Bollywood’s Superhero Genre: Transnational Appropriations, Labor and Referentiality

Post by Nandana Bose, University of North Carolina Wilmington

This post continues the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor, Nandana Bose, completed her PhD in the department in 2009.

Hindi cinema in the new millennium has invested considerable labor in reimagining, appropriating and indigenizing new-millennial trends, discourses and globally circulating genres such as the sci-fi/superhero genre (as well as supernatural, horror and fantasy genres). Hollywood’s decisive millennial turn towards fantasy genres, driven by the global popularity and commercial success of superhero franchises such as The Avengers (2012, 2015), Thor (2011, 2013), Iron Man (2008, 2010, 2013), Captain America (2011, 2014), The Amazing Spider-Man (2012, 2014), and Batman (2005, 2008, 2012), has been aggressively embraced by Bollywood. The surprising popularity of comic-book–based superhero TV dramas among niche Indian audiences has “led channels such as Star World Premiere HD to air shows such as Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. [2013–], The Walking Dead [2010–], and Marvel’s Agent Carter [2015–] within hours of their international telecast.”[1] In postmillennial India, digital and virtual media convergences of the Internet and the video-gaming industry, and the rapid growth and bi-directional media content outsourcing by American and Indian digital graphics and visual-effects companies have significantly impacted the generic output of the Bombay film industry. The explosion and penetration of digital media cultures have inevitably influenced the types of genres Bollywood produces. The postmillennial superhero genre is constitutively informed by digital media cultures. The digital media world informs the superhero genre in two ways. First, it is enabled by satellite/cable and Internet accessibility for postmillennial Indians who are largely urban, educated, aspirational youths, aware of global genres and the latest media trends. Second, digital media technologies such as computers, cell phones and touch-screen interfaces are textually inscribed as content as in the case of superstar Shah Rukh Khan’s 2011 sci-fi/superhero blockbuster, Ra.One, inspired by the video-game format and aesthetics.

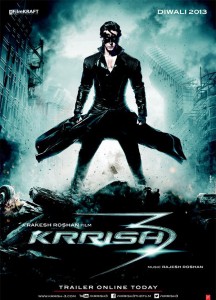

What does the superhero genre mean to contemporary Hindi cinema? What might the millennial reiterations of this emergent genre tell us about Bollywood’s industrial and spectatorial compulsions? I suggest that the emergent superhero genre of recent Hindi cinema is an incoherent textual and extra-textual simulacrum of Hollywood superhero films. The Hindi superhero genre is a highly self-conscious, referential importation of an essentially American genre that hitherto has been only superficially indigenized and localized by inserting Indian character names, (occasional) Indian locations, and the staple song-and-dance sequences. The Krrish superhero/sci-fi franchise, comprising Koi…Mil Gaya (2003), Krrish (2006), and Krrish 3 (2013), is considered Indian cinema’s first such film series. The franchise explicitly references the Rambo series (1982, 1985, 1988, 2008) in the naming of its constituent films. The blatantly imitative logic of the franchise/genre is reflected in a telling comment by its producer, Rakesh Roshan, father of star Hrithik Roshan, who plays the titular superhero: “People who have seen the film [Krrish] are of the opinion that this film is not like Hollywood, it IS Hollywood.” The physiognomy, hypermasculinity, costuming and performative style of Bollywood superheroes (Krrish and G.One), and archenemies and sidekicks (Kaal and Kaya in Krrish 3, and the eponymous Ra.One) become unintentionally parodic reiterations and appropriations of the American superhero genre, exemplifying “the imitative logic of development which situates Bombay cinema somewhere between a not-quite and a not-yet Hollywood.”[2] Perhaps this may explain the mixed reviews and reactions to Ra.One on its initial release, despite its huge budget, the star power of Khan and surrounding media hype.

Postmillennial Bollywood superhero films are citations, extensive quotations of the dominant idiom of Hollywood superhero films, gesturing towards “the creation of ‘something new with the help of references.”[3] The citational nature of Bollywood’s superhero genre reveals transnational influences in terms of the superhero star body and hypermasculinity; and the creative talent, visualization and industrial labor involved in costuming and special effects. Since his debut in 2000, the superstar/hero Hrithik Roshan has sculpted a “pumped-up” physique through intensive sessions at the gym, adopting western bodybuilding practices such as DTP or Dramatic Transformation Principle. Inspired by Hollywood’s legendary macho men, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone and Jean-Claude Van Damme, he transformed himself from a lanky “boy next door” to an icon of hypermasculinity befitting superhero roles. As the eponymous Krrish, Bollywood’s first fully realized Superman-style hero, Roshan displays a muscular yet lithe body in action sequences and performs gravity-defying, daredevil stunts without body doubles. An August 2012 Men’s Health cover feature provides a meticulous account of Roshan’s gruelling exercise and dietary regimen in preparation for his superhero role in Krrish 3 under the guidance of famed American trainer Chris Gethin, who was hired for an astronomical sum.

Imitative of the caped crusader and modeled on Hollywood superhero costumes and accoutrements (face mask, underwear and so forth), Krrish dons a skin-tight, superhero outfit that accentuates his physique and emphasizes the hero’s idealized hypermasculinity. Following in the tradition of overly sexualized Hollywood superwomen in skin-tight costumes, and inspired by Batman, one of Krrish’s archenemies in Krrish 3, a mutant named Kaya, is clad in such a svelte, clingy outfit, made of rubber and latex, that the star playing the role, Kangana Ranuat, complained that she felt naked in it. Meanwhile, the much-publicized blue-latex costume worn by Khan as protagonist G.One in Ra.One, reportedly costing a million dollars, was designed by Robert Kurtzman and Tim Flattery, and created by a team of specialists in Los Angeles.

Besides the transnational labor, talent and visualization involved in costuming, Hollywood special-effects teams have collaborated with Indian graphics companies (such as Prasad EFX) to upgrade the quality of visual effects in the Krrish franchise. Aided by Hollywood’s Marc Kolbe and Craig Mumma, who had both previously worked on such films as Independence Day (1996), Godzilla (1998) and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) as well as the prequel to Krrish, the E.T. (1982)–inspired Koi…Mil Gaya, Krrish set new standards in Indian film CGI. According to Mumma, “Krrish is indicative of Indian cinema’s ascent to the global arena. It will be a trendsetter because it is among the first few films to leverage global expertise and technology to make the film larger than life.” Thus, the local/global imaginative, creative and technological collaborations that engender the Bollywood postmillennial superhero film reveal “an international division of cultural labor that supports the invigoration of new markets and commodity forms.”[4] Transmedia extensions of Krrish as comic book (Krrish: Menace of the Monkey Men), video games (Krrish: The Game and Krrish 3), and animated television series (Kid Krrish aired on Cartoon Network India, and J Bole Toh Jadoo on Nickelodeon) predictably emulate the Hollywood model of transmedia reiterations of the superhero. The Bollywood superhero genre’s extra-textual mimicry of the pre-release marketing, merchandising, branding and transmedia franchising of Hollywood superhero blockbusters also deserves closer scrutiny.

Notes

[1] Sharmila Ganesan, “Spandex on the Small Screen,” Sunday Times of India, July 5, 2015, p. 13.

[2] Nitin Govil, Reorienting Hollywood: A Century of Film Culture Between Los Angeles and Bombay (New York: NYU Press, 2015), p. 45.

[3] Ibid., p. 69.

[4] Ibid., p. 72.

Indian cinema is now producing more superhero movies but the good thing is that they have not forgotten the a typical Indian viewers expectation from the film. This is the reason these films are doing good in India as well as in rest of the world.