Of Pigs and BullSh*t: Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FCC

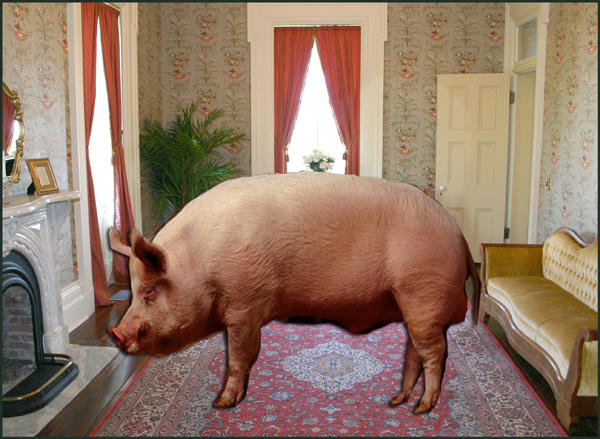

The narrowly decided 1978 Pacifica decision was, from one perspective, a battle over pig metaphors. The majority decision, penned by Justice Stevens, sanctioned the FCC’s indecency policy on the ground that the broadcast medium was “uniquely pervasive”; therefore it was permissible to restrict broadcasters from airing indecent content during the hours when children were most likely to be in the audience. In Pacifica, indecent content was not being forbidden, just “rezoned” to a time when kids were less likely to be exposed to it. Likening the policy to public nuisance laws, the Court reasoned that it “may be merely the right thing in the wrong place, — like a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.” In his strongly worded dissent, Justice Brennan drew on another pig metaphor, this one derived from a 1957 indecency case, in which he claimed that the policy endorsed by the majority was like burning “the house down to roast the pig,” a far too excessive response that could have dire consequences for free speech.

The narrowly decided 1978 Pacifica decision was, from one perspective, a battle over pig metaphors. The majority decision, penned by Justice Stevens, sanctioned the FCC’s indecency policy on the ground that the broadcast medium was “uniquely pervasive”; therefore it was permissible to restrict broadcasters from airing indecent content during the hours when children were most likely to be in the audience. In Pacifica, indecent content was not being forbidden, just “rezoned” to a time when kids were less likely to be exposed to it. Likening the policy to public nuisance laws, the Court reasoned that it “may be merely the right thing in the wrong place, — like a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.” In his strongly worded dissent, Justice Brennan drew on another pig metaphor, this one derived from a 1957 indecency case, in which he claimed that the policy endorsed by the majority was like burning “the house down to roast the pig,” a far too excessive response that could have dire consequences for free speech.

Sadly, there are no new pig metaphors in Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FCC, the July 13 appellate court decision that ruled the FCC’s indecency policy to be unconstitutional, though the Pacifica case looms large in the decision. The latest in a series of decisions over the Commission’s indecency enforcement, the Fox court argued that the FCC’s indecency policy was “impermissibly vague,” had a dangerous chilling effect on speech, and violated the First Amendment. According to the court, the current policy had produced too much uncertainty as to what was or was not indecent and thus encouraged broadcasters to adopt overly cautious practices of self-censorship to avoid Commission penalties.

Though the court acknowledged it lacked the authority to overturn the Pacifica precedent, it indicated that the “uniquely pervasive” rationale at its center seemed like something of a relic, an anachronism in an era of online video, the expansion of cable television, social networking sites, or of technologies like the v-chip that allow parents to block the very content the indecency rules were designed to shield from children. Though this was not the meat of the court’s decision, it has been the part of the Fox case that has received a good deal of praise and attention. Commentators ranging from the New York Times editorial board to former FCC chair Michael Powell have suggested that Fox reinforces a marketplace approach to media regulation, one that interprets all content restrictions as outdated, unconstitutional, and unnecessary in a world of media plenty. With so many potential pigs in the parlor, to treat broadcasting as uniquely pervasive no longer seemed tenable.

Yet to me this is the wrong takeaway from Fox. The appellate court did not only gesture to how the majority decision in Pacifica may no longer be salient, but also importantly implied that the view offered in Brennan’s dissent was perhaps right after all. The crux of the Fox decision hinged on the vagueness of the Commission’s indecency rules, which had lead to contradictory and discriminatory outcomes. How does it make sense, the court wondered, that the Commission deemed the word “bullshit” patently offensive, but not “dickhead”? Perhaps more importantly, why were expletives permissible when uttered by the fictional characters in Saving Private Ryan, understood as necessary to the verisimilitude of the film, but not when spoken by actual musicians interviewed for the documentary The Blues? Such inconsistencies, the court surmised, potentially reflect the biases of the commissioners themselves and “it is not hard to speculate that the FCC was simply more comfortable with the themes in ‘Saving Private Ryan,’ a mainstream movie with a familiar cultural milieu, than it was with ‘The Blues,’ which largely profiled an outsider genre of musical experience.”

The vagueness of the rules, in other words, not only made it very difficult for broadcasters to anticipate when and whether the use of terms like “douchebag” (my example, not the court’s) would be ruled indecent, but provided latitude for the Commission to privilege its own mores and values in determining what should be permissible in the public sphere. It is a view that echoed Justice Brennan’s dissent in Pacifica, in which he warned that that the majority decision would sanction the “dominant culture’s efforts to force those groups who do not share its mores to conform to its way of thinking, acting, and speaking,” and in which he accused his colleagues of an “ethnocentric myopia,” the Pacifica decision itself an imposition of the justices’ own “fragile sensibilities” on a culturally pluralistic society.

Brennan’s concern was not that the Commission’s and the Court’s indecency policy was imprecise, but that its intent seemed all too transparent, as a way to silence speech that offended their sense of decorum, expose taboos they’d prefer to remain hidden, articulate political and social values they find unpalatable. Not only were they burning the house to roast the pig, but the distinctions they were to draw between pearls and swine would sanction their own presumptions about aesthetics, ethics, and respectability.

And this I think is Fox’s important referendum on Pacifica and the indecency policy it had sanctioned: not that the media marketplace is now a panacea of free speech, but that broadcasting policy too often can operate as a cudgel to privilege the sensibilities and perspectives of particular sectors of the community over others in the guise of seemingly neutral regulations. It’s not, in other words, that our contemporary parlors are overrun with pigs, but that to many of us those pigs in the parlor may never have been pigs after all.

I learned a lot from this post–thank you for the historical context.