Media Studies, Have We Lost Our Feminism?

At Console-ing Passions this April, Tara McPherson exhorted the plenary audience of mostly female scholars to not shy away from studying digital media technology and questioned whether feminist scholarship is falling to the wayside, particularly in textual analysis-based work. While I don’t feel we can rank media studies subdisciplines in relation to potential for feminist scholarship, her talk provoked me productively. I came away with ongoing questions regarding why feminism seems lost at times in contemporary media scholarship and the place of feminism in my own work and life.

At Console-ing Passions this April, Tara McPherson exhorted the plenary audience of mostly female scholars to not shy away from studying digital media technology and questioned whether feminist scholarship is falling to the wayside, particularly in textual analysis-based work. While I don’t feel we can rank media studies subdisciplines in relation to potential for feminist scholarship, her talk provoked me productively. I came away with ongoing questions regarding why feminism seems lost at times in contemporary media scholarship and the place of feminism in my own work and life.

The second question is easier to tackle than the first, so I’ll start there. In the tradition of feminist standpoint theory, I/we need to remember as scholars and teachers that despite how we may professionalize and depersonalize our writing, that our questions and approaches are shaped by who we are and where we’ve been. So, to illuminate where I write from, I grew up the daughter of a Mexican mother and German and English American father, in mostly white neighborhoods in the U.S. I thus write as a Latina and Chicana, with these identities claimed mostly as an adult, and as mixed race. My mother didn’t get the opportunity to go to high school, and my parents, while they helped me get a college education, never expected me to pursue graduate degrees. Especially important to my work today, I later became a social worker, and worked for several years with low-income families and Latina and African American teen parents in San Francisco before returning to graduate school to pursue a Ph.D in media studies. Do my mixed ethnic background, class positioning, past romantic partnerships with women, work experience, or even my feminist values make my scholarship more feminist, however?

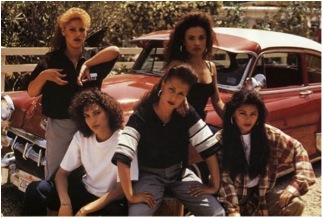

There’s a story I tell sometimes when asked what inspired me to become a media studies scholar. One of my days working with teen parents has stuck with me; it was a screening of Mi Vida Loca, Allison Anders’ film about Latina gang members. The girls were riveted, and later told me that it was the first time they’d seen themselves in a film. (Which is not to say that I’m proposing Latinas should always be portrayed as cholas or as working class, but that we all want to see ourselves represented, respectfully, in the media). In my visits to my clients’ homes I also saw how many of them were very isolated, with only their babies and a television to keep them company. As I considered what mid-1990s television offered them in terms of role models or inspiration to even finish high school, I realized just how much media representation – or lack thereof – matters. This is part of what is feminist in my work; I’m motivated by the fact that these young women are not there, on the TV or movie screen, or behind the scenes telling their stories. But Console-ing Passions made me think about how I might better foreground feminism in my research, teaching, and mentoring. We may assume it’s “built in” to our work, as a colleague and I joked at the conference, but our readers and students don’t necessarily know that.

Excellent anthologies such as Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra’s Interrogating Post-feminism and the work of a number of smart scholars, many who contribute to Antenna, aside, the word feminism is coming to feel out of place in contemporary media scholarship. As we’ve become more integrated into the academy, it seems we’re in fact expected to build in feminist, anti-racist, and related objectives but not focus on them too directly. We’re also not always studying histories of oppression that contribute to the dearth of female and non-white voices in media production or the impact of media texts on audiences, which at worst, I think, can result in analyses that are far removed from how media matters. We might be viewed as less than rigorous scholars if we call attention to or take an activist stance when we encounter denigrating representations, cite Gloria Anzaldúa or bell hooks before Foucault or Stuart Hall, or acknowledge that we personally are motivated by feminism and related ideals. And I write this as someone with the new freedom of tenure, remembering that it often is less safe to be open on these topics as a graduate student or untenured faculty member.

I don’t think all media studies scholarship should be feminist or social change-oriented, but I do think we play a role in creating space for this work, and that what we say and what we leave out has an impact. I’d love to hear others’ thoughts on this as well. What’s your opinion on the integration of feminism in contemporary media scholarship? How can scholars successfully accomplish this? And do these issues resonate in the same way for younger scholars?

