“Not Linear or On-Demand”: Television in “the Internet Age”

Post by Catherine Johnson, University of Nottingham

This post continues the ongoing “From Nottingham and Beyond” series, with contributions from faculty and alumni of the University of Nottingham’s Department of Culture, Film and Media. This week’s contributor is Catherine Johnson, Associate Professor of Film and Television Studies in our department.

In March 2015, Tony Hall (Director General of the BBC) outlined his vision for the BBC as it entered “the internet age.” Hall argued that while broadcasting had been responding to digitization for the past twenty years, until recently it had been relatively unaffected by the internet. This, Hall claimed, was changing as broadcasters responded to a new landscape in which television and the internet became more entwined.

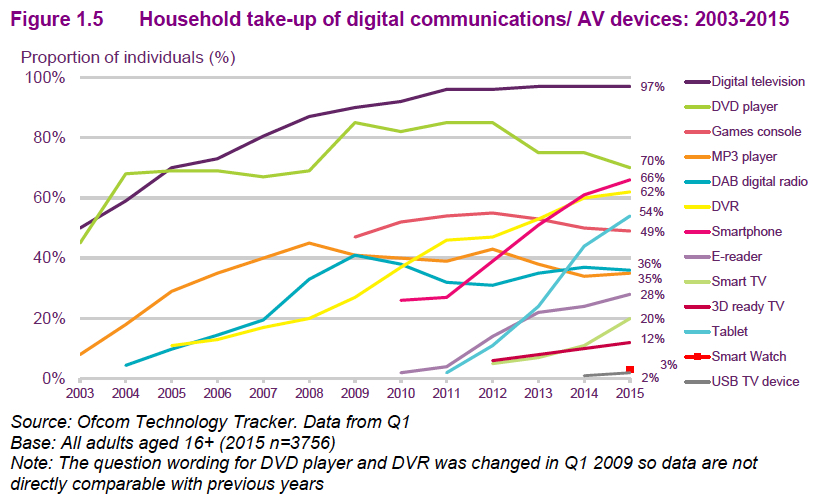

Ofcom’s annual Communication Market Report (CMR) offers a useful overview of the changing media landscape in this “internet age.” At the end of 2014, 56% of UK households had a TV connected to the internet, either via a set-top box or smart TV, and 83% of UK premises were able to receive superfast broadband. 54% of households owned a tablet (up 10 percentage points from 2013), smartphones were the most widely-owned internet-enabled device (present in two-thirds of UK households), and 4G mobile subscriptions increased from 3% at the end of 2013 to 28% at the end of 2014.

