On Radio: The Influence of Comedy Podcasts on TV Narrative, Production, and Cross-Promotion

Post by Mark Lashley, La Salle University.

Post by Mark Lashley, La Salle University.

If you’ve been enjoying television comedy over the past several years, you likely owe a debt of gratitude to a wholly different production form: the podcast.

Podcasts have existed in their current form for well over a decade now, and have been much discussed as a technological form and an industrial challenge. Last year the format got perhaps its largest mass exposure ever, with the success of the docu-series Serial, an absolute sensation that was influenced by some of the finer elements of true crime TV and long form radio production techniques. There have been a number of popular podcasts in many other genres, like sports (The B.S. Report), technology (TED Radio Hour), and business (Planet Money), each of which can be found tucked into its little niche on the iTunes charts.

But I would argue, the unbridled cachet of something like Serial excepted, that the biggest cultural impact of the podcasting revolution, such as it is, has come from comedy. A cursory glance at the iTunes charts in the comedy category reveals a host of comic talent that would be familiar to nearly every TV fan in 2015: Marc Maron, Aisha Tyler, Bill Burr, John Oliver, Chelsea Peretti, Dan Harmon. These comics are joined by other comedy podcasters who have made their bones in screenwriting, local radio, improv theater, and even YouTube. While the technological ease of podcasting has allowed inroads for all kinds of talent to reach increasingly segmented audiences, comedians have reaped the greatest televisual benefits in a media landscape that we have come to accept as both post-television and, almost unquestionably, post-radio.

Take Maron as an example. The 51-year-old standup has widely credited podcasting (in his act, his book, and his podcast itself, WTF With Marc Maron) with saving his stagnant career. Cable network IFC developed a starring sitcom vehicle for Maron (cleverly titled Maron), which features the comic as a fictionalized version of himself, a comedian and podcaster, and which draws heavily on personal stories Maron had shared with his WTF audience. The show has been successful enough to advance to a third season, which premieres in May. Maron was certainly a known commodity as a comic before he began his podcast in 2009, but Maron is undoubtedly a career zenith, and owes its existence to the podcast’s success. In other cases, like in the case of Joe Rogan’s The Joe Rogan Experience (routinely near the top of the iTunes’s rankings), the podcast’s success owes far more to its host’s TV credits. And Rogan has plenty of those, from Newsradio, to Fear Factor, to his current role as UFC commentator.

Take Maron as an example. The 51-year-old standup has widely credited podcasting (in his act, his book, and his podcast itself, WTF With Marc Maron) with saving his stagnant career. Cable network IFC developed a starring sitcom vehicle for Maron (cleverly titled Maron), which features the comic as a fictionalized version of himself, a comedian and podcaster, and which draws heavily on personal stories Maron had shared with his WTF audience. The show has been successful enough to advance to a third season, which premieres in May. Maron was certainly a known commodity as a comic before he began his podcast in 2009, but Maron is undoubtedly a career zenith, and owes its existence to the podcast’s success. In other cases, like in the case of Joe Rogan’s The Joe Rogan Experience (routinely near the top of the iTunes’s rankings), the podcast’s success owes far more to its host’s TV credits. And Rogan has plenty of those, from Newsradio, to Fear Factor, to his current role as UFC commentator.

What I think is most fascinating about this reciprocal influence between the arenas of podcasting and television are the narrative challenges (and opportunities) that come from translating one to the other. And on this count there are several podcast-to-TV properties that have had both critical and commercial success. In the case of Maron, the writing staff has whittled down years of Maron’s musings about his personal life, personal history, and personal neuroses (delivered in an extemporaneous monologue in the first ten minutes of each WTF episode) to a series of fairly average, wholly recognizable 22-minute sitcom episodes. WTF listeners know more about Maron’s outlook on the world than they probably ever cared to hear. In the resulting television product, Maron’s perspective is acted out and contextualized with re-enacted versions of those rants serving as de facto narration. It’s a far different approach to the same material. Some of the 200,000 regular WTF listeners may feel that the sitcom format neuters Maron’s delivery or diminishes the parasocial effect of engaging with the host’s current life crises twice a week for years on end; others may feel the sitcom effectively cuts Maron’s ranting off at a more appropriate juncture (it’s not uncommon for fans or other comedians to profess to loving WTF “except for the first ten minutes”).

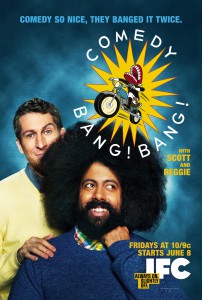

Another of the most popular comedy podcasts, Comedy Bang! Bang!, has also made the transition to television (also on IFC, now in its fourth season). Unlike WTF, which is primarily an interview show outside of Maron’s monologue, the podcast version of CBB is essentially an improvisational showcase for comedians of various backgrounds. Framed as an interview program, CBB typically begins with host Scott Aukerman talking with a celebrity guest. Soon enough, the show is interrupted by at least one other guest, a skilled improviser performing in character in an attempt to derail the proceedings. Very little about the character’s personality is known to the other participants ahead of time. The results are often very funny, sometimes fall flat, and are never in any way constricted; the format of the show is incredibly loose with episodes stretching from 45 minutes to upwards of two hours, depending on when Aukerman decides to rein things in. In 2012, the IFC version of the show was developed, and included major celebrity guests (some of whom had appeared on the podcast), along with recurring characters from the audio version. The CBB television show faces significant narrative challenges in its adaptation, especially considering the fact that a typical episode must be delivered in under 25% of the podcast’s running time. In the adaptation, Aukerman has tried to remain true to the improvisational roots of the podcast. Clearly the appearances of the celebrities and guest characters are edited down from longer, looser improv sessions, but the show has taken advantage of the televisual format to include produced sketches, narrative framing devices, and musical elements (featuring comedian and bandleader Reggie Watts).

