“Something Into Nothing”: On the Materiality of the Broadcast Archive

Post by Laura LaPlaca, Northwestern University

Post by Laura LaPlaca, Northwestern University

eBay launched when I was seven years old and I bid on a beat-up old pair of Milton Berle’s shoes. I watched episodes of The Texaco Star Theatre over and over again with the shoes perched next to me on the couch. I thought it was incredible that they could be on the television screen and in my living room at the same time – like I had the power to pluck enchanted objects out of fairy tales and keep them for my own.

By the time I graduated from high school, I had just under 3,800 pieces of broadcast memorabilia. As I accumulated each one, I polished it, and labeled it, and learned its story. The history of broadcasting, as I knew it, grew wider and deeper along with the piles on my bedroom floor.

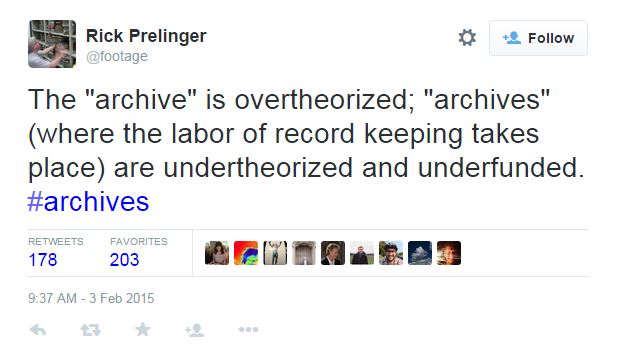

The material relationship I developed with broadcast history as a collector and, eventually, as a media archivist in more formal settings, leads me to balk a little bit when I hear the radio and television archive referred to as “ephemeral.” There are certainly undeniable benefits to emphasizing ephemerality, not least of which is the perpetuation of a sense of urgency; it is imperative that we maintain a high level of alertness as we devise and implement strategies for preventing losses of content. But we tend to emphasize ephemerality to such a degree that we do not discuss the broadcast archive’s extraordinarily expansive physicality at all. Its size and weight, as well as the infrastructures – both physical and intellectual – that support it, too often go unremarked upon. We should recognize that deflecting our attention away from the corporeal mass of the broadcast archive can undermine institutions that need our continual support. I return often to one of archivist Rick Prelinger’s Tweets: “The ‘archive’ is overtheorized; ‘archives’ (where the labor of record keeping takes place) are undertheorized and underfunded. #archives.”

What’s more, fixation on that which is ephemeral – or missing from the archive – dampens the spirit of discovery that so powerfully impels us toward knowledge. An overwhelming majority of the time, researchers walk into archives seeking to corroborate a preexisting thesis. And an overwhelming majority of the time, they walk out of archives feeling as though they did not find “enough.” For them, the archive is lacking – what they need has not been saved. As an archivist, I often find myself imploring researchers to shift their attitude at this moment of resignation, to move past bemoaning the lack and move toward celebrating that which has survived. This is usually the point at which new and different kinds of histories present themselves.

Whenever possible, we should strive to walk into archives with a spark of that collector’s greed that is such a terrific incitement to curiosity. We should let an acquisitive impulse – an open desire to know as much as possible – drive us, so that the archive can inspire, rather than merely support, our work. The process of grabbing on to something material, celebrating its miraculous survival, and then compelling it to dictate its own story is powerful. And when we let the objects come first, the problem is no longer that the archive is found lacking, but that we will never be able to discover everything that the archive has to offer. While this shift in attitude doesn’t change the hard facts of destruction and deterioration (which again, we need to continue to stay apprised of), it does facilitate the circulation of otherwise untold stories and, in this way, works as something of a preservationist tactic in and of itself. Indeed, many objects in archives are not constitutively “ephemeral” at all, but have nevertheless been obscured or erased by our sheer inattention.

Eugenia Farrar

The following is one of my favorite examples of what can happen when an ignored artifact asserts its materiality and cries out to be interrogated. This is the story (in brief) of radio pioneer Eugenia Farrar – the first person to sing over radio waves – and her century-long post-mortem fight against ephemerality.

In the fall of 1907, Farrar visited the Manhattan studio of Lee de Forest, an early radio inventor, to aid in the test of an experimental transmitter. Since de Forest had not yet invented a radio receiver, there would be no way of knowing if the transmission had been successful – and absolutely no record of Farrar’s song. Somewhat sardonically, Farrar approached the curious machine and said, “Here goes something into nothing!”

As she began to sing a rendition of “I Love You Truly,” a popular song of the day, a civil engineer tinkering with the USS Dolphin’s new radiotelephone at the Brooklyn Navy Yard clutched his earpiece and trembled, listening in rapture to what he could only assume was the voice of an angel. The engineer, 19-year-old Oliver Wyckoff, called the papers to report that he had experienced divine communication. The editor on duty dismissed the call as a prank, but – just in case it were true – buried the story on the seventh page of the next morning’s paper.

Lee de Forest

The Farrar story became the stuff of legend: no one could verify Wyckoff’s testimony, de Forest was notoriously fond of claiming credit for dubious innovations, and the broadcast itself had disappeared “into the ether” without a trace. De Forest and Farrar attempted to promote their achievement throughout the early 20th century, but their story faded and was almost entirely forgotten.

