Honoring Hilmes: Strange Report

Post by Jonathan Bignell, University of Reading

Post by Jonathan Bignell, University of Reading

This is the ninth post in our “Honoring Hilmes” series, celebrating the career and legacy of Michele Hilmes on the occasion of her retirement.

The aspect of Michele Hilmes’ work that has most affected me is her brilliant historical analysis of the related but distinct broadcasting traditions of Britain and the USA in Network Nations (2011). She has documented and evaluated their long-standing links, but also shown how each has defined itself by repudiating the other. The lesson that I have learned from Michele is that when we look closely at the detail of history, there are always more complex and more interesting things to discover. This post is just a brief example of such a discovery. What looks like a British show imitating an American format turns out to be a US production made abroad. Its conventionally transatlantic casting includes a Lithuanian playing an ex-patriate Minnesotan, and alongside the “swinging London” of the mid-1960s we see the decaying Victorian houses of the inner city.

My former colleague Billy Smart kindly gave me Network’s DVD release of the action series Strange Report (1969-70) recently. At first glance, it looks like a rather less successful example of the British action shows that flourished in the 1960s and briefly succeeded across the Atlantic too (as discussed in my 2010 Media History article). British series like The Saint (1962-69), The Avengers (1961-69), and The Champions (1968-69) adopted versions of US industrial organization to make programmes that would be saleable to US networks, by shooting on colour film, on location (British drama was still mainly shot on video in the studio), and with an upbeat “mod” aesthetic.

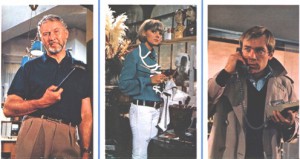

Strange Report seems initially to conform to the format. Each week a retired British Home Office criminologist, Adam Strange (played by Anthony Quayle), solves sensitive cases in which government departments cannot become publicly involved. Strange is aided by a young US Rhodes scholar, Hamlyn Gynt (Kaz Garas), and Strange’s next-door neighbour, the vivacious model-cum-artist Evelyn (Anneke Wills).

But rather than representing international modernity, Strange Report remains surprisingly bound to its London setting. The series was filmed from July 1968 to March 1969 on location in London and at Pinewood Studios outside the city. To solve cases, the methodical and avuncular Strange uses his personal laboratory at his house in the run-down Paddington district, and his cerebral approach is complemented by Gynt’s physical vigour and Evelyn’s familiarity with London’s trendy bohemian culture. The British Film Institute’s excellent online guide, screenonline, notes that: “Locating the show in a recognisably contemporary London allowed the programme to display a degree of realism and authenticity unusual for its genre.” One episode is an investigation of violent student demonstrations (shortly after the revolutionary events of May 1968 in Paris), while another is about immigration and racism (in 1967 the British Member of Parliament, Enoch Powell, infamously predicted “rivers of blood” after immigration from Britain’s former empire increased). Stylish action-adventure series rarely addressed such concerns. Although the middle-class, middle-aged Strange tamed these issues by the end of each episode, the disparate quasi-family of protagonists seem closely engaged in their milieu.

Two of the featured actors were British: Quayle trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and was a member of the respected Old Vic theatre company from 1932. After army service in World War II he was a leading actor and director at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, which would later become the Royal Shakespeare Company. He featured in the British war films Ice Cold in Alex (1958) and The Guns of Navarone (1961), as well as the epic Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Aneke Wills featured in a TV adaptation of British children’s novel The Railway Children in 1957, and in Doctor Who from 1966-67 as companion to Doctors William Hartnell and Patrick Troughton. These were iconic English actors in significant British film and television roles. But Kaz Garas who played Strange’s youthful American sidekick was born in Lithuania, not the USA, though he based his career there.

The most interesting aspect of this transnational programme is that its executive producer was Norman Felton, best known as the creator and producer of US network series Dr. Kildare (1961-66), The Lieutenant (1963-64), and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68). Felton was a transatlantic figure himself; he was born in London, but his family migrated to the US in 1929. His parents returned but Felton stayed in the USA, won a playwriting fellowship to the University of Iowa, and worked in theatre, then radio at NBC. In the 1950s he worked in TV in New York, writing and directing for live anthology dramas like Alcoa Hour (1955-57), Goodyear Playhouse (1955-57), and Studio One (1948-58), and by end of the decade he was executive producer of Playhouse 90 (1956-60). He became MGM’s director of television, and formed the company that made Strange Report, Arena Productions, in 1961.

The most interesting aspect of this transnational programme is that its executive producer was Norman Felton, best known as the creator and producer of US network series Dr. Kildare (1961-66), The Lieutenant (1963-64), and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68). Felton was a transatlantic figure himself; he was born in London, but his family migrated to the US in 1929. His parents returned but Felton stayed in the USA, won a playwriting fellowship to the University of Iowa, and worked in theatre, then radio at NBC. In the 1950s he worked in TV in New York, writing and directing for live anthology dramas like Alcoa Hour (1955-57), Goodyear Playhouse (1955-57), and Studio One (1948-58), and by end of the decade he was executive producer of Playhouse 90 (1956-60). He became MGM’s director of television, and formed the company that made Strange Report, Arena Productions, in 1961.

Felton was in London during production in 1969, and the British ITV network broadcast Strange Report that year. The intention was that production partner NBC would screen it in the USA and that a second, US-set series would be made in which the characters would relocate across the Atlantic. In January 1971, NBC got around to screening Strange Report on Fridays from 10:00 to 11:00 p.m. EST until September, but the second series was never made, apparently because Quayle and Wills did not want to travel. The strange story of Strange Report complicates the history of British drama and its relationships with the American market, offshore co-production involving the US networks, and the innovative collaborations between British and American personnel in the 1960s. And this is just the short version of the story….

This is a fascinating piece on a series that I had never heard of! Thanks for bringing it to scholarly attention, Jonathan. Another example of the complex set of relationships that constitute transnational TV.