The Force Re-Awakens: Star Wars, Repetition, and Nostalgia, Part 1

Since the release of J. J. Abrams’ The Force Awakens, the Internet has been alive with complaints about it as an exercise in nostalgia that revels in mere repetition, pastiche, photocopying, etc. (I’d cite some examples, but at this point it’d be like citing examples of cats being popular on the Internet: you can find these complaints anywhere). Sometimes, these ooze with contempt for fandom, writing the movie off as “fan service” or “fan fiction,” as if that’s the worst thing anything could ever be. Some such posts and reviews rehash the tired, ancient, and utterly insipid suggestion that anyone who enjoys a blockbuster Hollywood franchise film is a brainless sheep, grazing here in the pasture of Farmer Walt. Others are less unkind to the audience, but instead regard themselves as offering aesthetic critiques, arguing that there is “nothing new” and wringing their hands about a culture of repetition.

I want to respond to and engage with this line of attack. I don’t intend this as a defense per se – since the film obviously has many lovers whose gushing praise of the film is as prevalent as the attack, and since I think the film is going to be just fine (understatement alert). Nor is this a plea for critics to come around and see the light, since they’re welcome to dislike the film. Rather, it’s interesting to stop and think through what’s being said about originality, nostalgia, franchising, and repetition.

In this post, I’ll discuss what is in fact new, then in a follow-up post I’ll ask “so what if there’s repetition?” and explore the bizarre criticism that The Force Awakens looking and feeling like A New Hope is contemptible. To discuss what’s new in the film requires getting into its guts, so this post will focus heavily on the plot and characters, whereas the next one will examine broader issues separated from that plot and those characters, of repetition, sequels, and originality.

A warning – spoilers abound. Don’t read past here if you don’t want to be spoiled (but also, hey, it’s been out for three weeks now. If you don’t want to be spoiled, go see it already).

To begin, let’s acknowledge that the film does indeed engage in quite a lot of repetition with variation. The (1) First Order is catching up with (2) Poe, who is believed to have important information regarding the whereabouts of a lynchpin of the (3) Resistance efforts against it, when (4) BB-8 is set loose on the desert planet of (5) Jakku with said information. Our young desert-dwelling hero with a mysterious past, (6) Rey, stumbles into an alliance with (7) Finn, and the old warrior (8) Han Solo, while that pesky evil organization engages its mega weapon, (9) the Starkiller Base, to destroy (10) many planets, to show its supreme fascist power. Positioned within the evil organization, and following the leadership of (11) Snoke, and alongside numerous Brits in grey uniforms, is the disliked Sith figure of power and malevolence, (12) Kylo Ren, who has a fondness for helmets and dark clothing. After encountering numerous interesting species, some friendly some dangerous, our heroes find plans to destroy this nasty base, team up with the x-wings to do so, and in a race of time to see who will strike first, the good guys or the bad guys, yay, the good guys win and destroy the base, but not before the nasty Sith faces off with an old frenemy and kills him, much to the horror of our onlooking heroes. Replace those numbers with, respectively, the Empire, Leia, the Rebellion, R2-D2, Tatooine, Luke, Han, Obi-Wan, the Death Star, Alderaan, Grand Moff Tarkin, and Darth Vader, and you have the plot of A New Hope. So, yes, there is definite overlap.

What’s new?

A lot of scenes, while ostensibly similar, carry vastly different weight precisely because they’re happening in the seventh movie of a franchise that is now 38 years old. Saying that a scene is “the same” as one in A New Hope is like saying a 60s style diner is “the same” as a diner one would actually have visited in the 60s, when of course it’s not – time has intervened and history has added and edited meaning. Maybe that diner you used to eat in as a kid looks just the same, but its neighborhood has changed, the owner has wrinkles, the people sitting there are no longer choosing between it and twenty other similar diners but between it and a Thai place, Chinese takeout, arepas from a food cart, and so on, the restaurant has its own stories, and thus you’re simply wrong if you think you’re reacting to it the same way as you used to. When context changes, meaning changes, and this script would surely have been written with an awareness of context changing. Add “small” changes, since this is not repetition – it’s repetition with variation – and add history, and a great deal changes.

The Force Awakens situates us in a galaxy where fascism and evil seem doomed to return, to hold the day, as a constant threat, even when we thought it was vanquished. By comparison, Leia’s Rebellion in A New Hope has been fighting the Empire for how long? Star Wars fans can now answer that question precisely, but when the film came out, we didn’t know whether it was a recent threat or a long-running one. This changes the stakes considerably, and proposes a bleaker, darker world, one that is further signaled by relationship failures and by loss – Han and Leia didn’t live happily ever after, they lost their son, Leia lost her brother, we all lose Han (and where, really, is the parallel there? The worst unplanned death of a good guy in the original trilogy is who? Porkins? Random Ewok #8? Han’s tauntaun?), and Rey feels the absence of her parents as Luke never did. Tears are shed. The kids with whom I watched The Force Awakens the second time found the movie a downer, and many adults did too, whereas A New Hope is effervescently upbeat.

