Sesame Street’s New Landlord

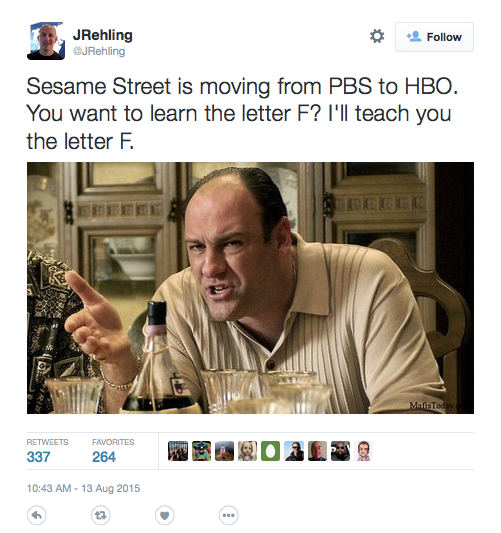

With news that HBO has negotiated a five-year deal with Sesame Workshop to broadcast Sesame Street first, and to embargo new episodes elsewhere for nine months (which would then be given free to PBS), the prospective scenarios and jokes write themselves. One envisions a new segment called You Know Nothing, John Snow. A David Milch-penned Ian McShane will now voice Oscar the Grouch, joined by his new apprentice Reek. Lena Dunham will take over Abby Cadabby’s Flying Fairy School, with comically awkward full frontal nudity from all the fairies. We’ve probably all heard that Maria is leaving Sesame Street after 44 years, but rumors have it that she does so in a gruesome “Blue Wedding” scene involving a starving Cookie Monster. Or perhaps she leaves (with Elmo, let’s hope) in a second Sudden Departure in Season 2 of The Leftovers. Today’s word is “guilt,” as introduced by special guest star Robert Durst. Bert and Ernie welcome new roommates Patrick and Frankie. Grover and Big Bird join the guys at Pied Piper. And so forth (such jokes remind me of this classic video).

But what are we to make of the deal?

But what are we to make of the deal?

Many are justifiably concerned about access for those without HBO. Sesame Street began with dreams of closing an achievement gap between middle class kids beginning school with good pre-K education, and working class kids without any such education. Thus, moving the show to the emperor of pay cable raises all sorts of concerns. See here for a smart articulation of these concerns. That said, it’s unclear as of yet how much access will be affected: if all kids can still watch later, will Sesame’s planned curriculum work at a discount nine months on? Will Sesame Workshop’s promise to produce more episodes ultimately be a net positive? Watch this space.

I’ve also heard plenty of concern being voiced about what this will do to content (see the jokes above). This concern, I believe, is unwarranted. Sure, corporate ownership affects texts, but Sesame Street isn’t a new show trying to find its feet: it’s the most successful, beloved text in American TV history. It has earned the privilege to call its own shots, and surely any deal keeps that agency alive. For what it’s worth, too, HBO doesn’t have ads, whereas PBS does (oh, okay, they’re “sponsors”), so it will actually be easier to watch Sesame Street without any ads on HBO than on PBS. HBO could undoubtedly find ways to screw the show up, but I find this highly unlikely, and if they try, surely Sesame could pack up and go elsewhere.

I’ve also heard plenty of concern being voiced about what this will do to content (see the jokes above). This concern, I believe, is unwarranted. Sure, corporate ownership affects texts, but Sesame Street isn’t a new show trying to find its feet: it’s the most successful, beloved text in American TV history. It has earned the privilege to call its own shots, and surely any deal keeps that agency alive. For what it’s worth, too, HBO doesn’t have ads, whereas PBS does (oh, okay, they’re “sponsors”), so it will actually be easier to watch Sesame Street without any ads on HBO than on PBS. HBO could undoubtedly find ways to screw the show up, but I find this highly unlikely, and if they try, surely Sesame could pack up and go elsewhere.