Thanks for this, Mary. While I know you are right that feminism seems less central to media scholarship than it once perhaps was, I find this an unendingly perplexing situation. Feminism specifically–and critical perspectives more generally–are wholly foundational to my conception of what media studies (from a cultural studies perspective) IS. Yet I think that this may be less and less the case as media studies (and TV studies in particular) becomes more established within the academy and as television itself becomes more culturally legitimated. I’m loathe to say this, but I was troubled by the lack of explicitly feminist and critical perspectives in some of the Console-ing Passions papers I heard. Is it that more secure institutional positioning seems to lessen the need for such an oppositional stance? Are graduate students not being taught that television studies is, or should be, feminist? How much does this have to do with the ways that “feminism” itself can be made to seem an outdated word in a culture overrun with postfeminist “common sense”? More questions than answers, perhaps, but I much appreciate you opening up the conversation.

Dear Mary, I was delighted to read your message, because I too, having been a feminist in the “second wave” 1970s, feel that our message is once again getting lost. Remember REAL women in the 1980s that gave the “F-word” a really negative connotation??? In spite of this, you can look me up on the web, where many of my artices can be found. Have just written a new piece about the history of feminism between the 1980s and into 2008,where I comment that we not only need to continue to MENTOR students, but also reiterate that feminist work provides new insights about both male and female behavior. Furthermore, we should in our research 1. pay explicit attention to the inequitable power dimensions of gender relations in all human situations; put women at the center of our research; 3. integrate gender with other spects of identity, such as race, class, etc.4.be action oriented as to how to improve women’s status; and 5. include the subjects of the research in question- and data construction. You may also be interested in my latest book: Gertrude J. Robinson (2005) Gender, Journalism and Equity: Canadian, U.S. and European Experiences. Cresskill: Hampton Press.

Thank you, for these valuable comments and to Gertrude, for your suggestions to scholars regarding keep gender central to our research. I look forward to learning more from your book. Much appreciated!

Thank you for this thought provoking post Mary. I was inspired by Console-ing Passions and Tara’s talk too, especially for how the conference reminded me that the feminism in my scholarship (game studies) still has a place, and a place where I can keep the volume of my feminism turned up. In my paper for CP (What is feminist game studies?), I started to outline how and where feminist perspectives can be integrated into game studies, but also how feminist scholarship should shape the relatively new field, not just respond to it. I was motivated to write this paper because I too have noticed the tendency in contemporary media studies to turn down to volume on feminism. I think this reflects in academia the same post-feminism climate interrogated in Tasker & Negra’s book. The ethos seems to be, you will be called out for NOT acknowledging gender/race/class/sexuality aspects of your object of study (once women shat on the table of cultural studies in the 70s, to reference Hall, we can’t go back), but this is often simply a gesture, a footnote, to those concerns with very little sustained or integrated critique. When sustained attention is present, the work is marginalized – into a gender (read women) panel or a special issue on race. What happened to the lessons of hooks, Anzaldua, Foucault, etc., who demonstrated the impossibility of examining culture and power without doing intersectional, interdisciplinary work? Tara’s reminded us of that, with her oft-tweeted reference to silo-breaking.

I also think the diminished presence of feminist work is related to new terms in the field that were being defined with little to no gender critique, such as “quality TV”, “casual vs. hardcore games”, “fandom.” Thankfully each of these terms and others are finally being contested and discussed with attention to gender/race/class/sexuality. In regards to standpoint theory, I’ve been increasingly perplexed by and annoyed at the renewed interest in textual analysis (close readings of LOST, MadMen, whatever) that rarely acknowledges the subjectivity of the reader and how her/his analysis and interest in THAT PARTICULAR TEXT is influenced by her/his personal history.

I am thrilled by the conversation you have provoked here because it turns the volume of feminism up ab it, and I welcome the sound of it.

Thanks, for these thoughtful comments. I wonder also if the establishment of gender studies and ethnic studies departments on college campuses, while absolutely important, in part has resulted in a fragmentation of intersectional work and drawn us into too many camps to continue having joint discussions…

Again, not a critique of the departments, but of the need to encourage and nurture intersectionality, discussion, and collaboration across them.