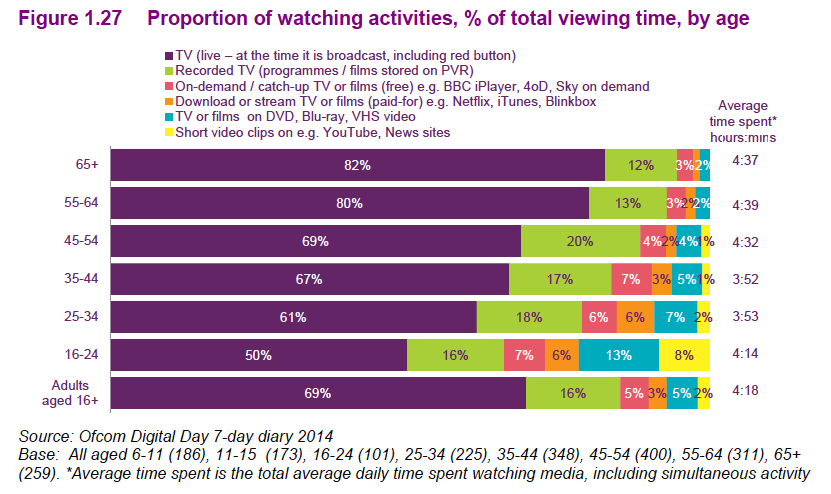

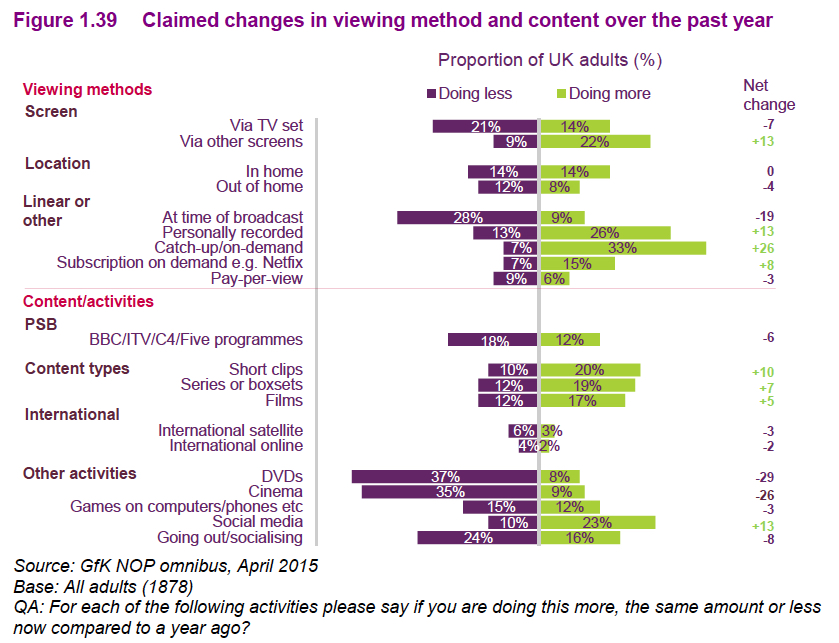

Amid increasing access to internet-connected devices, broadcast TV viewing remained robust, with traditional live television accounting for just under 70% of the total time adults spent watching audio-visual content in the UK. However, this did represent a decline of 12 minutes annually from the previous year. Data from the UK ratings company BARB suggested that about half of this decline could be accounted for by viewing on catch-up, video-on-demand (VOD) and subscription services (such as Netflix).

Certainly, non-traditional viewing has risen over the past year. Viewing of non-subscription catch-up services (such as BBC iPlayer) has increased by 26% and 16% of UK households now subscribe to Netflix. Meanwhile, smartphones, tablets and 4G are driving consumption of television content on alternative internet-enabled platforms, particularly among younger audiences, with 16-24s more likely to use a computer or smartphone than a set-top box to access VOD TV services, and with 50% of 4G users accessing audio-visual content on their mobile phones.

This is a complex landscape, with the changes in behavior and access to technology varying by age groups, location and economic status. What this landscape points to, however, is an increased interconnectivity between television and the internet. While this fast-moving environment raises significant difficulties for the regulation of public-service television, it also presents challenges to broadcasters attempting to navigate a landscape in which television is increasingly distributed and accessed online, whether through internet-connected set-top boxes and smart TVs or through online services available through PCs, laptops, tablets and smartphones.

All of the UK’s broadcasters have an online web presence, typically in the form of a website and VOD service. These VOD services are available across a range of devices, including PCs and laptops, tablets, smartphones, games consoles, set-top boxes and connected television sets. In October 2015, the launch of Freeview Play made all of the public-service VOD services (alongside a suite of digital television channels) available on a television set without subscription, through the purchase of a Freeview Play enabled smart TV or set-top box. The UK’s pay-TV providers also offer their own VOD players as part of their subscription packages, and viewers can access standalone VOD services through individual subscription or download programs on a pay-per-view basis.

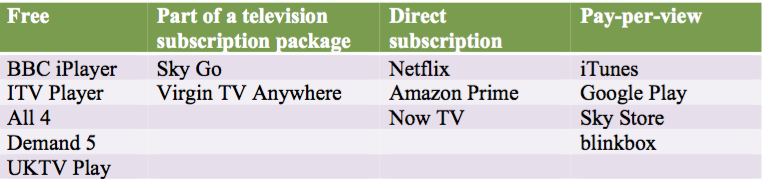

Table 1: Top online VOD services listed in Ofcom’s 2014 Communications Market Report, based on claimed use of selected online VOD services in the UK for 2013-14.

There is a tendency within reports such as Ofcom’s CMR to distinguish between broadcaster VOD services, such as BBC iPlayer, and new OTT providers, such as Netflix, with the former understood as “catch-up” services and the latter as subscription services used to access content not available on other platforms. Yet this positioning of broadcaster VOD services as “catch-up” fails to account for the ways in which they blend different modes of viewing in an attempt to appeal to the different “need states” of television viewing. It is important to recognize that broadcaster VOD services provide not only a mechanism to catch up on broadcast programs that have been missed, but also act as a site for accessing and viewing live and original programming. The UK’s free-to-air commercial public-service broadcaster, ITV, noted in 2014 that over 25% of all requests to its VOD service ITV Player were to watch live TV, and the interface now includes a “Live TV” button among its permanent tabs. In this case, the distinction often made between linear and non-linear television breaks down as viewers use non-linear on-demand services to access linear broadcasting.

