Public Stadium Financing: The World’s Greatest “Save Our Show” Campaign

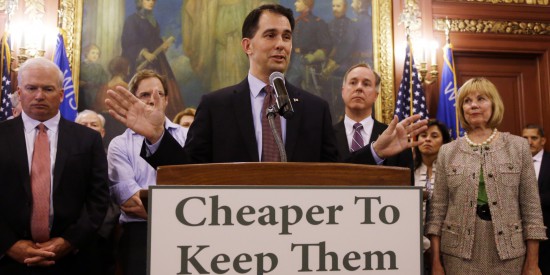

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker presenting a deal to finance a new Milwaukee Bucks arena with public funds.

Post by Michael Z. Newman, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

The pending deal to keep the Milwaukee Bucks in Milwaukee is only the most recent instance of local and state governments in the U.S. agreeing to subsidize major league sports facilities. The NBA team’s owners, who are richer than God, bought the team pledging to keep it in town. The league has made clear that the Bucks can’t stay without a new arena, so the owners threatened to move them absent public financing for a portion of the costs. This has followed a standard script in American sports: the politicians who hold the purse strings submit to this extortion lest their constituents blame them for the loss of a beloved team. The elected leaders stage the political theater of touting the economic benefits of new sports facilities to local economies (anyone well informed knows better). Those with an interest in keeping the team–fans serious and casual, civic pride boosters, local media who benefit from having a team to cover–publicly support saving the team.

Others point out the shameless corporate welfare. As it is playing out in Milwaukee, the deal to finance the arena involves the state diverting $4 million annually until 2035 from payments to Milwaukee County to pay construction costs. Milwaukee is one of the poorest and most racially segregated cities in America, with a myriad of problems that several million dollars a year could help address. That money is going instead to a project that will be certain to further enrich the team’s owners and the league, and to return little more economically to Milwaukee than a small number of jobs to last only as long as the building’s construction. Supporters of the deal are excited that the new arena will be part of an urban revitalization, developing currently vacant downtown property. It’s certainly telling that hundreds of millions of public funds for urban revitalization somehow materializes when the economic beneficiaries are out-of-town fat cats threatening to take away your basketball team.

As a matter of economic policy, it’s easy to see that these deals stink. Owners of major league sports teams can afford to build new facilities, but local governments are willing to pay so it would be foolish for owners to pass on that. Governments pony up because of competition among cities: in each league, there are fewer teams than there are cities that could support them. Public funding is a subsidy to a thriving private business that doesn’t need it.

But what if we see these subsidies as a matter of cultural policy? The issue isn’t usually framed that way, maybe because sports doesn’t seem like a culture industry, but these handouts effectively function to promote a form of local culture, and thinking of this is a matter of cultural rather than economic policy might help us appreciate what is at stake in these political debates.

Actually what these lavish handouts promote and protect is the experience of watching a local sports team and following them day by day, season by season. This involves mainly viewing them on TV and talking about it, and participating in the activities of fandom: dressing up in fan apparel, debating with other fans, and sometimes coming together at a public event where the team competes. This event, the game, is where the pricey new arena or stadium comes in: it’s essentially a TV studio with a big paying live audience where the show is produced. Watching the show requires a subscription to a special cable channel (a regional sports network), going to the event requires buying a typically expensive ticket, and participating in this fandom often winds up costing fans some money; it’s a consumer experience, like so much of our cultural life. Live sports is a big reason why many cable subscribers keep paying that monthly bill. That’s what makes sports so powerful: the product has a huge devoted media audience willing to spend its money. All of this is deeply shaped by collective public affect, as fans together experience the highs and lows, the anticipation and disappointment, of the drama of sports. “Save our team” is also “save our show.” It’s “save our culture.”

Cultural policy is usually associated with the arts and with national identity. For instance, Canadian cultural policy protects the Canadian culture industries against competition from American products through quotas, subsidies, and other means. Its logic is to maintain the nation’s distinct identity by representing Canada to Canadians, protecting local cultural industries in the process. To the extent that sports teams are a crucial component of local identities–and talk of Red Sox Nation, Packers Nation, etc., suggest they are very crucial–public support for sports teams protects these identities by supporting the consumer culture at their center. The idea that sports facilities help the economy is a veil of justification giving legitimacy to this cultural agenda. The real importance of the deal is its support for a form of patriotism to a team and investment in allegiance to it. That’s what the people refuse to give up.

As a cultural policy, there are some things to cheer and others to jeer about local sports teams getting huge handouts from the public. On the positive side of the ledger, sports really is central to a great many people’s identities and to the identities of modern places. It would be a loss to see the basketball team depart. No one is ushering them out. But this is a thin reed on which to hang such massive investment, and there is a downside too.

If hundreds of millions in state funding is going to support a cultural policy during this age of austerity, when there is plenty of need to go around, when schools are underfunded and poverty limits so many people’s opportunities, we ought to consider pretty carefully what kind of culture the public should support. Major league sports is lots of fun to watch and follow as a fan, but it’s also deeply flawed ideologically. Spectator sports of the kind that draws big ratings week after week has many appeals, and one appeal central to its values and meanings is hegemonic masculinity.

There is an audience for women’s sports, but the fact that ordinary usage modifies any sports played by women as women’s sports speaks loudly about the gender politics involved. In a society of changing gender roles and continual crises of masculinity, sports is a bastion of traditional gender performance in which men are celebrated for their physical strength, endurance, agility, and skill, their stoicism and toughness, their adherence to a blue-collar code of hard work. Major league sports is one of the last institutions in society in which overt gender segregation goes totally unquestioned. All of the culture surrounding sports, from the conventions of media coverage to the sanctioned activities of fandom, are masculinized. In major league sports in America, women are seldom even permitted to narrate the action as play-by-play voices or sit behind the desk on a pre-game or halftime broadcast trading observations. Women participate in major league fandom but on terms set by men. The value of sports as a media genre, and thus as an economic juggernaut, is largely its ability to command men’s attention, though leagues have recognized that appealing to women helps them as well.

I’m not so naive as to imagine a public deliberation about the cultural policy of supporting sports teams in which hegemonic masculinity is the key term. What seems more possible is that by recognizing these subsidies as following a cultural rather than an economic logic, the people and their elected representatives might weigh the real benefits of supporting such expenditures against the enormous, and I would say unacceptable, costs. I doubt it, though. “Save our team” investments may be too deeply affective, and too much tied up in matters of identity, to be a subject for rational debate.

Michael Z. Newman has lived in Milwaukee for 13 years and has yet to attend a Bucks game, but enjoys the occasional summer afternoon at the publicly-financed Miller Park.

As a Bucks fan who has gone to nearly 100 games since the late ’80s…I can’t really argue with most of this. 🙂 Although the Bucks do generate a substantial amount of state income tax revenue that will go into the general fund, so there is an economic impact that goes beyond short-term construction jobs. And from a moral standpoint, basketball is for me less problematic than the WI state religion of football, since basketball players aren’t typically subject to the same kind of traumatic injuries.

In terms of cultural policy, one thing left out of most discussions about the arena is the importance of the NBA to many African-American Wisconsinites, particularly in downtown Milwaukee. NBA viewership nationwide is nearly 50% African-American, and the demographics at Bucks games are hugely different than at the Brewers or Packers games. In a deeply segregated city that has profound disparities in terms of race and income, the Bucks have cultural value as a high-profile, relatively inexpensive entertainment option in downtown Milwaukee that appeals to diverse audiences. Not saying that alone justifies public money, but it’s something to consider.