Another of the most popular comedy podcasts, Comedy Bang! Bang!, has also made the transition to television (also on IFC, now in its fourth season). Unlike WTF, which is primarily an interview show outside of Maron’s monologue, the podcast version of CBB is essentially an improvisational showcase for comedians of various backgrounds. Framed as an interview program, CBB typically begins with host Scott Aukerman talking with a celebrity guest. Soon enough, the show is interrupted by at least one other guest, a skilled improviser performing in character in an attempt to derail the proceedings. Very little about the character’s personality is known to the other participants ahead of time. The results are often very funny, sometimes fall flat, and are never in any way constricted; the format of the show is incredibly loose with episodes stretching from 45 minutes to upwards of two hours, depending on when Aukerman decides to rein things in. In 2012, the IFC version of the show was developed, and included major celebrity guests (some of whom had appeared on the podcast), along with recurring characters from the audio version. The CBB television show faces significant narrative challenges in its adaptation, especially considering the fact that a typical episode must be delivered in under 25% of the podcast’s running time. In the adaptation, Aukerman has tried to remain true to the improvisational roots of the podcast. Clearly the appearances of the celebrities and guest characters are edited down from longer, looser improv sessions, but the show has taken advantage of the televisual format to include produced sketches, narrative framing devices, and musical elements (featuring comedian and bandleader Reggie Watts).

In addition to these more direct adaptations (of which I could also mention TBS’s failed, though critically well-received Pete Holmes Show), podcasting’s influence on television comedy is felt in more subtle ways. Lost in the recent shuffle of late night Comedy Central hosts is the continued success of Chris Hardwick’s @midnight, a panel show meant to skewer web culture that features three comedian guests each night, many of whom (like Hardwick himself) have had a great deal of success in podcasting, and who use the show’s promotional opportunity to drive traffic to their online offerings. Some of the most frequent guests on @midnight include Doug Benson, Nikki Glaser, Paul Scheer, and Kumail Nanjiani, who have all promoted their popular podcasts on the show (Doug Loves Movies, You Had to Be There, How Did This Get Made?, and The Indoor Kids, respectively). The ABC-Univision collaborative cable venture Fusion has had modest success with one of its first original series No, You Shut Up, featuring comedy podcast all-star Paul F. Tompkins (CBB, The Pod F. Tompcast, Spontaneanation, among others) improvising with fellow comedians and puppets from Henson Alternative (an offshoot of the Jim Henson Company). Comedy Central’s popular Review stars comedian Andy Daly, who is well known among podcast fans for his improvised appearances on dozens of shows. USA’s Playing House features comedians Lennon Parham and Jessica St. Clair who honed their skills through character work on scores of podcast episodes. The list could go on.

In addition to these more direct adaptations (of which I could also mention TBS’s failed, though critically well-received Pete Holmes Show), podcasting’s influence on television comedy is felt in more subtle ways. Lost in the recent shuffle of late night Comedy Central hosts is the continued success of Chris Hardwick’s @midnight, a panel show meant to skewer web culture that features three comedian guests each night, many of whom (like Hardwick himself) have had a great deal of success in podcasting, and who use the show’s promotional opportunity to drive traffic to their online offerings. Some of the most frequent guests on @midnight include Doug Benson, Nikki Glaser, Paul Scheer, and Kumail Nanjiani, who have all promoted their popular podcasts on the show (Doug Loves Movies, You Had to Be There, How Did This Get Made?, and The Indoor Kids, respectively). The ABC-Univision collaborative cable venture Fusion has had modest success with one of its first original series No, You Shut Up, featuring comedy podcast all-star Paul F. Tompkins (CBB, The Pod F. Tompcast, Spontaneanation, among others) improvising with fellow comedians and puppets from Henson Alternative (an offshoot of the Jim Henson Company). Comedy Central’s popular Review stars comedian Andy Daly, who is well known among podcast fans for his improvised appearances on dozens of shows. USA’s Playing House features comedians Lennon Parham and Jessica St. Clair who honed their skills through character work on scores of podcast episodes. The list could go on.

The influence and overlap between the worlds of podcasting and television (and live comedy) is expanding as visual and audio media continue to fragment. Issues of narrative construction and narrative influence are ripe for questioning, as are issues of economic viability and the longevity of both of these forms as the landscape continues to change. Additionally, the cross-pollination of talent between these forms could lead to interesting transmedia inquiries. To my mind, it’s heartening that, in just the past half-decade or so, many more prospects have developed for varied comedic voices, and that a burgeoning format like the podcast has incubated many of those opportunities.