I know many young self-defined feminist grad students, so the perspective is there. But I see several difficulties with feminist media studies today. First, I think postfeminism was a tremendous distraction that drew attention away from deeper issues. Second, women’s studies more broadly seems to have made a conscious (and appropriate) choice to move from second-wave (white, upper middle class) perspectives to third-wave (developing world, attention to race and ethnicity), so feminist media studies seems either in the past or failing to account for broader shifts. Third, our methods needs updating and/or radical reconceptualization. I don’t believe that queer theory has replaced feminist theory, but it must be accounted for–in particular for how it had pushed past or complicated the initial questions posed by feminist theory. There is good work yet to be done, but I think it will look different.

These are excellent points; thank you for your comments. These are all important issues. Some of these scholarly dilemmas, I feel, are actually beginning to be tackled in current scholarship. But perhaps it’s also a matter of whether graduate students have come to feel so turned off of scholarship deemed feminist, that they’re also not gravitating toward it. Considering that graduate students are the feminist scholars of today and tomorrow, it seems we need to raise this conversation, as several commenters have noted, to support their work in this regard.

Mary (and commenters),

Thanks for an important and compelling discussion! At SCMS this year, the folks who are working together to revive the Women’s Caucus discussed frustration with the tendency at most conferences to have one or two special panels that focus on gender (or race, sexuality, or class–pick one or all!), while the majority of panels at conferences carry on their work as if it has no impact on gender, etc. I think we’re definitely hitting up against the discourses of postfeminism, but I think we’re also still dealing with the treatment of the study of gender as “women’s work” (as if men, masculinity, or male-targeted texts are genderless). We have so many, many supportive, smart male colleagues who no doubt have our backs in terms of valuing the work we do, but I think we need them to see how our work reflects on theirs (and vice versa)–and press them to expand their analyses a bit.

I love the Hall quote Nina referenced above: Hall said that feminists broke in like a thief in the night and crapped on the table of cultural studies…his words definitely suggest the rupture and the aggression felt by the predominantly male scholars at the CCCS in the 1970s. As lovely as the metaphor is, I think we’ve (or maybe I’ve) gotten to a place, especially since feminist media studies has made a real impact on our field, that we/I don’t want to be seen as “those women/that woman” who are constantly bringing up gender, race, sexuality, etc. in Q&A sessions when we feel important aspects have been left out of analyses.

All of this is to say that I think Mary’s on to something–something really important–and we need to be talking about how to revive media studies work on gender from a feminist perspective.

Great piece, Mary — thanks so much. I’m really sorry I missed Tara’s talk, though I’ve heard her sentiment expressed by others in the past few years.

I’m wondering if we might think about how the perceived dearth, absence, or marginalization of feminist media studies is subject specific. For example, the majority of my work has been within girls’ studies, a site of vibrant feminist media scholarship since the early 1990s.

Hi Mary,

I think this is a really thought-provoking post, and though I’m not a media scholar, I thought I’d mention something I thought of. A couple years back, I reviewed a pretty great collection of essays by Merri Lisa Johnson called Third Wave Feminism and Television (my review: http://www.rhizomes.net/issue17/reviews/chavez.html), that I think took up some of these same questions about the relationship between media studies and feminism, and more specifically how television can be a source for feminist theory building. The impetus for that collection really seemed to be the sort of “predictable” findings of most feminist media studies, and so the essays in there all tried to do work to go against the grain of “predictable” feminist readings. While I challenge the notion of “predictability” a bit, I think that these essays were doing some important work to revitalize the feminist/media studies link. It might be worth checking it out.

Anyway, lots to think about here in relation to the politics of citation and also the continued influence of postfeminism…

Thanks for turning my attention to the blog.

Karma

I wonder how political projects and the academic call for original research gel or don’t gel to further contribute to the problems you note here, Mary. When a political project develops, younger scholars risk alienating themselves from senior scholars by toggling with that project too much, and yet if they fall in line with the project as it exists, they risk their work seeming to be derivative, unoriginal, and already-written. So there’s something of an institutional damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t bind, that perhaps makes it easier for younger scholars to gravitate towards other interests of theirs where it’s easier to assert one’s original take on things without angering a former wave of scholars too much.

