Digital Tools for Television Historiography, Part I

Post by Elana Levine, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Post by Elana Levine, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

This is the first in a series of posts detailing my use of digital tools in a television history project.

When I was researching and writing my dissertation at the turn of the 21st century, analog tools were my friend. Because my project was a history of American entertainment television in the 1970s, I drew upon a wide range of source materials: manuscript archives of TV writers, producers, sponsors, and trade organizations; legislative and court proceedings; popular and trade press articles; many episodes of ‘70s TV; and secondary sources in the form of scholarly and popular books and articles. The archive I amassed took up a lot of space: photocopies and print-outs of articles, found in the library stacks or on microfilm; VHS tape after VHS tape of episodes recorded from syndicated reruns; and stacks and stacks of 3X5 notecards, on which I would take notes on my materials. I gathered this research chapter by chapter and so, as it would come time to write each one, I would sit on the floor and make piles in a circle around me, sorting note cards and photocopies into topics or themes, figuring out an organizing logic that built a structure and an argument out of my mountains of evidence. It. Was. Awesome.

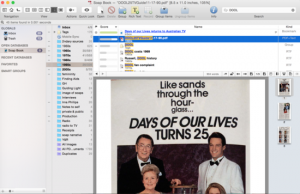

As I turned that dissertation into a book over the coming years, and worked on other, less voluminous projects, I stuck pretty closely to my tried and true workflow, though the additions of TV series on DVD and, eventually, of YouTube, began to obviate my need for the stacks of VHS tapes. Around 2008, I began to research a new historical project, one that I intended to spend many years pursuing and that promised to yield a larger archive than I’d managed previously. This project, a production and reception history of US daytime television soap opera, would traverse more than 60 years of broadcast history and would deal with a genre in which multiple programs had aired daily episodes over decades. Still, as I began my research, I continued most of my earlier methods, amassing photocopies and notes, which I was by then writing as word-processor documents rather than handwritten index cards. By late 2012, I was thinking about how to turn these new mountains of research materials into chapters. And I freaked out.

Sitting amidst piles of paper on the floor seemed impractical—there was so, so much of it—and I was technologically savvy enough to realize that printing out my word-processed materials would be both inefficient and wasteful. So I began to investigate tools for managing historical research materials digitally. Eventually, I settled on a data management system called DevonThink. I chose DevonThink for a number of reasons, but mostly because it would allow me to perform optical character recognition (OCR) to make my many materials fully searchable. This was a crucial need, especially because I would be imposing a structure on my research after having built my archive over years and from multiple historical periods. It would be impossible for me to recall exactly what information I had about which topics; I needed to outsource that work to the software.

This required that I digitize my paper archive, which I did, over time, with help. My ongoing archival research became about scanning rather than photocopying (using on-site scanners or a smartphone app, JotNot, that has served me well). And I began to generate all of my new notes within DevonThink, rather than having to import documents created elsewhere. Several years into using DevonThink, I still have only a partial sense of its capabilities, but I see this not as a problem but as a way of making the software fit my needs. (Others have detailed their use of the software for historical projects.) I have learned it as I’ve used it and have only figured out its features as I’ve realized I needed them. There are many ways to tag or label or take notes on materials, some of which I use. But, ideally, the fact that most of my materials are searchable makes generating this sort of metadata less essential. I rely heavily on the highlighting feature to note key passages in materials that I might want to quote from or cite. And I’ve experimented with using the software’s colored labeling system to help me keep track of which materials I have read and processed and which I have not.

Because I have figured out its utility as I’ve gone along, I’ve made some choices that I might make differently for another project. I initially put materials into folders (what DevonThink calls “Groups”) before realizing that was more processing labor than I needed to expend. So I settled for separating my materials into decades, but have taken advantage of a useful feature that “duplicates” a file into multiple groups to make sure I put a piece of evidence that spans time periods into the various places I might want to consider it. I have settled into some file-naming practices, but would be more consistent about this on another go-round. I know I am not using the software to its full capacity, but I am making it work in ways that supplement and enable my work process, exactly what I need a digital tool to do.

