Mad about Mad Men: Antenna takes a Look at AMC’s High Profile Drama

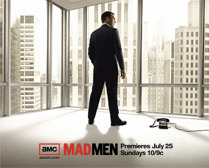

The first episode of season four of AMC drama Mad Men shows Don Draper, creative director extraordinaire, and his colleagues in a position strikingly similar to that of the show itself, trying to make a huge splash with something small in size. Don Draper, Roger Sterling, et al. have their fledgling new agency; and Mad Men has a show with a small audience and a huge footprint. The last few weeks I have felt that Mad Men was everywhere. First there was the 17 Emmy nominations (heavily advertised by AMC). Then I wandered into Banana Republic only to be met by large signs advertising its partnership with the show. Don Draper graced the cover of TV Guide at the checkout lane of my local grocery store. It was inescapable; even Inside Higher Ed featured an article about Mad Men’s historical context last week.

The first episode of season four of AMC drama Mad Men shows Don Draper, creative director extraordinaire, and his colleagues in a position strikingly similar to that of the show itself, trying to make a huge splash with something small in size. Don Draper, Roger Sterling, et al. have their fledgling new agency; and Mad Men has a show with a small audience and a huge footprint. The last few weeks I have felt that Mad Men was everywhere. First there was the 17 Emmy nominations (heavily advertised by AMC). Then I wandered into Banana Republic only to be met by large signs advertising its partnership with the show. Don Draper graced the cover of TV Guide at the checkout lane of my local grocery store. It was inescapable; even Inside Higher Ed featured an article about Mad Men’s historical context last week.

It took The Hollywood Reporter and Entertainment Weekly to help me realize I had fallen into a common trap, overestimating the show’s ubiquity. Recent articles have observed that Mad Men does not have spectacularly high ratings, with a regular viewership of only 1.9 million. Critically successful, the show has also garnered a good deal of interest from academics. Over the next few months Antenna will be featuring weekly the opinions of several media scholars who will comment on Mad Men’s fourth season as it unfolds. What makes a show on a network with extremely limited original programming and a viewership just under 2 million such a significant cultural event? Is it an issue of quality? content? the program’s relationship to the past? This series of articles will give our readers and contributors an opportunity to address these questions as well as many more issues involving the series.

For the record, I think the attention paid to Mad Men is well deserved. It always strikes me as not only a well written series but one that is extremely well crafted down to the music choices, lighting angles, and small gestures. It is a series that shows its work, the artistry that goes into a really good show. It is a series that captures a period of history and change complexly and with great pathos. But such nuance is not the whole story of Mad Men’s success.

Mad Men has succeeded in carving out its space in the culture by practicing what Don Draper preaches: good advertising. Entertainment Weekly and The Hollywood Reporter observed that amongst those 1.9 million viewers is a much higher percentage of viewers with incomes over $100,000 than comparable cable dramas. The series has parlayed this into a targeted, strategic marketing campaign. The Mad Men/Banana Republic match may be the most visible partnership, but the show’s marketing efforts are much more complex. Viewers of the first episode were treated to lengthy advertisements from the episode’s sponsor, BMW, featuring a real “Mad Man” discussing the company’s early advertising. The ads beautifully tied together the series’ content, the ads’ product, and its affluent viewers. For a full month, Mad Men prepped these viewers to get excited for the new season. Having once indicated that I ‘liked’ Mad Men on Facebook, I was treated to daily updates letting me know about AMC marathons of previous seasons, on-line programs letting me Mad Men myself or have a job interview for Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce, mix period-appropriate cocktails, listen to Mad Men radio on Pandora, or access DVD style extras after the first episode ended. The series has clearly committed itself to creating as many opportunities for immersion for its viewers as possible. This marketing approach, and its apparent success – Sunday’s premiere drew over 2.9 million! – focuses on the quality of viewer for advertisers and the quality of these viewers’ interactions with content.

Apparently the group at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce received this memo as season four begins with a recently separated Don Draper who has becoming increasingly impatient and committed to his vision for creative directors and the company. The season begins in turmoil. The new agency has had some success but is still at risk. Don’s house has been taken over by Betty and Henry, and Don is living in a small bachelor apartment. This episode, “Public Relations,” was an excellent balance of melancholy and hope. The storm clouds are overhead, but the episode ends with a wink that with the spark of genius evidenced by Don, Peggy, and the others in previous seasons, success is on the horizon. Whether Matthew Weiner and his team will have their own spark of genius in this new season is yet to be seen. We hope you will join us in discussing this season of Mad Men as we watch to find out.

Season 3 ended with the gender-integrated team opening a new agency, women on the verge of the second wave! Season 4 begins with Peggy’s inappropriate advertising stunt and, worse, her inability to chart a path through the agency’s decision-making process. Don’s cruel humiliation of Peggy is graciously accepted. I wonder what happened to Don’s respect for Peggy from Season 3 and her competence. Perhaps Peggy is a foil to demonstrate Don’s state of mind. Perhaps the show needs to re-establish the punishing crucible so that women’s progress can once again be measured and appreciated.

In an article in WSJ.com, Natasha Vargas-Cooper admonishes SCDP to get with the times: “If the men of Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce want to keep themselves attractive to clients looking for innovative strategies they may want to make more room on their masthead for Joey and Peggy — or at least give them a door to their office.” (27 July 2010).

Kyra notes in her Antenna posting that Mad Men has a relatively small viewership yet is intensely interesting in some quarters. WSJ.com will follow Man Men this season (blog/wsj.com/speakeasy). In their first posting (27 July 2010), the WSJ.com panel commented on the show’s historical verisimilitude about gender and agency practices and also its inevitable resonance with gendered work relations today.

Toril Moi observes,

“In its representations of gender ‘Mad Men’ appeals rather powerfully to our need or wish to feel superior to the 1960s. It encourages us to think that at least we have sorted out gender relations by now. But of course we haven’t. In the 1960s women suffered from the conflict between work and marriage (Joan’s leaving the agency when she got married is a good example), today the conflict is between work and small children. Women are still caught out in this bind far more often than men. The glass ceiling still exists. So ‘Mad Men,’ much as I admire the series, may be contributing to a far too upbeat assessment of gender relations in our own era. On the other hand I actually think it is true that women have a better deal in work life today than in the 1960s, and I don’t want to blame ‘Mad Men’ for bringing this out.”

For all my annoyance with Don’s humiliation of Peggy, Mad Men remains on the cusp of the past and the present, inviting us to explore continuities and changes in women’s condition.