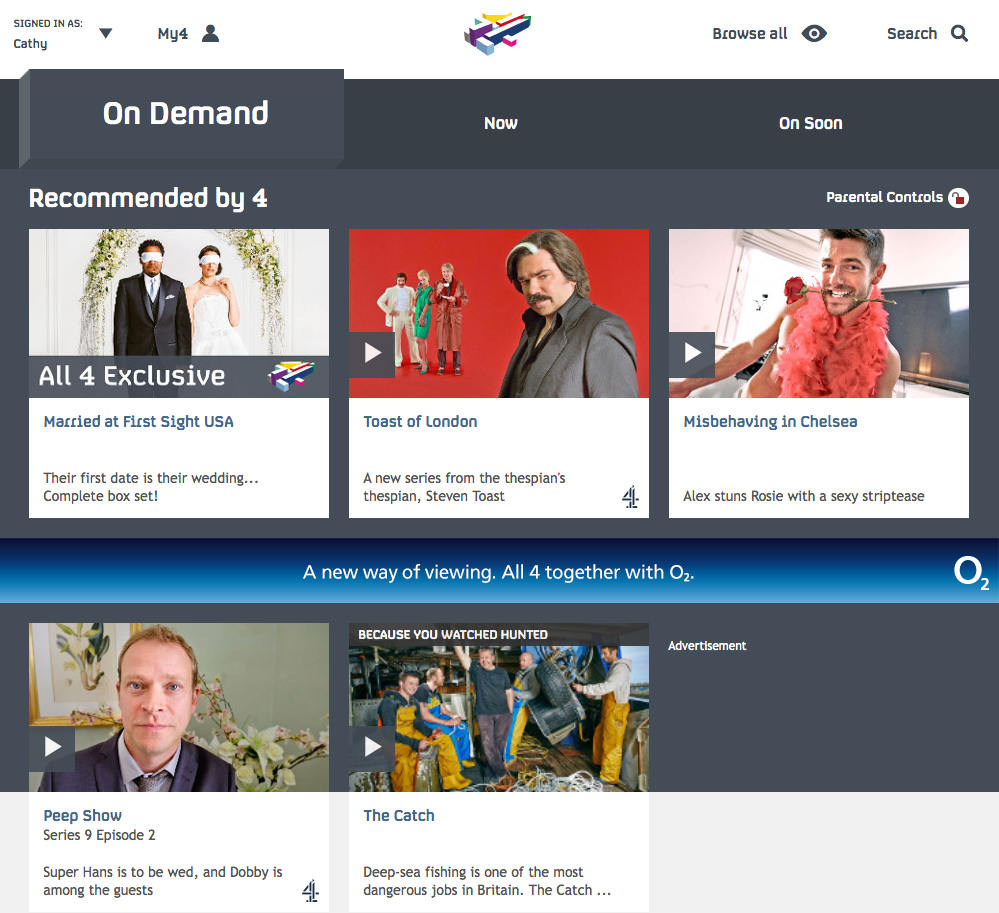

A year later in 2015, the UK’s other main commercial public-service broadcaster, Channel 4, re-launched its VOD player (4oD) as All 4, positioning it as its seventh “channel” and a central hub of its activities and identity as a broadcaster. All 4 replaced Channel 4’s broadcaster website as well as 4oD, effectively positioning the broadcaster online as a VOD service. Tim Bleasdale, Creative Director of the digital product design company Ostmodern, vividly described his company’s work on All 4 as creating “a world where 4oD has eaten the rest of Channel4.com.”

The design of the All 4 online interface itself is based on offering viewers three differentiated experiences. “On Demand” is the tab through which to access catch-up and archived programs, including box sets. “Now” is the place to watch live broadcasts, interactive formats, clips, new shorts and social-media conversations. “On Soon” showcases exclusive online premieres, promos and trailers, as well as being the place to set reminders and alerts. Far from being a catch-up service, All 4 attempts to collapse the boundaries between broadcasting and VOD. As Laura Slattery of The Irish Times argues, All 4 can be understood as the presentation of “all of Channel 4’s linear channels (Channel 4, E4, More 4), its catch-up content and its digital exclusives in one place – reflecting the fact that younger viewers increasingly do not differentiate between live television and video-on-demand.” Jonathan Holmes concurs, claiming that All 4 represented “yet another sign that broadcasters no longer view online as an adjunct to their main mission, but as central to modern television.”

