Late to the Party: Dirty Dancing

“Nobody puts Baby in a corner.” For years people have been quoting that line at me, so the only thing I knew about Dirty Dancing was that at some point someone would express defiance. Actually, I had sort of confused Dirty Dancing with another movie I’d never seen, Footloose, so I expected it to be about an uptight moralist preventing kids from dancing to the devil’s music. Oops. I was pleasantly surprised when it was more Karate Kid in the Catskills than another defense of the Twist.

“Nobody puts Baby in a corner.” For years people have been quoting that line at me, so the only thing I knew about Dirty Dancing was that at some point someone would express defiance. Actually, I had sort of confused Dirty Dancing with another movie I’d never seen, Footloose, so I expected it to be about an uptight moralist preventing kids from dancing to the devil’s music. Oops. I was pleasantly surprised when it was more Karate Kid in the Catskills than another defense of the Twist.

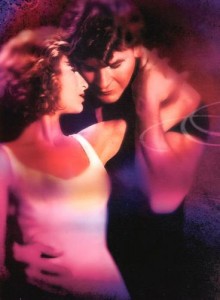

So what was it like to watch Dirty Dancing two decades after most everyone I know? Well, with a title like that, it was bound to either be more dirty or less dirty than I expected–turns out it was slightly more dirty, which is to say that I hadn’t quite anticipated the pelvic grinding of the titular dancing nor the constant beefcake of a shirtless Patrick Swayze. For what it’s worth, I now understand the outpouring of affection at Swayze’s death, the strangely sexualized nostalgia for someone I had always dismissed as an inoffensive B-lister.

What I wasn’t prepared for was the explicit class struggle that saturated the film, and it made me realize again how much of 1980s cinema overtly thematized class conflict and/or class mobility. Was it that, in the early days of neoliberal ascendancy, Hollywood still had the stomach to talk frankly about class? I won’t provide the whole long list of ’80s movies in this category, from 9 to 5 to Trading Places to Pretty Woman, but is it cultural near-sightedness to think that the film industry has mostly dropped the Reagan-era class consciousness?

Be that as it may, in this iteration, the cultural work of the film is to disarticulate working-class masculinity from the threat of moral subversion. Baby may be the protagonist, but Johnny Castle is the hero, and his achievement is to convince the bourgeoisie that he’s no less moral than the Ivy League kid. This lesson both never goes out of style and yet has curiously waned, such that Johnny as a character–the blue-collar man of gritty integrity and perfect pectorals–now looks and feels as dated as the Springsteen of Born in the USA. (I love Castle’s name, by the way: evoking both the dancing legends Vernon and Irene Castle and the markers of aristocracy that Johnny will never enjoy.)

When the famous line finally appeared, I was disappointed that Johnny, not Baby, actually delivered it; he, not she, ensures that Baby will remain uncornered when all is said and done. After everything she had gone through to claim her own destiny, validate her own judgment, and pursue her own pleasures in the film, it felt wrong that she didn’t get to formally declare her own independence. Thus the one moment I had been anticipating was a bit of a letdown.

Nonetheless, I enjoyed the scenes (implausible, but so what?) of Baby turning into a passable dancer in less than a week. And though it doesn’t take much to make me cry in movies, I teared up when she nailed the lift at the end. Another highlight: Jerry Orbach’s subtle performance as a basically good-hearted dad trying to make sense of a-changin’ times. Overall the movie holds up as an emotionally satisfying experience.

What doesn’t hold up is the atrocious decision to adulterate that wonderful early ’60s soundtrack with the lamest of ’80s pop. Why the hell is Eric Carmen, an artist unfit to mop up Otis Redding’s flop sweat, imposing himself on my Camelot-era resort? And I don’t care that “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” won, appallingly, both an Oscar and a Grammy–it’s a boring song that has no business being in the same multiplex, much less the same film, as the Ronettes (and I say that as a Jennifer Warnes fan).

Cringeworthy musical cues aside, the film retains its ability to please, and Jennifer Grey holds her own against the star power–I see it now–of Swayze. And at a time when even the so-called liberals in power refuse to launch a serious critique of class privilege–and the prospects for the Johnny Castles of the world have only continued to decline–the film’s blunt treatment of social inequality was refreshing. Finally, I hope there will always be a place in our culture for films that celebrate dancing: as something joyful, as something liberating, and as something always at least a little bit dirty.

Great take on this one, Bill. I think you’re dead on about class conflict as an almost default feature of studio pics in the eighties, vs. being practically nonexistent today. In addition to the films you mentioned, I’ll point out Pretty In Pink and Some Kind of Wonderful for exploring this theme again in the teen milieu. Hell, even the Rambo franchise starts off with an edge of class conflict!

I’m teaching an eighties film and TV class this summer, and I’d already planned on mining this angle a bit, but now I might just add Dirty Dancing to the screenings!