Researching from within kids’ culture

After my first day in the daycare classroom, I thought I had the kids pegged. Just in the span of an hour, one three-year-old told me all about his Batman pants. A girl wearing a Frozen t-shirt happily informed me of the names Princesses printed onto her front. The pièce de résistance occurred when I drew a copy of a Donald Duck figurine—decked out in his The Three Caballeros poncho and sombrero—and asked the class who it was. “Donald Duck!”In that moment I let my confirmation bias win. It seemed as though gendered merchandizing and Disney market saturation had effectively taken over kids’ media culture. However, with weeks of class time with the kids ahead of me, I had to confront some of my assumptions about kids’ culture and the way we communicate at a young age.

The literature on kids’ media culture is dispersed over disciplines that often fundamentally disagree on the goal of studying young people and the media they interact with. While scholars within our field and outside of it have made key interventions into children’s culture, the focus of popular and academic conversations rests on a binary David Buckingham called protectionist and pedagogical discourses. These two discourses articulate the combination of fear and hope centered on the developing bodies and minds of kids—both the perpetual fear of harm caused by sex and violence and the proactive parent-led curation of educational material to foster “proper” growth.

The problems inherent in this model are numerous—due to classed, gendered, raced, and aged biases—, but the issue I will focus on here is the problem of using an adult bias to talk about kids. I believe that this is a major contributor to the troubling construction of childhood innocence. Speaking from our positions of comparably vast experience, we as adult researchers can underestimate children by assuming that their lack of experience is synonymous with lack of understanding. We also at times see the life of a child as foreign or essentially different than our lives, because of our temporal distance from it. By creating our theses and research questions in isolation from children’s perspectives, we continue to ask questions that center on adults and ignore what children may care about or be interested in.

I’m working on a research initiative led by professor and cartoonist Lynda Barry. The idea is to adapt our research questions for young people (and by young I mean two- to four-year olds) and ask them to weigh in on our questions through drawing. As I mentioned before, the class I visit once a week is made up of two- and three-year olds, an age I find especially fascinating for two reasons. First, because this age group is often ignored by psychological research methods that hinge on repeatable tasks. Apparently toddlers do not typically repeat tasks when ordered (this will come as a huge surprise to parents and caregivers, I’m sure). Second is because they are at the beginning of Disney’s supposed princess target audience (girls age two to six). This “princess obsession” is a loaded one since positive and negative associations with hyper-femininity range across class and taste cultures. With both of the above reasons in mind, I am in the process of crafting research questions and methods with the help of my co-researchers. At this point I hope to share a couple brief observations about creating and interacting with toddlers in a space when they are among their peer group and with adults.

1: Dialogue is generative

One of Buckingham’s observations is that we can’t take kids’ words at face value. I think we could often say the same for adults, but it is useful to remember that young children do not always have enough experience to know how we want them to respond to specific questions. Our research objective in the classrooms was to get kids to draw and tell us stories about their drawings. What I discovered was that this age group isn’t fond of or especially equipped to synthesizing visual information into stories. When I ask the innocent question “Will you tell me what you drew?” I’d mostly get frank and negative responses, either “I don’t want to,” “No,” or “I don’t know.” I found it much easier to talk with them while they drew. The “stories” were more like conversations, occurring between myself and a child or two. Dialogue moves beyond verbal communication as well. Thanks to Lynda Barry’s insights, my (adult) colleagues and I discovered that discussion through drawing and playing created more insights from kids than standing at the borders and observing.

2: Repetition helps with creation

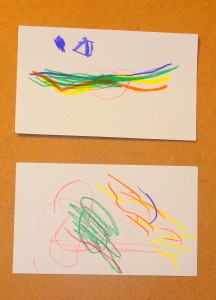

Kids* repeating each other’s drawing ideas. Top: “I’m drawing purple and a rainbow.” Bottom: “I’m starting a rainbow.”

Again, I’ve interacted with toddlers one-on-one, but I was surprised to see how much kids will repeat each other while making things. Often I’d get one kid drawing a “horse” that looked more like squiggle marks and then another kid who didn’t know what to draw would suddenly chime in, “I’m drawing a horse.” This helped me learn how to initiate a drawing session by simply stating what I was drawing and see if anyone else would start drawing the same object. At this stage of practice and motor skills, the kids’ ability to create “realistic” images varied wildly, but by saying they were creating the same thing as a friend, they were able to create something.

So, what do we do with experiences like these? I don’t expect these interactions to write my papers for me or even craft my research questions in a direct way. My hope is that if scholars communicate with children through interactive research methods, we may be able to move beyond thinking about what media culture does to kids, and move toward questions and methodologies that respect kids’ media and cultural engagement as nuanced, active, and social.

*Note: drawings are recreations by the author due to IRB restrictions on circulation of original pieces.

Caroline, this is a very interesting post. In my classroom, I spend a lot of time on drawings, conversations, and written language. When a child approaches me with a picture, I tend to say “tell me about this.” It’s amazing what is generated from that one sentence. Looking forward to hearing more about your research findings.

Thanks so much, Diana. I would love to hear more about the kinds of stories you get with your kids. I can’t remember which age group you have (3-4?), but it would be fun to examine how fast kids learn from storytelling experiences and start to craft their own cohesive tales. I did not get that from these kiddos. They’re still working on synthesizing their insights into the format of narratives adults comprehend as stories.

This is a great post–in studying responses to Disney historically, I often fond that kids’ “actual” voices were something of a structuring absence, with adults either speaking for children (i.e., “protectionist”) or struggling to reconstruct their own sense of having been a child. So, the idea you promote of rethinking how children actually communicate in active and nuanced ways might be key. I wonder too though if this emphasis on “repetition” that children depend upon for communication might also then re-open that space for, as you noted in the beginning, the strength of media saturation to somewhat define their responses (even while that might hardly be limited to children, of course).

Jason–thanks so much. I agree with your point about repetition and struggled to add my own nuance to gendered merchandizing in this post, so I really appreciate the comment. Social repetition seems so important to the kids I work with–it stimulates play and creates bonds. What I want to push back on, maybe in future posts, is the idea that kids are duped by merchandisers, or that they just want what others have. You hit the nail on the head that adults do the same thing. It may be more useful to acknowledge that humans imitate each other, and not blame kids for this seemingly “unconscious” involvement in consumer culture.

I luv it. Great blog posting Pegasus. Your conclusions nailed some of my own experiences. I also enjoy your sense of humor.

Take care, Huck

Thanks, Huck! I look forward to more conversations about your experiences. See you tomorrow.