Our bad guy is different too. When we encountered Vader, he was something of a solitary figure, derided for practicing an obscure religion, and simply A Bad Guy; by contrast, Kylo Ren not only follows Snoke, a Sith Lord, in a way that automatically privileges him over his fascist ginger (am I the only one to see a South Park reference here?) counterpart, and that puts him in a long line of Sith, but we know at this point in the franchise to assume that bad guys have good struggling within them, so we’re asked to relate to him differently. Vader, moreover, is confident and assured: he doesn’t run anywhere, he just strides; he never questions himself (till Return of the Jedi); he seems certain of victory. Kylo Ren, though, is replete with weakness, sensed by Rey when she backwashes his mind-reading trick; he rages like an angry toddler; he shows off; and for half the film he has his mask off, making him more human than Vader. Defeating him therefore seems to require a wholly different bag of tricks than defeating A New Hope’s Vader.

Or take the much-discussed killing of Han, reminiscent of the killing of Obi-Wan. When Obi-Wan’s killed, he’s had about fifteen minutes of screen-time, if that. By contrast, when Han’s killed, he’s arguably the most beloved character in a 38 year-old franchise, somebody who many audience members may’ve imagined they were on the playground, may’ve (should’ve?) even had crushes on. And since it’s Harrison Ford, he’s also Indiana Jones. Comparing the emotional impact of their deaths is thus plain silly. Let’s remember, too, that Obi-Wan wanted to be struck down – his little smirk before he stops fighting is one of the best parts of A New Hope, as is his mercurial threat that striking him down will only make him stronger, and the suggestion that Luke’s meant to watch, that Obi-Wan’s death is a sacrifice in aid of some future gain. Barring major new information, though, Han’s just dead: he won’t be appearing in ghost-form in a swamp near you anytime soon. He doesn’t do it to help Rey along a path. Obi-Wan doesn’t appeal to Anakin as his old friend, as Han appeals to his son; Obi-Wan is sure either than Anakin is gone or that he can’t bring him back except through death, whereas Han wants to bring his son home and thinks for a minute that his appeal is working.

Importantly, too, A New Hope is governed by young people, and brims with youthful desires to become someone, to grow up, to create something new, and to throw off the shackles of old guardians. Uncle Owen is unlikable for holding Luke back (as is Grand Moff Tarkin for holding Vader in check, for that matter), and Obi-Wan is exceptional precisely because he plays the role of cool uncle saying that Luke should go ahead and train as a Jedi, travel the galaxy, leave home. There’s more than a touch of the sixties in these folk. The Force Awakens, by contrast, respects and reveres its elders. Only Kylo Ren rages against his parents, and we as an audience are presumed to side with those parents. The film is quite tender in its brief treatment of Leia and Han as an old couple, Mark Hamill’s face in the closing scene is worn down by time, even new character Maz has a wisdom to be heard. Ironically, in other words, when critics say The Force Awakens is drenched in nostalgia, they’re noting that it’s operating in a very different mode from the future-centered New Hope.

And then there’s Finn, Rey, and (the admittedly under-developed) Poe. I can’t help but notice that an overwhelming amount of the attacks on The Force Awakens offering “nothing new” are from white guys, who clearly don’t get why it might matter that the franchise – the most successful franchise in media and merchandising history, no less – has just been entrusted to a Black English man, a White English woman, and a Guatemalan-American man. This is massive for identity politics. Perhaps not unique, but big. Especially for a franchise that has often relegated people of color to being comic fodder or the basis for stereotyped alien races. As a kid playing Star Wars, I was invited to play a host of white mostly-American figures (or the Black Bad Guy), but if kids are playing Star Wars now, they’re presented with a much wider range of options.

Finn appears in my plot parallel exercise above as a counterpart to Han, but is not at all Han. He’s a defector – a role entirely new to the films – not a rogue. Being a defector invites us to think about the ethical positioning of being part of the First Order, in a way that none of the original movies ever cared about, and in a way that immediately positions him as principled, whereas Han’s principles are notoriously questioned throughout A New Hope. Finn’s not as sure of himself as is Han, and he’s arguably allowed a wider range – brave, crack shot, scared, tentative, funny, impulsive, controlled, along for the ride, ready to act.