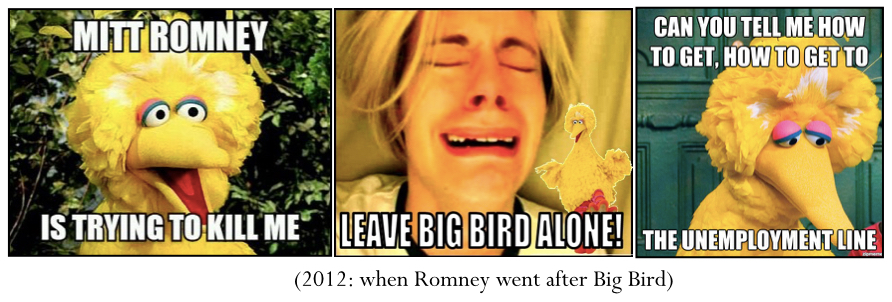

What worries me most is what this means for PBS, and for its other kids shows. Sesame Workshop and (before his death in 2003) Fred Rogers always provided PBS with its very best rhetorical defense, as evident when Mitt Romney’s 2012 suggestion that he’d cut PBS’ funding was popularly translated as Mitt stupidly wanting to “kill Big Bird” (see below). The GOP has long hated PBS, and regrets every tax dollar that goes to it instead of buying nuclear submarines. But they’ve never quite been able to break through the dam that is the public’s love and respect for Big Bird and friends. The dam is now gone. It is now oh-so-easy for a Republican Congress to say, “see, commercial television makes Sesame possible. Game over.” In such a scenario, Sesame Street lives on. But what’s downstream from the dam is everything else on PBS, especially all of its other non-tentpole children’s programming.

I want to temper that concern somewhat, though. As Laurie Ouellette’s brilliant Viewers Like You? does, we can and should criticize PBS from the left, not just from the right. PBS has regularly understood its remit to play programming that commercial television won’t play as a command instead to go even more highbrow, not to serve those consumers and citizens eschewed by advertiser-led programming. Along the way, it’s taken on ads, and often closely resembles that which it was meant to counter-program. When your most prominent non-kids show is a wet dream of British aristocracy sponsored by Viking River Cruises (whose website is currently proud of a “deal” that “only” costs $3762 per person, assuming double occupancy) and Ralph Lauren, your claim to carry the banner of the masses is laughable. PBS has long aspired to be HBO (even before there was an HBO!), so in some senses this custody agreement over Sesame Street shouldn’t seem so odd.

I want to temper that concern somewhat, though. As Laurie Ouellette’s brilliant Viewers Like You? does, we can and should criticize PBS from the left, not just from the right. PBS has regularly understood its remit to play programming that commercial television won’t play as a command instead to go even more highbrow, not to serve those consumers and citizens eschewed by advertiser-led programming. Along the way, it’s taken on ads, and often closely resembles that which it was meant to counter-program. When your most prominent non-kids show is a wet dream of British aristocracy sponsored by Viking River Cruises (whose website is currently proud of a “deal” that “only” costs $3762 per person, assuming double occupancy) and Ralph Lauren, your claim to carry the banner of the masses is laughable. PBS has long aspired to be HBO (even before there was an HBO!), so in some senses this custody agreement over Sesame Street shouldn’t seem so odd.

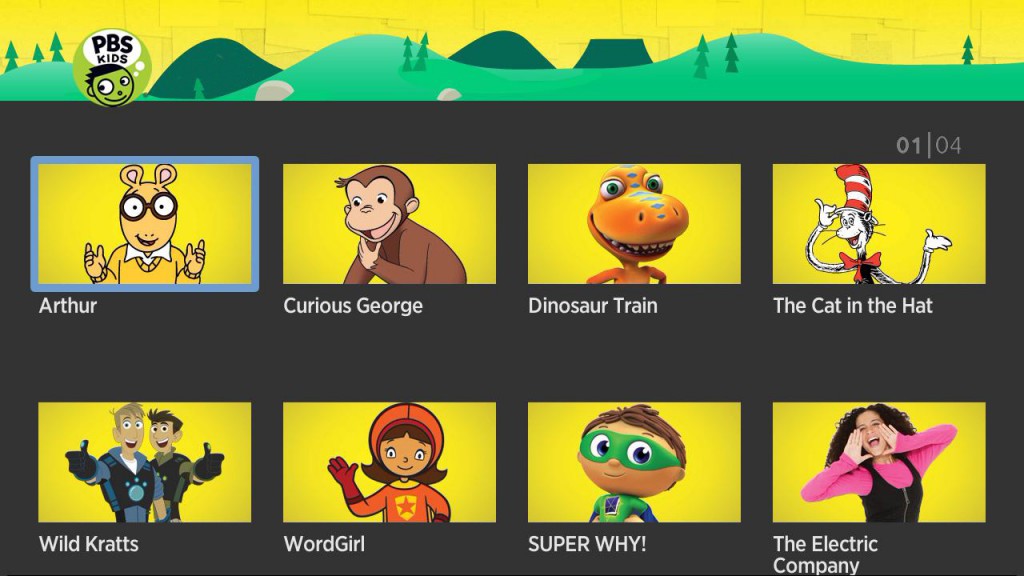

PBS’s greatest offering to American society has come from its kids programming, though, so the concern is still valid, the threat still real. Even PBS’ worst kids shows aspire to educational status. The joke that is “E/I” labeling on commercial television, wherein channels can say that anything with a happy ending is “educational” because “it teaches good morals,” is so deeply cynical, yet I’ve never found PBS cynical in this regard.