In 1966, six decades after having heard the “angel’s” voice, Oliver Wyckoff received a cardboard box containing Farrar’s cremated remains. He left the box unopened on a shelf in his office for years. The extended Wyckoff family inherited the remains, which they respectfully referred to as “The Madame,” and shuffled the box between their closets and garages until 2007. By this point, exactly one hundred years after the historic broadcast, the box itself was on the verge of complete disintegration.

Farrar’s remains were acquisitioned by the Brooklyn Navy Yard Archives and sound artists Melissa Dubbin and Aaron Davidson were commissioned to design an urn to properly contain them. Dubbin and Davidson used phonograph cutting techniques to carve a mid-20th century recording of “I Love You Truly” into a ceramic urn like the grooves on a wax cylinder. Farrar’s post-mortem journey ended with her ashen physical remains protected by the materialized solid form of her voice. The “angel” was interred during a ceremony at the historic Green-Wood Cemetery in 2010.

Perhaps there is no event as “ephemeral” as this forgotten broadcast of “something into nothing,” and no artifact more precarious than an “angel’s” displaced ashes.

Yet the stark materiality of Farrar’s remains, the way that they literally escaped their container and demanded to be attended to, preserved this important story about early radio innovation. Confronted with a tangible object, Dubbin and Davidson, as well as a small cohort of researchers, were incited to reconstruct the long-forgotten events of the fall of 1907, which were widely circulated by the media over a century later alongside coverage of Farrar’s interment ceremony.

I had the rare privilege of hearing the “angel’s voice,” quite on accident, when I was on fellowship at the Library of Congress. I was archiving a collection related to the radio talent program Major Bowes’ Original Amateur Hour – the earliest example of a phone-in voting contest, in the mode of American Idol. I was thrilled when I heard early performances by Frank Sinatra (his voice cracked fantastically), Paul Winchell, and Connie Francis. But I was absolutely stunned to find myself holding the small square form of Eugenia Farrar’s intricately embossed calling card, addressed to Major Bowes himself, requesting a spot on his show. A note from Lee de Forest followed, with a tiny golden radio tower emblazoned on it. I located the tape of the broadcast and listened as Farrar sang “I Love You Truly” in her lilting, distant voice and explained to the audience that, since only one man had heard it the first time around, she was glad to reprise her song “so that it might not be forgotten.”

Although I never saw the urn, Farrar’s words about the persistence of memory conjured the image of her song etched in ceramic, buried beneath the earth, and turned into a material thing. For me, the urn stands in for a whole class of artifacts that are both beautiful and haunting for the very fact of their durability.

Great piece, Laura!

Very nice work!

So many questions here – how did Wyckoff come to be given Farrar’s ashes? How did the Brooklyn Navy Yard Archive have the budget to hire sound artists for this project? Seems like the magic and mystery of early radio continued to linger around Farrar long after her death.

For anyone interested, here is a photo of the urn and the niche she is in at Green-Wood:

https://www.green-wood.com/2013/eugenias-got-a-brand-new-urn/

A photo of a young Wyckoff and more photos of Farrar:

https://www.green-wood.com/2010/voice-angel-transmitted-live-radio/

[…] LaPlaca‘s thoughtful essay — musing on the materiality of this final remaining artifact of a historic broadcast that […]

Hi Ryan –

Farrar and Wyckoff (along with de Forest and others) formed a group called the De Forest Pioneers. They stayed in touch with one another for most of their lives through this group. Farrar had no living descendants (outside of some distant relatives in Sweden that, I believe to this day, have a portrait of her hanging in their home…) and she willed her remains to Wyckoff.

I am not sure if the Brooklyn Navy Yard Archives compensated Dubbin and Davidson for their work or not. These artists had a prior interest in Farrar’s story because their studio is also located at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, very near the site where Wyckoff was working when he heard the first transmission. In 2008, prior to learning of the existence of the remains, they orchestrated a sound performance from Wyckoff’s reception site in which “I Love You Truly” was performed live 101 years after the date of the original broadcast. This live performance, as well as the later creation of the urn, together constitute their piece “You Love Me Truly.” More info about the piece here : http://dubbin-davidson.com/You-Love-Me-Truly

Dubbin and Davidson had contacted the Library of Congress one at least one occasion looking for a recording of Farrar singing “I Love You Truly” to play at the live event/inscribe on the urn, but prior to my discovery of the Major Bowes’ broadcast there were none available. Unfortunately, the urn was interred a few years prior to the discovery of the radio episode.

Thanks for your questions!

Thanks very much 🙂

Great post, thank you! I think it good advice to emerging scholars to explore archival resources to find untold stories. I have always likened my research method to that of the drunk searching for keys under the streetlight–because that is where the light is! I go to the archives not knowing what I will find and I look for stories to tell, rather than go to the archives to document a story I’ve already decided to tell.

But I wonder if one reason many scholars tend to search archives with too specific goals (and thus be disappointed with the lack of documentation) is because they must come up with grant proposals, etc., more specific, perhaps, than “I’d like to see what is in those boxes”! It may also be worth discussing how archival resources could described, catalogued, etc., in ways so that scholars can better identify the collections that would be worth the travel expense–the major obstacle for most scholars doing archival research.

BTW, I was under the (mistaken?) impression that DeForest’s early transmission happened at his home in Riverdale (the Bronx). I tend to claim this to my classes, held just a mile or so from DeForest’s former mansion, but I may be misleading them in the hope of interesting them in the past!