More Than a (Small/White/Cisgender) Woman: Images of Non-Normative Women in Sports

Post by Jennifer Lynn Jones, Indiana University

Every year I look forward to ESPN Magazine’s “Body Issue,” an interesting if somewhat uneven antidote to Sports Illustrated’s “Swimsuit Issue.” Out now, the issue ostensibly serves as a reframing of the body according to the demands of a specific sport, celebrating bodies “for what they can do, rather than how closely they adhere to prevailing beauty standards.” It typically features female and male athletes posing naked in the midst of activity, discussing their relationship to their body and their sport. Past editions have included sections contrasting the average size and shape of athletes in different sports, charting not only the range but also the value of bodily variation in athletes.

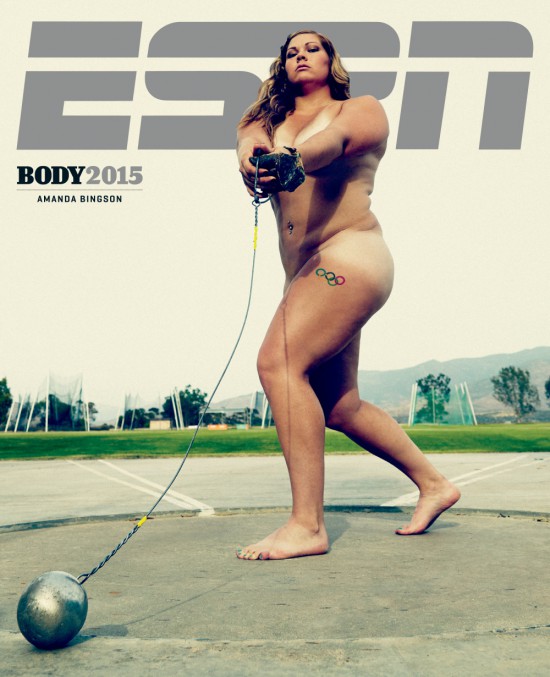

This year’s edition appeared just a few weeks ago, and this is the image that got me excited to see it.

Amanda Bingson is a record-holding hammer thrower from Nevada. She competed at the 2012 Olympics and is a professional athlete with USA Track and Field. And just look at her here! Big! Strong! Tough! Some might say thick but Bingson also calls her body “dense.” The skin rolls on the cover photo don’t seem inhibit her abilities, nor does the cellulite on her hip in the interior spread.

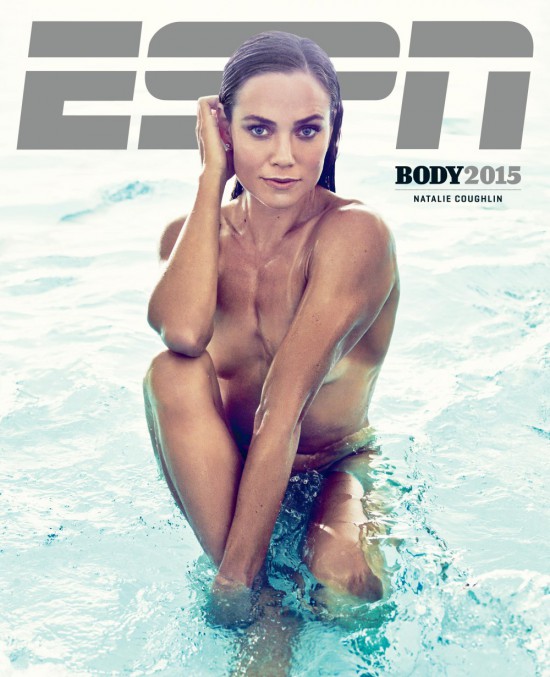

But this is the only cover I found on the newsstand.

Natalie Coughlin is one of the most successful swimmers in the world, has medaled in every major competition in her field, and even holds the record for the most medals received at one Olympics in her 2008 appearance. There’s no question of her abilities; the question here is who ESPN Magazine chooses to feature how and where. For special issues with multiple covers, my experience is that newsstand availability reveals what image the magazine believes will sell best, with those predicted to be less popular going out to subscription holders. Newsstand issues therefore wind up being the most normative image, and the logic holds here: a slim, white, blonde female athlete barely engaged in the actual activity of her sport. In contrast to Bingson, Coughlin doesn’t even have to appear “in action” to prove her worthiness for a cover; her looks are enough. The problematic influence of this particular image of Coughlin was enough for a Swimmer’s World contributor to address.

