Tammi Terrell: Marketing Mortality and Reading Album Art

Marvin Gaye has been in the headlines in recent weeks, thanks to a court decision holding musicians Pharrell and Robin Thicke responsible for borrowing Gaye’s intellectual property in their single, “Blurred Lines.” While Gaye’s family has much to gain in safeguarding his legacy and its profit potential, the challenge of outside parties negotiating the marketing of an artist’s body of work doesn’t always begin with the artist’s death. Mercifully rare are instances when serious illness prevents a performer at the height of success from participating in his or her own career. One example can be found in Gaye’s Motown colleague and duet partner Tammi Terrell.

Terrell signed with Motown in 1965, and spent much of 1965-1967 in the studio recording dozens of songs. After a few disappointing singles, Motown head Berry Gordy decided to rework some of these recordings into duets with Marvin Gaye by recording Gaye’s vocals separately and editing the two recordings together. This tactic produced the hit single “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” in April 1967, followed by more singles and the album United in August 1967. In October 1967, Terrell lost consciousness during a live performance and collapsed into Gaye’s arms. She was later diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor, which effectively ended her ability to perform live or record new music until her death in March 1970, at 24 years old.

Terrell’s illness didn’t end her presence on the charts. In an interview with Ebony in late 1969, Terrell mentions that Motown was paying for her treatment, including eight surgeries and extensive rehabilitation (Peters 100). To cover these costs and to insure future royalties for Terrell’s family, Motown would release five more albums and numerous singles drawing on its reserve of Terrell recordings.

The packaging and liner notes of these albums reveals an uneasy tension in how Motown sought to capitalize on Terrell’s success without her direct involvement, alternately confronting and eliding her illness as it suited them. You’re All I Need, the second album of Gaye/Terrell duets, was released in August 1968. The cover features a photo of Terrell and Gaye embracing. When compared with other photos from the same session seen in subsequent reissues and promotional materials, it is apparent that the photo has been rotated, creating the appearance that Terrell is falling into Gaye’s arms. This can be read as a tacit reference to Terrell’s 1967 on-stage collapse, which was widely reported and led to rumors among fans that Terrell had died—rumors she later addressed in the 1969 Ebony interview (Peters 94). The liner notes that accompany You’re All I Need acknowledge Terrell’s health more directly:

The Gaye-Terrell success story is documented by the number of hits they’ve recorded and the loyalty of their fans, who have flocked to witness their superb personal performances at home and abroad. Such performances have been temporarily denied us due to Tammi’s illness. It was strictly Tammi’s love for her art and a quest for the spiritual rejuvenation she always received while working with Marvin that brought Tammi back to Motown to record this album…. Unerringly, Tammi was right. Not only did recording this album contribute to her convalescence, but added a new dimension to the Gaye-Terrell repertoire.

These liner notes conjure a convenient fantasy that exploits Terrell’s illness as a marketing point for the curative power of music; most if not all of the recordings appearing on You’re All I Need were made between 1965 and 1967, during the same sessions that produced United, and before Terrell began treatment.

These sessions would be drawn upon again for January 1969’s Irresistible, the only Terrell solo album released during her life. While presented as a new studio album, it was in fact a compilation of remaining unreleased 1965-67 recordings, several previously released singles and the original unedited solo versions of several Gaye duets. The brief, vague liner notes that accompany Irresistible help to obscure the provenance of the recordings, and make no reference to Terrell’s illness. It’s conceivable that the album was prepared for release years earlier and shelved until the inability to record new material and Terrell’s medical bills hastened its release. 1969 would also see the release of Marvin Gaye and His Girls, a reductively titled compilation that recycled several Terrell/Gaye singles along with songs featuring Mary Wells and Kim Weston. Once again, Terrell’s health goes unacknowledged on the packaging, and the photo of Terrell on the cover is from the same photo session as appeared on United in 1967. Following the relative candor of You’re All I Need, the silence of the presentation on these two albums is hard to ignore.

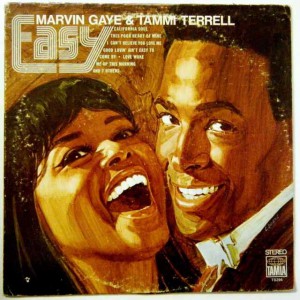

In September 1969, Motown released a third Terrell/Gaye duets album, glibly titled Easy. The album again recycles some previously released songs, but features mostly new recordings. Terrell was well enough to enter the studio during the recording, though accounts differ to this day regarding whether she appears on the finished album, or if the voice is that of Valerie Simpson, who co-wrote many of Gaye and Terrell’s singles and co-produced the album (Montgomery 179; Kot 2; Posner 183).

The unclear details of Easy‘s production are further obscured in its artwork. Of all the albums released by Motown up to that point, Easy was the first to include an image of the performers on the cover that was not a photograph. The cover instead features a tightly framed painting of Terrell and Gaye. The attire and hairstyles suggest that the painting is based on an alternate take from the photo session that produced the cover of You’re All I Need. The back cover of Easy includes no artist photo or liner notes, which is unusual for Motown releases of the period. The sparse layout includes just the album title treatment, the track titles, and recommendations of other Motown releases. The overall presentation seems intended to maximize the nearly exhausted well of material available to Motown, and to distance Easy from the circumstances of her illness, which to many fans were no longer simply rumors.

The unclear details of Easy‘s production are further obscured in its artwork. Of all the albums released by Motown up to that point, Easy was the first to include an image of the performers on the cover that was not a photograph. The cover instead features a tightly framed painting of Terrell and Gaye. The attire and hairstyles suggest that the painting is based on an alternate take from the photo session that produced the cover of You’re All I Need. The back cover of Easy includes no artist photo or liner notes, which is unusual for Motown releases of the period. The sparse layout includes just the album title treatment, the track titles, and recommendations of other Motown releases. The overall presentation seems intended to maximize the nearly exhausted well of material available to Motown, and to distance Easy from the circumstances of her illness, which to many fans were no longer simply rumors.

Within months of Terrell’s death in 1970, Motown released a greatest hits compilation of her duets with Gaye, in sparsely designed packaging that made no reference to Terrell’s passing. Terrell’s brief life naturally leads to speculation about what could have been. Regardless of Motown’s motives and inconsistent methods, it cannot be understated that their promotion of Tammi Terrell’s music provided her with access to health care that likely prolonged her life and gave her a chance to experience fame, even if from a hospital room.

I like Tammi Terrell activities. Terrell’s illness didn’t end her presence on the charts. In an interview with Ebony in late 1969, Terrell mentions that Motown was paying for her treatment, including eight surgeries and extensive rehabilitation. May god bless Tammi Terrell. Thanks