Obviously, this issue replicates itself in many situations and sub-fields. And I don’t present it as a reason for why I personally haven’t done enough feminist scholarship (maybe I flatter myself as “supportive” and “smart”, but the final sentence of Melissa’s first par. above provides a sting of recognition). But I often hear feminist scholars of my generation who feel that the generation above them have been the hardest on their scholarship since it doesn’t “do” feminism in the same way, and yet they’d be bored to rewrite the same papers, or at least reiterate the same basic point albeit with a different case study. I use that example because many of these women and men have succeeded in spite of the challenge, so I don’t mean to suggest an impenetrable barrier, but it’s important for us to realize how hard it might be to do political project-related work in a pre-tenure environment.

Hope I’m not chiming in here too late, but several of these comments have led me to want to add to the conversation, in particular comments by Melissa, Jonathan, and Mary Kearney. First, in Melissa’s comments about supportive male colleagues who need to expand their analysis a bit, I agree. Indeed, when feminists raised issues of power and inclusion in late night political satire after reading the first edition of my book, I did expand the analysis in the second edition to include a discussion on those issues. Like Jonathan, I’m not sure it is enough or even sufficient, but it’s a start.

But I think Mary Kearney may also be hitting on an important point, echoed in others’ comments, and that is the way feminist scholarship may not be as expansive in subject areas as it should be (thereby getting caught up in “eddies” of certain areas–fandom, melodrama–but not being adequately applied in other areas. For instance, my research is in politics, public affairs, news, and talk shows. But I am hard pressed to tell you who is writing on Rachel Maddow, or who is writing on Katie Couric and Diane Sawyer as anchors, or who is writing on Sarah Silverman, Wanda Sykes, and Chelsea Handler. Now that may be my ignorance or stupidity (given), but I do try to keep up with scholarship in these areas, and no feminist names jump to mind. I’ve made the point many times before (as has Toby Miller, John Hartley, and Todd Gitlin), but American cultural studies has done a fine job of analyzing melodrama–how about some public affairs?

Which leads to my third point–in this day and age of Flow, Antenna, In Media Res, and personal blogs, feminist scholars may need to do a better job of marketing themselves through their writing in these more open and immediate forums. I now have the potential to know what graduate students from around the world are working on–something not so easy to know several years ago. So when I am contacted by the Houston Chronicle to comment on Chelsea Lately, I should be able to recommend that they speak with a feminist scholar as well as the male colleague to whom I directed them. And finally in terms of marketing oneself (and somewhat leading back to point one), when we were doing an anthology on HBO, two of our feminist colleagues wrote us and asked if they could add a chapter (beyond the one they were doing on Six Feet Under) on “What HBO Has Done for Women.” We thought it was a great idea, yet somewhat not fitting the format the book had taken, but we included it because it was important. But without that marketing/push, that was a feminist road we weren’t taking.

Anyway, thanks Mary for the conversation, and I hope these comments are helpful in some way.

Sadly late to this conversation as well. I’d second the comments of Greeny28. Postfeminism has been a massive distraction, or at least far too long a side trip, and I think as an area we’re really struggling to find the way forward–the next set of questions, the next theoretical refinement. Multiple applications are good, but at what point is it derivative (taking Jeff’s point though on the need to visit other genres and media spaces). It’s been really tough to theorize why and how some things exhibit feminist gains and others don’t. Feminist media studies seems very stalled to me. I think it is a matter of needing to dig deeper and figure out what are the bigger questions that need answered.

As alluded to in a number of the comments, I find myself using my feminism fairly often in the other aspects of my job these days. Not that it shouldn’t be in scholarship as well, but to make the point there are many fronts that require feminist engagement.

Just to play this out further (and as help with my thinking for an In Media Res post I am set to do soon :-), you say: “Multiple applications are good, but at what point is it derivative (taking Jeff’s point though on the need to visit other genres and media spaces)? It’s been really tough to theorize why and how some things exhibit feminist gains and others don’t.” But maybe these applications and extensions into other areas can help with your last sentence. For instance, I think this clip from The Daily Show exhibits well the way in which Fox News is engaged in the broader far right project of crafting public women in very particular (and safe and attractive) ways:

http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/tue-december-8-2009/gretchen-carlson-dumbs-down

The far-right can’t go completely backwards; feminist gains have been achieved in some respects. But they ARE damned and determined to fashion those gains in ways still conducive to patriarchy. My point is that by engaging other genres and media spaces, the connection to overt broader societal ideological efforts against feminism (ones that extend beyond media) might help illuminate those bigger questions that need answering, yet seem hidden by confinement to certain areas of media textuality.

Does that make sense?