Coming to the fore here is the conflict between appearance and achievement in sport. Athletic achievement is valued more than appearance: what you do is supposed to matter more than what you look like. This equation best suits predominantly male spheres, although phrases like “fat guy touchdown” reveal how appearance still factors there. Sport is often seen to be beneficial for women because the emphasis on achievement is expected to overcome the focus on appearance, but more often than not, women face a double bind: damned if you conform to conventional female appearance, damned if you don’t. The pressure from this conflict affects all female athletes, but considering that sport goes beyond its fields of play into other arenas–from sponsorships and product endorsements to fashion spreads–appearance often wins out and disproportionately affects those with non-normative bodies: not small, not white, not cisgender, those read “in excess” of expectations.

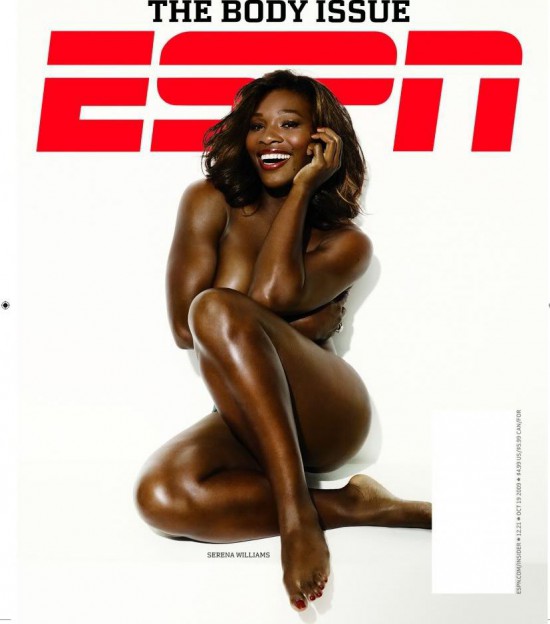

The release of the 2015 “Body Issue” coincided with debates around the bodies of two other high-achieving female athletes, Serena Williams and Caitlyn Jenner. Williams, the top-selling cover from the first “Body Issue” in 2009 (at top), was near to earning her sixth Wimbledon title when a New York Times article sparked controversy for its discussion of her body. Explicitly about size and gender but implicitly about race, the Times story is just one in a series of attacks on Williams’ body, ruminating on her larger, more muscular body primarily from the perspective of other female tennis players with smaller, white bodies. As Zeba Blay notes, the problem with the Times piece “isn’t about the fact that Williams isn’t tall, slim and a size two. It’s about the fact that she isn’t white.” Race is certainly central here, but size still matters: readings of Williams’ size and race compound and co-construct each other. Relatedly, when Corinne Gaston argues that this “type of body-shaming … comes gift-wrapped in a triad from hell: misogyny, racism and transphobia,” I would add sizeism to the list as well. Furthermore, drawing on Julia Robins’ critique, we shouldn’t allow discourse about Williams’ appearance to obscure her achievements, but neither can we easily separate her achievements from her body. The labors of her body–the acts of shaping and using it so successfully–are also part of her achievements, ones that have clearly given her a competitive advantage over the more conventionally sized/raced/gendered competitors quoted in the Times piece. This disruption of tennis’ identity hierarchies is a further victory, but one that shouldn’t continue to come at Williams’ expense.

Just four days after Williams’ Wimbledon win, Caitlyn Jenner made her first public appearance to receive the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at ESPN’s ESPY ceremony, and comparable controversies followed. As Jon Stewart noted when photos of her Vanity Fair debut first appeared, as a man we could discuss Jenner’s “athleticism, business acumen,” but now that “you’re a woman… your looks are really the only thing we care about.” Achieving femininity involves attaining an approved appearance, legitimated through cover stories like the Vanity Fair spread, but attaining that appearance often obscures other achievements. Many questioned how Jenner could merit the award simply by “putting on a dress,” showing ambivalence in the reception of her presentation: being taken seriously as a woman requires “getting work done,” arranging and engaging in the labor to approximate conventional femininity, but the challenge of that work–physical, emotional–isn’t seen as equal to Jenner’s past athletic achievements as a man. Jenner and Williams were also pitted against each other: comedian D.L. Hughley echoed others’ comments by contrasting Williams’ feminine beauty to Jenner’s and questioning why Williams would be critiqued for appearing “too masculine” while Jenner is celebrated for becoming more feminine. While this double standard should be examined, such assertions also overlook how these oppressions stem from the same problematic system. Recognizing the intersection of these oppressions strengthens their challenge to that system, and hopefully improves the opportunities for more participation and representations of non-normative women within it.