More controversially, in 2014 the BBC revealed its proposal to transform its digital channel BBC Three into an online-only service delivered through its VOD service BBC iPlayer. While this decision was driven significantly by the need to cut costs in a difficult political environment (as Liz Evans discussed in an earlier Antenna blog), it was also positioned by the broadcaster as a means of responding to changing viewing habits, particularly of younger audiences. Echoing much of the rhetoric around the launch of All 4, Damian Kavanagh (Controller, BBC Three) described the move as merging what is great about broadcast and digital in order to “give something of the digital world, not just in it.” Although the service has not yet launched, the BBC’s proposals for BBC Three online again focused around need states with the service positioned around two pillars: “Make Me Think” and “Make Me Laugh.”

As with All 4, Damien Kavanagh has described this as an opportunity to combine the delivery of traditional television programming with different forms of content, from short-form to image-led storytelling and increased interaction from viewers. However, while the channel would have a dedicated home online, the BBC claimed in its proposals that the different kinds of content would sit within different sites online, with short-form and digital content emerging on social platforms such as Tumblr, YouTube, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, and long-form content appearing on iPlayer, as well as on broadcast channels BBC One and BBC Two. This model points to the difficulties of blending online and broadcast. Although VOD services such as All 4 and BBC iPlayer can act as hubs for television content online, the BBC’s proposals suggest that there remains a distinction between digital-only content (described by Kavanagh as short-form and digital) and broadcast content (understood as long-form programming). Within the BBC’s thinking, VOD services such as the iPlayer seem to emerge as extensions of broadcast channels (a place to access long-form programs online), rather than as a site that can accommodate other forms of “digital-only” content that might be better suited to social platforms such as Tumblr or Twitter.

While I am usually resistant to predicting the future, what is emerging is a television landscape in which VOD services sit alongside channels on our television sets and in which live broadcast programming is offered within the same online interface as on-demand and interactive content. This integration of online and broadcasting is unlikely to lead to the decline of live, linear television viewing, but it does change the relationship between broadcasting and on-demand. Indeed, when announcing the launch of All 4 David Abraham, Chief Executive of Channel 4, claimed that the future of TV lies “not with either linear or on-demand, but a creative and visual integration of the two worlds, blending the strengths of both into a single brand.” To understand television in the internet age, we need to recognize that far from being separate or distinct, linear and non-linear television are entwined in a media landscape in which broadcasting and online are, and will be, increasingly interdependent.

Thanks for such a detailed look Catherine–it is difficult to make sense of these distinctions in one’s home context–this is really helpful for understanding the state in Britain. How deep are the series offerings on the free services? In the US, it is typically only the five most recent episodes, which prevents a full season binge that can be done with a service like Netflix. A struggle is emerging here because the VOD services want full seasons, but Netflix (and other secondary buyers) are now paying less for series that have had such extensive VOD exposure leading the studio/networks to be hesitant to offer full seasons–any similar issues in the UK?

An interesting and detailed overview of the UK landscape. However, one of the things that does stand out is still the number of people who do watch live. 69% of content is watched live (and is VOD watched live ‘live’?), and the amount of recording has fallen. However, that might not be to do with people watching more VOD, but simply that since digital switchover in the UK, a large amount of (analogue) VCR’s stopped working, and many people (judging by my customers) have not got around to replacing them yet, even 3-4 years later. They simply got out of the habit.

Many people (and this is not just older people) barely use the smart features on their new TV’s, and even if they do, its often no more than Iplayer. Often slow broadband speed and the ‘habit’ of watching VOD on a laptop etc means they are not making full use of what they have.

However, many people watch everything on demand or pre-recorded, although even though will watch ‘water cooler’ moments live. And its true that Netflix, Amazon prime etc are becoming far established. But looking at the 16-24 age range, the really big change is the amount of free conetn they are watching, such as Youtube. It will be interesting to see if they carry on watching that sort of content when they are 34, and have two young children! Will they revert to the mean?

I suspect that human nature takes a lot longer to adapt than the technological possibilities allow. One of the problems with seeing the TV landscape through the eyes of commentators is they tend not to be representative. They tend to have fast broadband, the latest tech, above average income, and more extensive services available than much of the population. They are also much more likely to have seen ‘Orange is the New Black’ than Eastenders or Bargain Hunt.

VOD is here to stay, and its going to grow far more. But its not the whole story, and in fact is a relatively small part of the whole at the moment. It will be interesting to see how 4K changes things, because at present, its basically VOD or nothing for 4K!

Amanda – looking at Iplayer, C5 and C4, most programmes might be on for an episode or two. Some will have a whole series, but UK series tend to be much shorter than US ones anyway. C4 has boxset style offerings for things like Father Ted, but newer stuff will be for a week or two, not everything. BBC Iplayer has a huge range of stuff, and might be a whole 6 episodes of an Attenborough, etc.