Because I have figured out its utility as I’ve gone along, I’ve made some choices that I might make differently for another project. I initially put materials into folders (what DevonThink calls “Groups”) before realizing that was more processing labor than I needed to expend. So I settled for separating my materials into decades, but have taken advantage of a useful feature that “duplicates” a file into multiple groups to make sure I put a piece of evidence that spans time periods into the various places I might want to consider it. I have settled into some file-naming practices, but would be more consistent about this on another go-round. I know I am not using the software to its full capacity, but I am making it work in ways that supplement and enable my work process, exactly what I need a digital tool to do.

In many respects, my workflow remains rather similar to my old, analog ways, in that I still spend long hours reading through all of the materials, but now I sort them into digital rather than physical piles (a process that involves another piece of software, which I will explain in my next post). In writing media history from a cultural studies perspective, one necessarily juggles a reconstruction of the events of the past with analyses of discourses and images and ideas. I don’t think there is a way to do that interpretive work without the time-consuming and pleasurable labor of reading and thinking, of sorting and categorizing, of articulating to each other that which a casual glance—or a metadata search—cannot on its own accomplish.

But having at my fingertips a quickly searchable database has been invaluable as I write. Because I have read through my hundreds of materials from “the ‘50s,” for instance, I remember that there was a short-lived soap with a divorced woman lead. Its title? Any other information about it? No clue. But within a few keystrokes I can find it—Today Is Ours—and not just access the information about its existence (which perhaps an internet search could also elicit) but find the memo I have of the producers discussing its social relevance, and the Variety review that shares a few key lines of dialogue. OCR does not always work perfectly—it is useless on handwritten letters to the editor of TV Guide—but my dual processes of reading through everything and of using searches to find key materials has made me confident that I am not missing sources as I construct my argument and tell my story. It’s a big story to tell, and one that may be feasible largely due to my digital tools.

Great post–thank you! Following your recommendation, I am now also beginning to use DevonThinkPro Office. I use the version that includes ABBYY reader software, which is better OCR software than Adobe Acrobat (Acrobat refuses to OCR my PDFs created from iPhone photos). In DTP, File>Import>Images with OCR lets me import files into DTP and OCR them in large batches–though not quickly, because I use the “accurate” OCR setting.

After importing I can click on the “Word” icon and see immediately in a sidebar which words were found by the OCR. This is key! Some old carbon copies just don’t OCR well (and the word list is full of crazy nonwords), which means a later search might not locate the document. So I invented a label (an orange dot) that means “Bad OCR,” and I annotate that document in “Spotlight comments” with more searchable terms and phrases so that it will be found in a later search. I hope that labeling some documents “Bad OCR” will also help me identify which documents might need double checking if a search doesn’t find them.

Thanks, Elana, for helping us index card junkies go digital!

Cynthia, I love this idea about the Bad OCR label! Just today I was looking for an article I knew I had but it wasn’t turning up in my search. I eventually found it, but it made me think about what I might be missing because of my (pretty common) Bad OCR documents. I think I will start using a system similar to yours as I read through my next batch of materials. Good to know DTP is doing OCR better than Acrobat; I use both but will tend toward the former now (even though I don’t plan to collect too many more sources!).

Yes, this retrieval issue is what concerns me about digital search. If the document doesn’t come up–whether because of bad OCR or a bad search term–I might not remember the document exists! So why collect it if I can’t retrieve it? I am taking more notes in DTP than I expected precisely to create searchable text for the “bad OCR” documents–and even the “good OCR” ones!

For better OCR in DTP, be sure to go to Preferences>OCR and select “accurate.” Slower but, presumably, more accurate!

Elana and Cynthia, this is a great discussion. Thanks!! This Macworld article, although a few years old now, provides a helpful analysis of the file size and accuracy of different OCR software. Author’s conclusion is that Acrobat Pro is the least accurate. Best configuration seems to be ABBYY/DevonThink Pro Office scanning at 300dpi in grayscale at medium compression: http://www.macworld.com/article/2043857/secrets-of-the-paperless-office-optimizing-ocr.html

For thousands of years, dating back to before the library of Alexandria, recording was done in writing and on paper, leather or parchment. Only since a few decades do we “trust” magnetic and optical media with our information. However, recording formats as well as technology change decade after decade after decade. There already are lots of “vernacular” media that even specialists cannot reliably read. To really talk in terms of historical time frames, like centuries or millenia, we urgently need a constant (!) perpetual migration strategy for each media type and recording format to “copy” it onto the next new technology and then the next, the next and so on. It already seems foreseeable that libraries will have more work to do with the “immaterial” storage technologies than they once had cataloging and storing books!