Admittedly, PBS’ educational programming isn’t the only game in town. Amazon is doing some great things, with Tumble Leaf and Annedroids, even Creative Galaxy, impressing me considerably. I was also very proud to be part of the Peabody Award jury that acknowledged Disney Junior’s Doc McStuffins for its own work. So I don’t want to overstate: even if Sesame Workshop’s deal with HBO breaks the dam, not every good, educational, important kid’s show stands to be destroyed if PBS disappears or is further commercialized. There are enough inhabitants below that dam, though, that it’s reason to worry.

It’s easy, then, to get pissed off at Sesame Workshop for this move. Personally, though, I’m inclined to say that after all they’ve done for families with televisions around the world, and after being the dam that held back the GOP’s attack on PBS for so long, it’s hard to argue that they owe us even more. They earned a right to be selfish, to think about how they – not children’s educational programming or public broadcasting writ large – will remain afloat. If there’s someone to be angry at, therefore, it’s still (1) the GOP for forcing this hand; (2) PBS for never truly being what they should’ve been in the first place, and thus for requiring Sesame Workshop and Fred Rogers to protect them from successive rounds of attacks on their funding; and (3) generations of PBS’ well-to-do “viewers like you” for demanding more British period dramas instead of realizing the channel was never meant to be there to satisfy their bourgeois needs.

It’s easy, then, to get pissed off at Sesame Workshop for this move. Personally, though, I’m inclined to say that after all they’ve done for families with televisions around the world, and after being the dam that held back the GOP’s attack on PBS for so long, it’s hard to argue that they owe us even more. They earned a right to be selfish, to think about how they – not children’s educational programming or public broadcasting writ large – will remain afloat. If there’s someone to be angry at, therefore, it’s still (1) the GOP for forcing this hand; (2) PBS for never truly being what they should’ve been in the first place, and thus for requiring Sesame Workshop and Fred Rogers to protect them from successive rounds of attacks on their funding; and (3) generations of PBS’ well-to-do “viewers like you” for demanding more British period dramas instead of realizing the channel was never meant to be there to satisfy their bourgeois needs.

A final thought on the deal, though, is about what this means for HBO. The jokes with which I began are so easy to pen because HBO’s brand identity and Sesame Street have seemed so distant from each other. HBO has put a lot of time and money into presenting themselves as the choice of discerning upper middle class adults. Indeed, a recent set of ads for HBO GO were clearly pitched at youth who thought themselves old enough for HBO’s parade of violence, sex, and profanity, and at parents hip and wise enough to realize that their kids weren’t kids any more. Thus, as much as the public discussion of this move has understandably focused on what the deal means for Sesame Street and for PBS, it’s interesting to consider this as a major shift in strategy for HBO. With the advent of HBO Now, HBO clearly has aspirations to become a premier streaming service. Netflix has its deal with Disney that will soon reap its greatest rewards; Amazon has its impressive slate of kids shows; and HBO has often had nothing remotely worthwhile for kids (Fraggle Rock ended 28 years ago). So for them to go out and buy the most famous kids show ever sends a loud message that they don’t just want to be for adults anymore. It may tell us that HBO has decided that being a streaming service heavyweight requires kids programming. Perhaps streaming services are the future and lifeblood of kid’s television; indeed, between this deal and Amazon’s interest in creating yet more high quality kids shows, clearly something is going on. But we should still worry about the coming flood that might wash away a great deal of what was PBS at its very best.

Thanks for this really excellent post, Jonathan. I was hoping someone would pick up this topic, and you’ve given some great food for thought. The points about HBO, streaming, and children’s media are particularly fascinating. The prominence of kids TV in the streaming ecosystem speaks to the target demographic (parents of young children) and the ways children consume media (on demand, frequently repeated, small bites). And of course, the persistence of a digital divide means we should all worry about the kids getting left behind during the streaming revolution.