Crowdfunding: Looking Beyond Kickstarter

Post by Patryk Galuszka and Blanka Brzozowska, University of Lodz

Post by Patryk Galuszka and Blanka Brzozowska, University of Lodz

This post is part of a partnership with the International Journal of Cultural Studies, where authors of newly published articles extend their arguments here on Antenna.

Until recently crowdfunding mostly drew the attention of economists, who attempted to measure the efficiency of this new form of financing, and lawyers, who discussed its regulation. Viewing crowdfunding from the perspectives of cultural and media studies not only enhances our understanding of the phenomenon, but also has the potential to make a contribution to research into the relationships between artists and fans. However, crowdfunding poses quite a challenge for researchers. For one thing, there are several models of crowdfunding, each assigning different roles to project initiators and contributors. It is reasonable to assume that not all of an estimated number of over 1,000 platforms worldwide are clones of Kickstarter. In addition, artists’ statuses are different–we should take into account that the process of crowdfunding conducted by a star with a global following will take a very different form than a collection effort initiated by a debutant who in the beginning can count only on him or herself and family and friends.

MegaTotal (see Figure 1), the crowdfunding platform that is the subject of our analysis, operates according to a different model from that of Kickstarter.

Figure 1. MegaTotal.

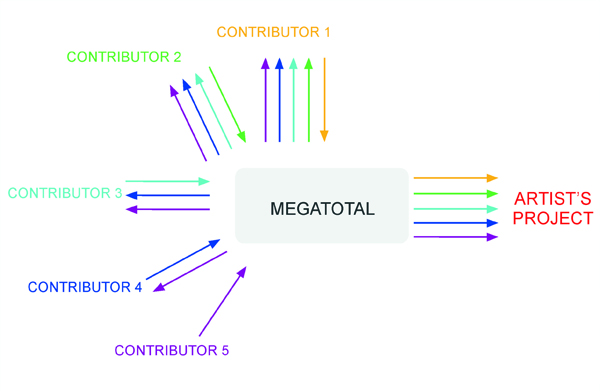

The most important difference between MegaTotal and Kickstarter is the application in the former of investment mechanisms resulting in people who support popular projects receiving a return on their investment. In practice, this means that each and every payment (except for the first) is subdivided into two equal parts, where one part goes to the project initiator and the other is distributed among earlier contributors in proportion to their participation in the project (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flow of capital between contributors and project initiators on MegaTotal. Each contributor’s payments and equity stake is represented by different color. Contributor 1 captures part of the funds paid by all the other contributors. Other contributors correspondingly enjoy proportionally lower capital flows. Source: The rise of fanvestors: A study of a crowdfunding community, by Patryk Galuszka and Victor Bystrov. First Monday, Volume 19, Number 5 – 5 May 2014

In effect, every contribution increases the account of the project, but also determines the position of the backer on the list of project “shareholders” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. List of shareholders in this project

The flow of resources takes place in real time, which means that “profits” are transferred to the accounts of contributors in the service the moment the given project attracts successive contributors. As a result of this mechanism, contributors have additional motivation that is not present in donation-based and reward-based crowdfunding.

It may be said that crowdfunding incorporates qualities originating on a base of fan activity, such as claims to the rights to artist’s work and the striving to influence its development as derived from that right. Such qualities, however, presently go beyond the framework of fandom and mold a new dimension of consumer culture as such. Regardless of whether contributors can be termed as fans or not, analysis of crowdfunding should take into account the possibility of their active participation in the process of creating a culture product. What is being discussed is a phenomenon that is perhaps not totally transforming the production system (at least not at this time), but is presently decidedly behind a change in relations with consumers and an understanding of the role of the artist as such. The assumption that the currency of crowdfunding is the emotional involvement of consumers–not just their attention attracted thanks to efficient promotion–means that the new model cannot be easily compared to any standard whose foundation is the traditional marketing model.

Artists must find themselves within this new situation and simultaneously see the promotional and distribution potential of crowdfunding. To quote Ted Hope, advocate of America’s independent cinema movement and Executive Director of the San Francisco Film Society:

Our interviews with musicians who use MegaTotal support that argument. Crowdfunding requires that the project initiators themselves have specific aptitude and change their approach to the process of creating, promoting and distributing culture products. This corresponds very well with the argument that today artists (and those who do not engage in crowdfunding) are required to embrace entrepreneurial skills. Those artists who find this approach problematic should probably stay away from crowdfunding.

It should be noted that the character of the change taking place is more one of awareness than technology. This creates a new division among creators, negating the traditional one onto mainstream (a model in which the artist is passive and the label/publisher/studio divests him or her of freedom, but in exchange concerns itself with distribution and promotion) and “indie” (a model in which the artist is more active and fights for his or her independence, but often at the cost of a lack of publicity and counting on the loyalty of fans). The new division, though dictated by digital technology, primarily necessitates assimilation by artists and acceptance of a new attitude. The statement may be risked that the greatest potential in the development of independent creativity is actually hidden in this new model for promotion and distribution based on close contact with the consumer. It is thanks to the consumer that texts from the realm of “indie” can reach a significantly larger audience without losing anything of their “independent” character.

[For the full article, see Patryk Galuszka and Blanka Brzozowska, “Crowdfunding: Towards a redefinition of the artist’s role – the case of MegaTotal,” forthcoming in International Journal of Cultural Studies. Currently available as an OnlineFirst publication: http://ics.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/05/11/1367877915586304.abstract]