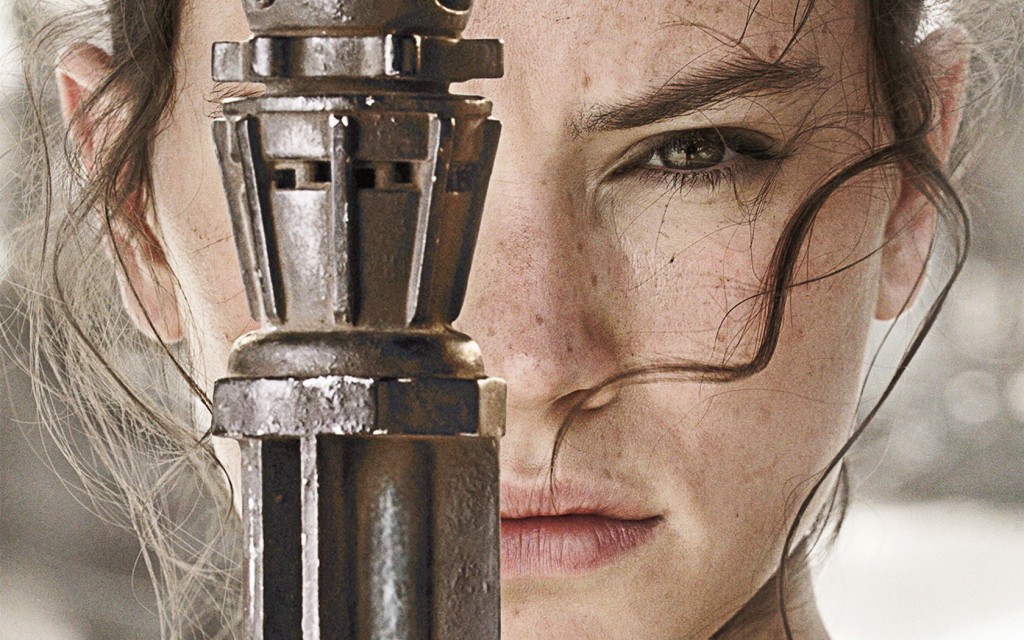

Rey, meanwhile, is the movie’s centerpiece. There are some nominal similarities to Luke, but she’s so much more capable, less whiny. The schtick surrounding her annoyance at Finn taking her hand tells us a lot about her independence. The Force is stronger in her, as is having her shit together. And let’s be honest that Daisy Ridley runs circles around Mark Hamill’s rather poor acting from A New Hope. Her Rey is the first bona fide hero in the filmic franchise: I count Han and Obi-Wan as sidekicks, Luke was too dithery and needed two films to get up to speed, and Episodes I-III’s Anakin was so horribly acted that he just existed as a long, stale filmic fart. Despite being the film’s clear hero, she doesn’t destroy the Starkiller Base, nor does she defeat the bad guy, and yet she offers a stronger spine for the next two films than Luke ever did.

I could go on about all sorts of little changes, too, but each of the above changes tone, theme, and stakes.

The Force Awakens isn’t just A New Hope in slightly newer clothing, therefore. But in the next post, I’ll allow the critics the day, assume it is or that my comments above aren’t convincing, and I’ll then ask, “so what?” Why are people bothered that Film #7 in a series seems a lot like some of the earlier films? And what might they be overlooking about how storytelling in this mode works?

[…] claim is fairly easy to debunk. Media scholar Jonathan Gray does so in fine fashion here. In this post, I’d like to throw my support behind Gray’s position, by showing that The Force […]

Great and a fun read. Only things I’d take issue with…

Not sure if it’s your intent, but you seem to downplay Luke’s character development in the originals. I think the fact that Rey is so strong and independent is definitely new and fresh, and that’s cool, but I also think the fact that it took luke three films to mature is not a bad thing… You get to watch him make leaps and bounds in his development as a Jedi from movie to movie, something that might not be as apparent or meaningful wit Rey, who is a badass from the get go. So I just wouldn’t phrase it as “it took him two films to get up to speed.”

Also, I feel like obiwan had way more than fifteen minutes f screen time in new hope… I could be wrong there, and I agree that his death doesn’t compare to solos, but I’d bet that viewers of the a new hope we’re pretty sad to see him go watching in theaters (and also I you’re gonna bring Harrison fords role as Indy into the discussion, you could make arguments for alec Guinness being a beloved actor with many important previous roles).

But yeah, dank article

[…] with the film as you watch, that’s not a plothole: that’s your own dumb ass. Also, this essay about the film being a repetition with variation (I’d call it “theme and […]