The Flying Frenchman: Édouard Carpentier, 1926-2010

While growing up in suburban Montreal, my British grandmother often told me stories about “real” wrestling in Québec during the 1960s, not that she was ever a fan. In these stories, she was merely recalling with pride the stars admired by my late grandfather after they had emigrated to Canada. Among them was Édouard Carpentier—“a real athlete,” she’d boast—who passed away this past Saturday, October 30th, at the age of 84. “He was a real wrestler,” she repeated with almost nauseating frequency. But while the idea irked me at the time because I thought she was taking a shot at the wrestlers I loved—“Macho Man” Randy Savage, “The Model” Rick Martel, “Mr. Perfect” Curt Hennig, among others—I never quite managed to fully doubt her. Maybe wrestling was real at one time, and maybe Carpentier was a star.

Media scholars have two reasons to remember Carpentier. He came into his own during wrestling’s transition to an entertainment industry led by three companies, known as “the Big Three,” each taking advantage of the medium of television in its own ways. He was also featured in a wonderful Québécois documentary film, La Lutte/ Wrestling (1961), made by Michel Brault during the cinéma direct era with consultation by Roland Barthes.

Born Édouard Ignacz Weiczorkiewicz to a Russian father and Polish mother in Roanne, Loire, France on 16 July 1926, Carpentier became a member of the French Resistance during the Occupation, for which he was awarded two medals by the French government. He moved to Canada in 1956, becoming one of the biggest stars in North America.

His career highlight came in 1957, when at the age of 26 he wrested the NWA World Heavyweight championship from Lou Thesz, one of the greatest wrestlers in the history of the industry. The title win was not without controversy. This was a period when the wrestling industry consisted of regional firms, or “territories.” The National Wrestling Alliance, or NWA, was formed by several regional promoters in 1948, and was henceforth regarded as a national governing body in the U.S. One world champion was crowned, the second being Thesz himself. The title would only change hands via a vote among the promoters. On 14 June 1957 in Chicago, Carpentier got the nod, in a way. He faced champion Thesz in a best-of-three battle. The wrestlers split the first two falls, with Carpentier winning the third on a disqualification. Titles then as now only change on a pinfall or submission. Still, the official raised Carpentier’s hand in victory and awarded him the title.

A complex storyline was supposed to follow, where Carpentier and Thesz would each claim rights to the title. Instead, a legitimate controversy was stirred. Carpentier left the NWA to help launch the upstart AWA (American Wrestling Association), which then competed with the NWA for dominance in American wrestling.

Carpentier would never win another world crown, but he was a crucial player as the industry was slowly revolutionized—over the next 40 years trading in dark, smoke-filled arenas for broadcast television and later pay-per-view and cable, all of which made it a billion-dollar, international business. He was also an accomplished trainer, serving as mentor to some of wrestling’s biggest names, including André the Giant, a key player in the 1980s boom period in the WWF (World Wrestling Federation).

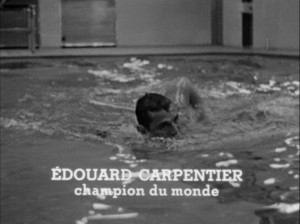

A mere 5’ 9 ½” tall and weighing in at 220 lbs., Carpentier would be considered a light heavyweight by current standards. But his athleticism was that of a gymnast, which promoters were eager to market as wrestling focused more on showmanship and less on legitimate grappling. Michel Brault captures this aspect of his appeal in La Lutte, where Carpentier makes a grand entrance by completing a flawless somersault dive into a pool during a workout session. He’s the only wrestler in the film who gets a title card.

Shot in Montreal’s legendary Forum, Brault’s documentary is as much about fan reaction as it is about the wrestling action. Still, it shows Carpentier at his best, with his trademark smile (and cauliflower ears!) as he greets an admiring fan on his way to the ring for a match.

On this occasion, Carpentier teamed with Dominic DeNucci to face the dreaded combination of the Fabulous Kangaroos, who, late in the bout, clasp on Carpentier a vicious clawhold.

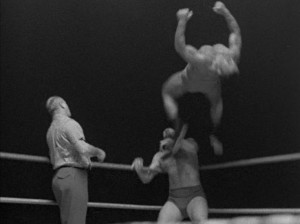

Battling back, Carpentier pounds his opponent into a corner, and then in an amazing move—one that, 50 years later, modern stars like Shawn Michaels would claim as their own—…

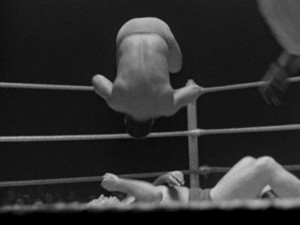

…completes a clean back flip from the top rope into the ring, landing squarely on his feet. In the closing moments of the bout, Carpentier gets set….

…. and executes a mid-air somersault, landing on his hapless foe with a textbook senton back splash to earn the pinfall.

A pioneering high flyer, a Montreal institution, a trainer of the next generation and a classy entertainer who became a bankable star in an industry gaining greater exposure through various media.

A real wrestler? It’s not difficult to see why my grandmother believed it.

Thanks for this great remembrance. Your piece and Lindsay’s on Lebron James make for a nice pair of investigations into mediated constructions of sports stardom. This is a fascinating glimpse into the professional wrestling world as it begins to move further and further into the showmanship that accompanies its transformation into a mass media institution.

This may be a stretch, but the fact that Carpentier lived to the age of 84 also seems to contribute to the notion that he was a “real athlete.” Considering recent discussions surrounding the early deaths of professional wrestlers, and how these deaths may be tied to the use of steroids and other drugs, perhaps his relative longevity is another signifier of his “authentic” physical acumen?

Great piece, Colin. I’m curious: How novel did the industry and fans consider Carpentier’s acrobatic style during the period you describe, and how was the style constructed as similar or dissimilar to more traditional, mat-based wrestling?