Bad, to Michael Sheen’s portrayal of William Masters in Masters of Sex, to Owen in The Knick – is they separate the actor from their stardom, distilling each performance down to the specifics of their complexity and allowing the actors and their audiences to revel in the dirt.

Are you aware that the co-creators, and executive producers, of “The Knick” (Jack Amiel & Michael Begler) are University of Wisconsin alumni?